The Testimony of Bob Brown

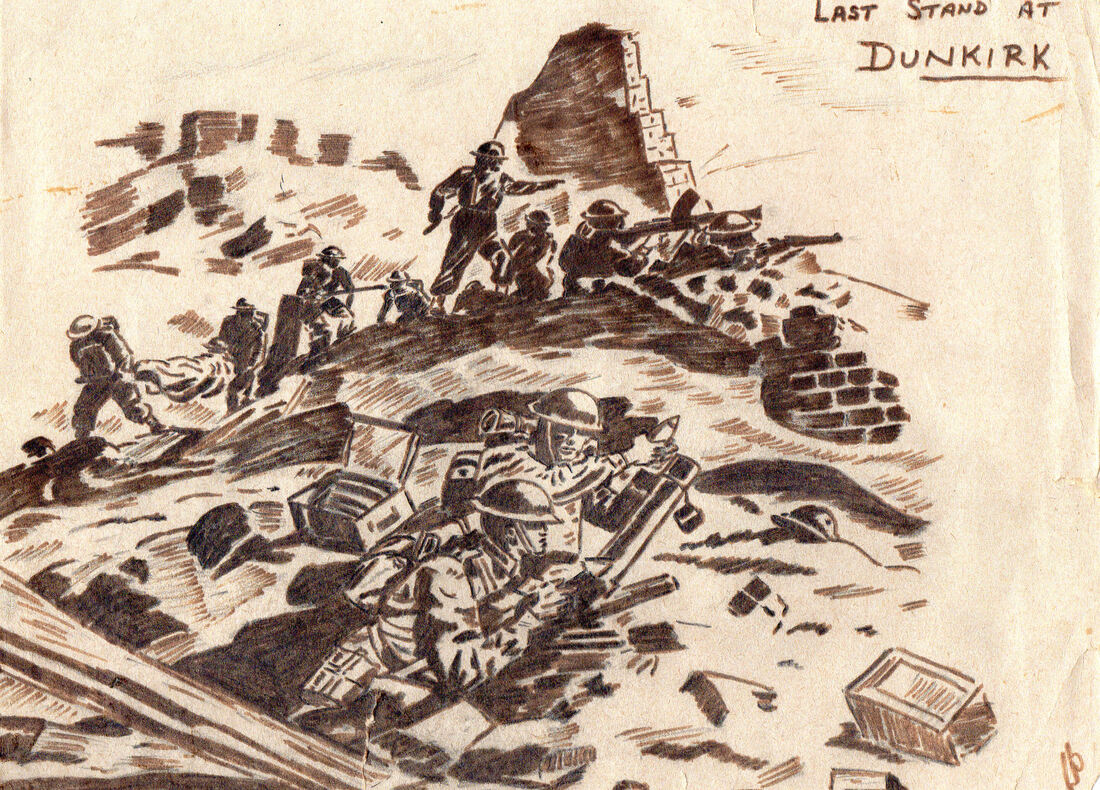

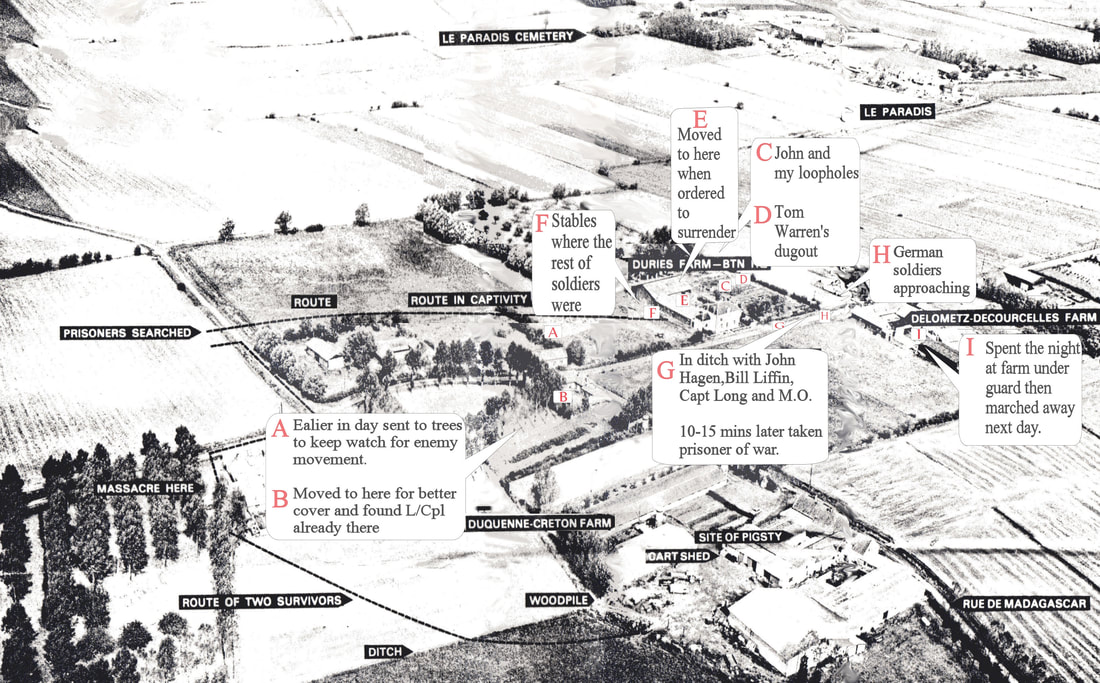

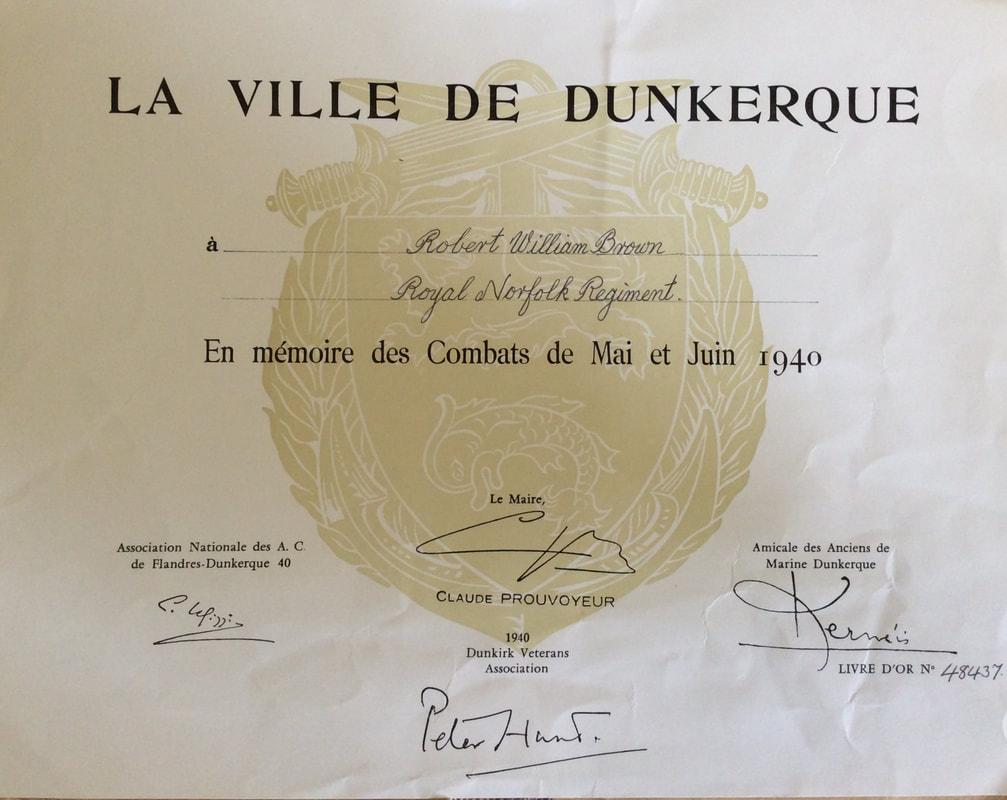

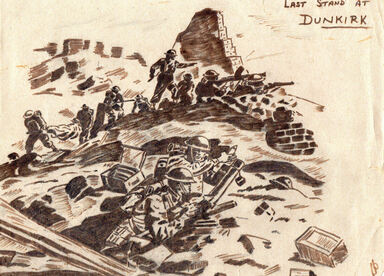

Bob Brown was a member of the Royal Norfolk Regiment who was present at Le Paradis on the fateful day. Whilst not a victim of the massacre, Bob has written and produced artwork about the event and his lucky escape when he took a different path to many others. We start with Bob's own drawing of the "Last Stand at Dunkirk" and then follow with a map underlining what happened to him at Le Paradis. We then continue with Bob's own words describing the situation at Le Paradis. We are extremely grateful to Bob and his family for permission to reproduce the images and drawings on this page.

See the bottom of this page for John Head's evaluation and comments on Bob's original artwork.

OUR Battalion HQ was Duries(z) Farm on the outskirts of Le Paradis. The date was 25th May, 1940. B company was on the right and on their right was the 1st Battalion Royal Scots. B company was defending the bridge and the village of Petit Cornet Malo. On the left of B company was A company, then D company, C company and the Scottish Fusiliers. The battalion front was 5,000 metres long and all the companies were by now very low in numbers, and this left no reserve.

All day and that night the enemy tried to cross the canal and we were losing quite a few men killed and wounded. The German losses were also mounting up but they must have outnumbered us by about five or six to one.

All day on the 26th was the same but apart from a small party of the enemy getting into the woods between B company and the Royal Scots, the line was held. About 2 o'clock in the morning of the 27th, a hot meal was brought up to us by Sgt Gilding who was acting company sergeant.

It was fairly quiet until 3.30 a.m, then they opened up with artillery and mortars and attacked in force. I was on the switchboard in the signal office in the cellar of the house and messages soon began pouring in to say all companies were fighting desperately. B Company was fighting hand to hand for every house and building in the village and they were the first to be overrun and out of touch with Bn HQ.

Soon all available men at Bn HQ were ordered out to take up defensive positions. I handed over the switchboard to "Porky" Ward who was on the radio to Brigade. The Adjt, Captain Long, sent me forward to a line of trees and told me to give him advanced warning of the enemy coming between the forward companies and Bn HQ. I was there for quite some time and then moved back a bit to some buildings at the crossroads which was more secure.

There I found L Cpl Garner of the Regimental Police and it made me feel better to be with someone else. He went and looked through a door towards Bn HQ, then called me over and pointed to a German motor cycle and sidecar, fitted with a machine gun and coming from behind us.

We quickly lined-up our rifles. He said: "You take the one in the side car and I'll take the one on the bike." We both fired together and the bike ran into the ditch. Our next move was to get back to the farm and let them know the enemy was behind them. The opposite side of the road was an estaminet with the door open. So, running faster than I had for some time, we dashed across the road and got inside safely. It was easy to crawl along the hedge and when we passed the bike in the ditch we could see they were both dead.

I reported to the Adjt and he told me to take up a position in the barn. The barn was made of galvanised iron riddled with bullet and shrapnel holes. I knocked a hole through the back then, getting a bale of straw, rested my elbows on it in a good firing position.

Mortar bombs were coming over and landing in the open space between the house and the barn. One exploded and caused several casualties and I thought I was hit, but it was only stones and rubble thrown into the farm. John Hagen was next to me and said: "Come on we'll find somewhere safer than this." At the end of the barn was a small brick shed with a tile roof so we went in there and knocked bricks out to make loopholes.

Whenever we saw the enemy creeping along the ditches or dodging behind a hedge we opened fire. They dropped from sight but that didn't mean they were hit as a near miss made you get down. Bill (not O'Callaghan?) was in a weapon pit in front of the barn with a Bren Gun. When he fired on automatic the Germans threw over more mortars bombs, so we shouted to him to fire single shots only. All through the day we were attacked and the house was hit several times until it was on fire.

The wounded were brought up from the cellar and laid where we could find a safe place. Dick Priest was one of them, hit in the leg. When I gave him a fag he said: "Don't let the Jerries get me Bob." I told him I wouldn't let that happen, but as things turned out there was nothing we could do about it.

His grave is in the cemetery at Le Paradis. Charlie High was using the same range finder to take the range where the mortar was firing from when he suddenly spun round and fell to the ground, hit in the shoulder. When he got up he was most annoyed and said so in a soldierly manner. This was now the middle of the afternoon. CSM Whitlam came round with the rum jar and said: "We might as well have this before the Jerries get it." I had nearly half a mug and couldn't see for a while as the water streamed out of my eyes.

Tom Warren was in a slit trench to the right of me and every time he fired he said: "And another Redskin bit the dust." I called to him and asked him if he was cutting a notch in his rifle butt and he replied: "Yes but there's not much room left now." Morale was very high and there was no thought of the outcome. Fred Clear and a few others that were left of A Company got through to us and took up a position along a wall after putting up bales of straw behind them to stop the blast of bombs and shells.

Sgt Wood went through the door onto the road and heard a motor bike, thinking it was our DR (dispatch rider) coming back, but it was a German. He drew a revolver and killed our sergeant before he could move.

As late afternoon was approaching things were getting desperate, men were getting killed and wounded and the ammunition was almost finished. The CO Maj Ryder got onto Brigade by radio and told them the position but he was told to hold on as long as possible and after dark make his way north. After another two hours there was no hope of lasting until dark as at the end of May we didn't get dark until late. The CO now made the decision to cease fighting and said that if any man thought he had a chance of getting away he could do so.

Bill, John and myself thought that if we kept in the smoke from the burning house we might make it. We went out of the side door into a ditch beside the road. The remainder went out of the cowshed door onto the field. At first they were met by a hail of bullets. Then at the second attempt the Germans came rushing out shouting. They were knocked about by rifle butts and kicks, then taken across to some more buildings and searched.

After a while they were marched across a road to a farm and, as they marched alongside a building, two machine guns opened fire and mowed them down. The Germans then went along and shot anybody that moved. By a stroke of luck Bert Pooley and Bill O'Callaghan, although wounded, survived underneath and eventually crawled away. Their story can be read in "The Vengeance of Private Pooley."

When we dropped into the ditch we found Adjt and the MO were there. Peering over the top of the ditch ready to get away, we found we were too late, the enemy was already coming up the road. John took aim with his rifle but the Adjt said "Don't fire Hagen." If he had they would have just opened up and killed us all. The MO (Lieutenant David Draffin - editor) got out first so they could see his Red Cross. There were loud shouts and cries of "Hande Hock." We helped the Adjt out as he was wounded and, not understanding German, put our hands up.

At this moment I could have cried. We had thought it possible to be wounded or killed but never taken prisoner. We were searched and marched down the road to their HQ and not badly treated apart from a few knocks and kicks. I had about 100 cigarettes in my pockets that Gordon Salmon our DR had brought back, and these they let me keep.

My wallet was full of photos of my family and they also let me keep them. That night we laid by the roadside, wounded included, and there was a thunder storm and we were soaked through. Next morning with nothing to eat we were marched away, carrying our wounded until they were put onto transport. That day we met Pedlar again, one of the five men left from D Company.

Also the same day we met Captain Gordon who had been taken in the village with the Royal Scots. I gave him a packet of Woodbines as he hadn't got a smoke. We were taken as far as Bethune and that night slept in the prison. The cells were crowded and the Germans used bayonets to get us up the stairs and inside.

Next morning, still without food, we marched away and during the day the French women ran out with bread and buckets of water. I remember one day sitting with my trousers round my ankles at the side of the road, when a French woman ran over and tucked a loaf of bread under my arm. All I could say was "Merci Madame."

Some nights we slept in fields and some nights in French barracks. There were so many of us that some were always outside. If we had not been so dazed there was a good chance we might have made our escape but we had no idea of what was happening or which way to go.

Eventually we were put onto a train, a French one with carriages, and that day Pedlar pinched the guard's ration so we had something to eat. We went through Luxemburg and into Germany. Trier was the first town and every window was hung with a Swatika Flag and I shall always remember John saying: "The curse of the Swastika."

We marched up the top of the hill to a camp, once more slept in the open and next day marched down again. Put into cattle trucks, as many as would go in, the doors were locked and we were on our way to somewhere in Germany.

All day and that night the enemy tried to cross the canal and we were losing quite a few men killed and wounded. The German losses were also mounting up but they must have outnumbered us by about five or six to one.

All day on the 26th was the same but apart from a small party of the enemy getting into the woods between B company and the Royal Scots, the line was held. About 2 o'clock in the morning of the 27th, a hot meal was brought up to us by Sgt Gilding who was acting company sergeant.

It was fairly quiet until 3.30 a.m, then they opened up with artillery and mortars and attacked in force. I was on the switchboard in the signal office in the cellar of the house and messages soon began pouring in to say all companies were fighting desperately. B Company was fighting hand to hand for every house and building in the village and they were the first to be overrun and out of touch with Bn HQ.

Soon all available men at Bn HQ were ordered out to take up defensive positions. I handed over the switchboard to "Porky" Ward who was on the radio to Brigade. The Adjt, Captain Long, sent me forward to a line of trees and told me to give him advanced warning of the enemy coming between the forward companies and Bn HQ. I was there for quite some time and then moved back a bit to some buildings at the crossroads which was more secure.

There I found L Cpl Garner of the Regimental Police and it made me feel better to be with someone else. He went and looked through a door towards Bn HQ, then called me over and pointed to a German motor cycle and sidecar, fitted with a machine gun and coming from behind us.

We quickly lined-up our rifles. He said: "You take the one in the side car and I'll take the one on the bike." We both fired together and the bike ran into the ditch. Our next move was to get back to the farm and let them know the enemy was behind them. The opposite side of the road was an estaminet with the door open. So, running faster than I had for some time, we dashed across the road and got inside safely. It was easy to crawl along the hedge and when we passed the bike in the ditch we could see they were both dead.

I reported to the Adjt and he told me to take up a position in the barn. The barn was made of galvanised iron riddled with bullet and shrapnel holes. I knocked a hole through the back then, getting a bale of straw, rested my elbows on it in a good firing position.

Mortar bombs were coming over and landing in the open space between the house and the barn. One exploded and caused several casualties and I thought I was hit, but it was only stones and rubble thrown into the farm. John Hagen was next to me and said: "Come on we'll find somewhere safer than this." At the end of the barn was a small brick shed with a tile roof so we went in there and knocked bricks out to make loopholes.

Whenever we saw the enemy creeping along the ditches or dodging behind a hedge we opened fire. They dropped from sight but that didn't mean they were hit as a near miss made you get down. Bill (not O'Callaghan?) was in a weapon pit in front of the barn with a Bren Gun. When he fired on automatic the Germans threw over more mortars bombs, so we shouted to him to fire single shots only. All through the day we were attacked and the house was hit several times until it was on fire.

The wounded were brought up from the cellar and laid where we could find a safe place. Dick Priest was one of them, hit in the leg. When I gave him a fag he said: "Don't let the Jerries get me Bob." I told him I wouldn't let that happen, but as things turned out there was nothing we could do about it.

His grave is in the cemetery at Le Paradis. Charlie High was using the same range finder to take the range where the mortar was firing from when he suddenly spun round and fell to the ground, hit in the shoulder. When he got up he was most annoyed and said so in a soldierly manner. This was now the middle of the afternoon. CSM Whitlam came round with the rum jar and said: "We might as well have this before the Jerries get it." I had nearly half a mug and couldn't see for a while as the water streamed out of my eyes.

Tom Warren was in a slit trench to the right of me and every time he fired he said: "And another Redskin bit the dust." I called to him and asked him if he was cutting a notch in his rifle butt and he replied: "Yes but there's not much room left now." Morale was very high and there was no thought of the outcome. Fred Clear and a few others that were left of A Company got through to us and took up a position along a wall after putting up bales of straw behind them to stop the blast of bombs and shells.

Sgt Wood went through the door onto the road and heard a motor bike, thinking it was our DR (dispatch rider) coming back, but it was a German. He drew a revolver and killed our sergeant before he could move.

As late afternoon was approaching things were getting desperate, men were getting killed and wounded and the ammunition was almost finished. The CO Maj Ryder got onto Brigade by radio and told them the position but he was told to hold on as long as possible and after dark make his way north. After another two hours there was no hope of lasting until dark as at the end of May we didn't get dark until late. The CO now made the decision to cease fighting and said that if any man thought he had a chance of getting away he could do so.

Bill, John and myself thought that if we kept in the smoke from the burning house we might make it. We went out of the side door into a ditch beside the road. The remainder went out of the cowshed door onto the field. At first they were met by a hail of bullets. Then at the second attempt the Germans came rushing out shouting. They were knocked about by rifle butts and kicks, then taken across to some more buildings and searched.

After a while they were marched across a road to a farm and, as they marched alongside a building, two machine guns opened fire and mowed them down. The Germans then went along and shot anybody that moved. By a stroke of luck Bert Pooley and Bill O'Callaghan, although wounded, survived underneath and eventually crawled away. Their story can be read in "The Vengeance of Private Pooley."

When we dropped into the ditch we found Adjt and the MO were there. Peering over the top of the ditch ready to get away, we found we were too late, the enemy was already coming up the road. John took aim with his rifle but the Adjt said "Don't fire Hagen." If he had they would have just opened up and killed us all. The MO (Lieutenant David Draffin - editor) got out first so they could see his Red Cross. There were loud shouts and cries of "Hande Hock." We helped the Adjt out as he was wounded and, not understanding German, put our hands up.

At this moment I could have cried. We had thought it possible to be wounded or killed but never taken prisoner. We were searched and marched down the road to their HQ and not badly treated apart from a few knocks and kicks. I had about 100 cigarettes in my pockets that Gordon Salmon our DR had brought back, and these they let me keep.

My wallet was full of photos of my family and they also let me keep them. That night we laid by the roadside, wounded included, and there was a thunder storm and we were soaked through. Next morning with nothing to eat we were marched away, carrying our wounded until they were put onto transport. That day we met Pedlar again, one of the five men left from D Company.

Also the same day we met Captain Gordon who had been taken in the village with the Royal Scots. I gave him a packet of Woodbines as he hadn't got a smoke. We were taken as far as Bethune and that night slept in the prison. The cells were crowded and the Germans used bayonets to get us up the stairs and inside.

Next morning, still without food, we marched away and during the day the French women ran out with bread and buckets of water. I remember one day sitting with my trousers round my ankles at the side of the road, when a French woman ran over and tucked a loaf of bread under my arm. All I could say was "Merci Madame."

Some nights we slept in fields and some nights in French barracks. There were so many of us that some were always outside. If we had not been so dazed there was a good chance we might have made our escape but we had no idea of what was happening or which way to go.

Eventually we were put onto a train, a French one with carriages, and that day Pedlar pinched the guard's ration so we had something to eat. We went through Luxemburg and into Germany. Trier was the first town and every window was hung with a Swatika Flag and I shall always remember John saying: "The curse of the Swastika."

We marched up the top of the hill to a camp, once more slept in the open and next day marched down again. Put into cattle trucks, as many as would go in, the doors were locked and we were on our way to somewhere in Germany.

In 1990 Bob Brown (pictured opposite in his army days) returned to the area to mark the 50th anniversary of the massacre. Bob made the following comments on a DVD to commemorate the anniversary.

"On May 10th when Germany invaded Belgium and Holland and France, we advanced into Belgium and took up positions we knew we were going to on the River Dyle. We dug in until the Germans came up to our positions but, after two or three days in this position, we had the orders to withdraw which we did back to another position.

We dug in again and then held on for another day or two and then the orders came to withdraw again. At this point we couldn't understand why we were withdrawing again because in every position we had we were holding them back, but we didn't know at that point that the Germans had broken through the Ardennes and were coming round into France behind our troops in Belgium. From then on it was a matter of taking these positions, holding them, and moving back until about the 21st May we were about on the outskirts of Tournai in Belgium on the River Escaut and there the action took place, there was heavy casualties there.

The action took place where Sgt Major Gristock won the VC in wiping out a machine gun post. And then we withdrew from there, the orders we got from there we were going to go back for re-inforcements and to be refitted, re-equipped. But we drew back Westwards and had to take a position on the Bassee Canal, where we were then in contact with the troops - the German troops that had come back through the Ardennes. And we were ordered to hold them as long as possible on the river position even if it meant to the last round and the last man to enable other troops to get through without being cut off towards the coast.

But at that time we didn't know that the evacuation was on, we thought they were just going back to the coast to take new positions and to hold them off again. And then it came up then to the 27th May and where we made our final stand here in this position at Le Paradis.

Standing here facing this direction there is a large building in front, the farmhouse called Duries(z) Farm. This was our battalion headquarters. It was surrounded in a square by buildings and a wall which we loopholed and made into a defensive position. After the Germans broke through the forward companies in this direction and we were then surrounded. This was the early hours of the morning and we held them off all day, from all the way round on all sides until late in the afternoon. About 5 O' Clock we were almost out of ammunition, the casualties were piling up very fast and our commanding officer Major Ryder then said rather than waste unnecessary loss of life - he took a vote about surrendering or carrying on.

Some said they would carry on, some said surrender and then he finished he gave the order "we will surrender" but if anybody thinks they can get away they are entirely free to do so - they are not deserting a sinking ship. And three of us together from the far end of the house went forward onto the road you see just down there on the left. We dropped into a ditch which happened to be very dry on the day, and when we wanted to cross the road to go further afield the German patrols were coming up the road and they just said hands up and we were taken prisoner. But the smoke from the burning building was blowing that way and that was the reason why we kept in that direction.

The men that surrendered and were massacred came out of the door of the building that was facing this direction. They were then marched round behind this farm, this building here. They were searched over the back of those trees to the left and then after they were searched, later they were marched up this small road that comes here. Marched up the small road and if anyone has had the book "The Vengeance of Private Pooley", they will find they had to halt there while a column of German troops came past.

They were then marched round to the right, to our left as we stand looking at it now to a farm building off the left hand side of the road. They were marched in front of the barn and two machine guns that were lined-up opened fire and just mowed them all down."

"On May 10th when Germany invaded Belgium and Holland and France, we advanced into Belgium and took up positions we knew we were going to on the River Dyle. We dug in until the Germans came up to our positions but, after two or three days in this position, we had the orders to withdraw which we did back to another position.

We dug in again and then held on for another day or two and then the orders came to withdraw again. At this point we couldn't understand why we were withdrawing again because in every position we had we were holding them back, but we didn't know at that point that the Germans had broken through the Ardennes and were coming round into France behind our troops in Belgium. From then on it was a matter of taking these positions, holding them, and moving back until about the 21st May we were about on the outskirts of Tournai in Belgium on the River Escaut and there the action took place, there was heavy casualties there.

The action took place where Sgt Major Gristock won the VC in wiping out a machine gun post. And then we withdrew from there, the orders we got from there we were going to go back for re-inforcements and to be refitted, re-equipped. But we drew back Westwards and had to take a position on the Bassee Canal, where we were then in contact with the troops - the German troops that had come back through the Ardennes. And we were ordered to hold them as long as possible on the river position even if it meant to the last round and the last man to enable other troops to get through without being cut off towards the coast.

But at that time we didn't know that the evacuation was on, we thought they were just going back to the coast to take new positions and to hold them off again. And then it came up then to the 27th May and where we made our final stand here in this position at Le Paradis.

Standing here facing this direction there is a large building in front, the farmhouse called Duries(z) Farm. This was our battalion headquarters. It was surrounded in a square by buildings and a wall which we loopholed and made into a defensive position. After the Germans broke through the forward companies in this direction and we were then surrounded. This was the early hours of the morning and we held them off all day, from all the way round on all sides until late in the afternoon. About 5 O' Clock we were almost out of ammunition, the casualties were piling up very fast and our commanding officer Major Ryder then said rather than waste unnecessary loss of life - he took a vote about surrendering or carrying on.

Some said they would carry on, some said surrender and then he finished he gave the order "we will surrender" but if anybody thinks they can get away they are entirely free to do so - they are not deserting a sinking ship. And three of us together from the far end of the house went forward onto the road you see just down there on the left. We dropped into a ditch which happened to be very dry on the day, and when we wanted to cross the road to go further afield the German patrols were coming up the road and they just said hands up and we were taken prisoner. But the smoke from the burning building was blowing that way and that was the reason why we kept in that direction.

The men that surrendered and were massacred came out of the door of the building that was facing this direction. They were then marched round behind this farm, this building here. They were searched over the back of those trees to the left and then after they were searched, later they were marched up this small road that comes here. Marched up the small road and if anyone has had the book "The Vengeance of Private Pooley", they will find they had to halt there while a column of German troops came past.

They were then marched round to the right, to our left as we stand looking at it now to a farm building off the left hand side of the road. They were marched in front of the barn and two machine guns that were lined-up opened fire and just mowed them all down."

Bob Brown is featured in Joshua Levine's book "Forgotten Voices Dunkirk" where he has the following to say about the massacre:

"We were told to take up positions on La Bassee Canal outside Bethune. We were told that we were fighting the Germans that had broken through the Ardennes and were coming round behind us. We had to hold them up as long as possible to stop them closing the gap and cutting off the BEF from the coast.

All four companies were involved. We were so depleted in numbers that we had to put everybody in defence, and we held them back until the early morning of 27 May when we were encountering our first tanks. There were also heavy mortars and artillery fire. Major Ryder - who was commanding officer by this time - ordered all surplus personnel out to the defence of battalion headquarters. So I handed over the switchboard to the wireless operator and I went out and I was told to go forward to a row of trees to let Captain Long know if I saw any Germans coming. I was there for some time and there was no sign of anybody. I withdrew about 100 yards to a farm where myself and a lance corporal kept watch. Suddenly we saw a German motorcycle combination with a machine gun mounted on it coming from behind us. Between the two of us we stopped it coming through and we had to get back to headquarters to let them know that the Germans were behind us. So we dashed across the road, crawled along the ditch, and gave the information that we had.

I then took up a position in a barn. We knocked holes through the walls which were, by this time, heavily riddled with shrapnel. Mortar bombs were dropping over the barn behind us. I was with a chap, John Hagan, who said: 'We'll find somewhere a bit more safe,' and we went to the end of the barn and saw a small brick outhouse. We went in and knocked bricks out for loopholes and that's where we continued our defence for the remainder of the day. The other side of the barn was stables and cow sheds and barns, and the men there had done the same as us inside, and knocked bricks out for loopholes - so we were more or less an all round defence.

Towards the end of the afternoon Major Ryder came round to us and said there was no way we could get away from where we were, and that ammunition was running very low and he was taking our opinions as to whether we should surrender or carry on fighting. Some said fight on, others said surrender. I said "let's carry on as we are!" Because the morale was so high I had no thought of being taken prisoner, or being killed or wounded. We were just firing and making a joke out of it, really. But eventually Major Ryder said that there was no point wasting human life, that we had held them up for three days which was a very good effort, that we couldn't hold them indefinitely, and that we should have to cease firing. But he said that if anybody thought they could get away, then we were entitled to do our own thing. We wouldn't be running away from the battalion - we would be trying to save ourselves.

Myself and two pals decided we would go out of the door onto the road in the opposite direction to the other men. The smoke from the burning house was going that way and we thought if we used the smoke as cover we had more chance of getting away. We jumped into a ditch at the side of the road and in it was an adjutant lying wounded with the medical officer. When we looked over the top, we could see German patrols were coming up from the village of Le Paradis. So we couldn't get across the road. They saw us and shouted to us to put our hands up - and that was that. We stood there with our hands up until they came up to us.

They had the SS Flash and the 'Deaths Head' badge on their helmets. They seemed far superior to the British troops at that time. They had equipment that we had never seen and they were all armed with automatic weapons. But they treated us as reasonable as you would treat an enemy - just the normal knocks and pushes and shouts. When we got to their headquarters, the wounded adjutant and the medical officer were taken into the officers' mess where they were under cover and we were left outside. That night, there was a terrific thunderstorm, and we were soaked through half of the night.

In the meantime, the men in the outbuildings and stables had gone out into the field - but they were fired on, so they came back. Then they went out again, waving a dirty white towel on a rifle. They surrendered, and they were the ones that were marched away - and massacred.

"We were told to take up positions on La Bassee Canal outside Bethune. We were told that we were fighting the Germans that had broken through the Ardennes and were coming round behind us. We had to hold them up as long as possible to stop them closing the gap and cutting off the BEF from the coast.

All four companies were involved. We were so depleted in numbers that we had to put everybody in defence, and we held them back until the early morning of 27 May when we were encountering our first tanks. There were also heavy mortars and artillery fire. Major Ryder - who was commanding officer by this time - ordered all surplus personnel out to the defence of battalion headquarters. So I handed over the switchboard to the wireless operator and I went out and I was told to go forward to a row of trees to let Captain Long know if I saw any Germans coming. I was there for some time and there was no sign of anybody. I withdrew about 100 yards to a farm where myself and a lance corporal kept watch. Suddenly we saw a German motorcycle combination with a machine gun mounted on it coming from behind us. Between the two of us we stopped it coming through and we had to get back to headquarters to let them know that the Germans were behind us. So we dashed across the road, crawled along the ditch, and gave the information that we had.

I then took up a position in a barn. We knocked holes through the walls which were, by this time, heavily riddled with shrapnel. Mortar bombs were dropping over the barn behind us. I was with a chap, John Hagan, who said: 'We'll find somewhere a bit more safe,' and we went to the end of the barn and saw a small brick outhouse. We went in and knocked bricks out for loopholes and that's where we continued our defence for the remainder of the day. The other side of the barn was stables and cow sheds and barns, and the men there had done the same as us inside, and knocked bricks out for loopholes - so we were more or less an all round defence.

Towards the end of the afternoon Major Ryder came round to us and said there was no way we could get away from where we were, and that ammunition was running very low and he was taking our opinions as to whether we should surrender or carry on fighting. Some said fight on, others said surrender. I said "let's carry on as we are!" Because the morale was so high I had no thought of being taken prisoner, or being killed or wounded. We were just firing and making a joke out of it, really. But eventually Major Ryder said that there was no point wasting human life, that we had held them up for three days which was a very good effort, that we couldn't hold them indefinitely, and that we should have to cease firing. But he said that if anybody thought they could get away, then we were entitled to do our own thing. We wouldn't be running away from the battalion - we would be trying to save ourselves.

Myself and two pals decided we would go out of the door onto the road in the opposite direction to the other men. The smoke from the burning house was going that way and we thought if we used the smoke as cover we had more chance of getting away. We jumped into a ditch at the side of the road and in it was an adjutant lying wounded with the medical officer. When we looked over the top, we could see German patrols were coming up from the village of Le Paradis. So we couldn't get across the road. They saw us and shouted to us to put our hands up - and that was that. We stood there with our hands up until they came up to us.

They had the SS Flash and the 'Deaths Head' badge on their helmets. They seemed far superior to the British troops at that time. They had equipment that we had never seen and they were all armed with automatic weapons. But they treated us as reasonable as you would treat an enemy - just the normal knocks and pushes and shouts. When we got to their headquarters, the wounded adjutant and the medical officer were taken into the officers' mess where they were under cover and we were left outside. That night, there was a terrific thunderstorm, and we were soaked through half of the night.

In the meantime, the men in the outbuildings and stables had gone out into the field - but they were fired on, so they came back. Then they went out again, waving a dirty white towel on a rifle. They surrendered, and they were the ones that were marched away - and massacred.

Bob Brown in the Media

Over the past number of years Bob has been featured extensively in various newspapers. On August 8th, 2017, the Eastern Daily Press included a feature on the lead-up to the evacuation of Dunkirk under the heading "Dunkirk The Norfolk Men Who Kept the Hope Alive."

The article states: "When the Germans recommenced their advance on May 27, Brown had his finger on the pulse of the Battalion: because he was the switchboard operator in the Duriez Farmhouse cellar, the messages from the front line companies reached him first before the calls were passed through to the officers in the farm’s kitchen overhead.

When B Company was about to be overrun, Alf Blake, its signalman, confided in Bob Brown: “I’m afraid we’re for it. Don’t forget me. We’ve had some good times together. I don’t know whether I’ll ever be seeing you again.” It was one of the last messages from B Company, and it was the last time Bob Brown ever heard Alf Blake speak. He must have been killed shortly afterwards, joining the many who did not survive for long enough to surrender. There was no time for Bob Brown to be sentimental. As soon as the line went dead, he shouted up the stairs to the officers in the kitchen: “The line to B Company’s been cut!’

Bob Brown reported later: ‘We realised the situation was pretty desperate. We saw Germans crawling up a ditch towards us until we fired at them. We had to tell one of my friends who was firing with a Bren gun to restrict his shooting to single shots since he was drawing enemy fire in our direction. When mortar bombs began to fall on the Farm, Dick Priest, was wounded at the top of his leg. I asked him if he was OK and gave him a cigarette. When the farmhouse caught fire, he was placed outside in the courtyard. “Don’t let the Germans get me,” he said. I replied: “I’ll do my best.”

Bob Brown remembers Major Ryder giving the option of surrendering: "‘We’ve held up the Germans for a long time. What do you think about surrendering?’ Brown replied: ‘We’re all right. Let’s carry on.” His comrades agreed. They did carry on for a while. But subsequently Ryder announced from the courtyard: ‘We have to surrender. Anyone who wants to can escape. And if you do, you won’t be accused of running away.’

As we have already learned, Bob Brown went out of a different exit and was arrested - something at the time that made him very sad:

‘I felt like crying when I was taken prisoner,’ Brown reported later. ‘I felt humiliated, and was very dazed.’

It was only much later that he found out what had happened to the men who had walked out of the outer door of the stables on the western side of the courtyard.

Bob Brown only found out about the massacre in 1948-9 when Knöchlein was in his turn arrested, convicted of murdering the British soldiers and hanged.

The article states: "When the Germans recommenced their advance on May 27, Brown had his finger on the pulse of the Battalion: because he was the switchboard operator in the Duriez Farmhouse cellar, the messages from the front line companies reached him first before the calls were passed through to the officers in the farm’s kitchen overhead.

When B Company was about to be overrun, Alf Blake, its signalman, confided in Bob Brown: “I’m afraid we’re for it. Don’t forget me. We’ve had some good times together. I don’t know whether I’ll ever be seeing you again.” It was one of the last messages from B Company, and it was the last time Bob Brown ever heard Alf Blake speak. He must have been killed shortly afterwards, joining the many who did not survive for long enough to surrender. There was no time for Bob Brown to be sentimental. As soon as the line went dead, he shouted up the stairs to the officers in the kitchen: “The line to B Company’s been cut!’

Bob Brown reported later: ‘We realised the situation was pretty desperate. We saw Germans crawling up a ditch towards us until we fired at them. We had to tell one of my friends who was firing with a Bren gun to restrict his shooting to single shots since he was drawing enemy fire in our direction. When mortar bombs began to fall on the Farm, Dick Priest, was wounded at the top of his leg. I asked him if he was OK and gave him a cigarette. When the farmhouse caught fire, he was placed outside in the courtyard. “Don’t let the Germans get me,” he said. I replied: “I’ll do my best.”

Bob Brown remembers Major Ryder giving the option of surrendering: "‘We’ve held up the Germans for a long time. What do you think about surrendering?’ Brown replied: ‘We’re all right. Let’s carry on.” His comrades agreed. They did carry on for a while. But subsequently Ryder announced from the courtyard: ‘We have to surrender. Anyone who wants to can escape. And if you do, you won’t be accused of running away.’

As we have already learned, Bob Brown went out of a different exit and was arrested - something at the time that made him very sad:

‘I felt like crying when I was taken prisoner,’ Brown reported later. ‘I felt humiliated, and was very dazed.’

It was only much later that he found out what had happened to the men who had walked out of the outer door of the stables on the western side of the courtyard.

Bob Brown only found out about the massacre in 1948-9 when Knöchlein was in his turn arrested, convicted of murdering the British soldiers and hanged.

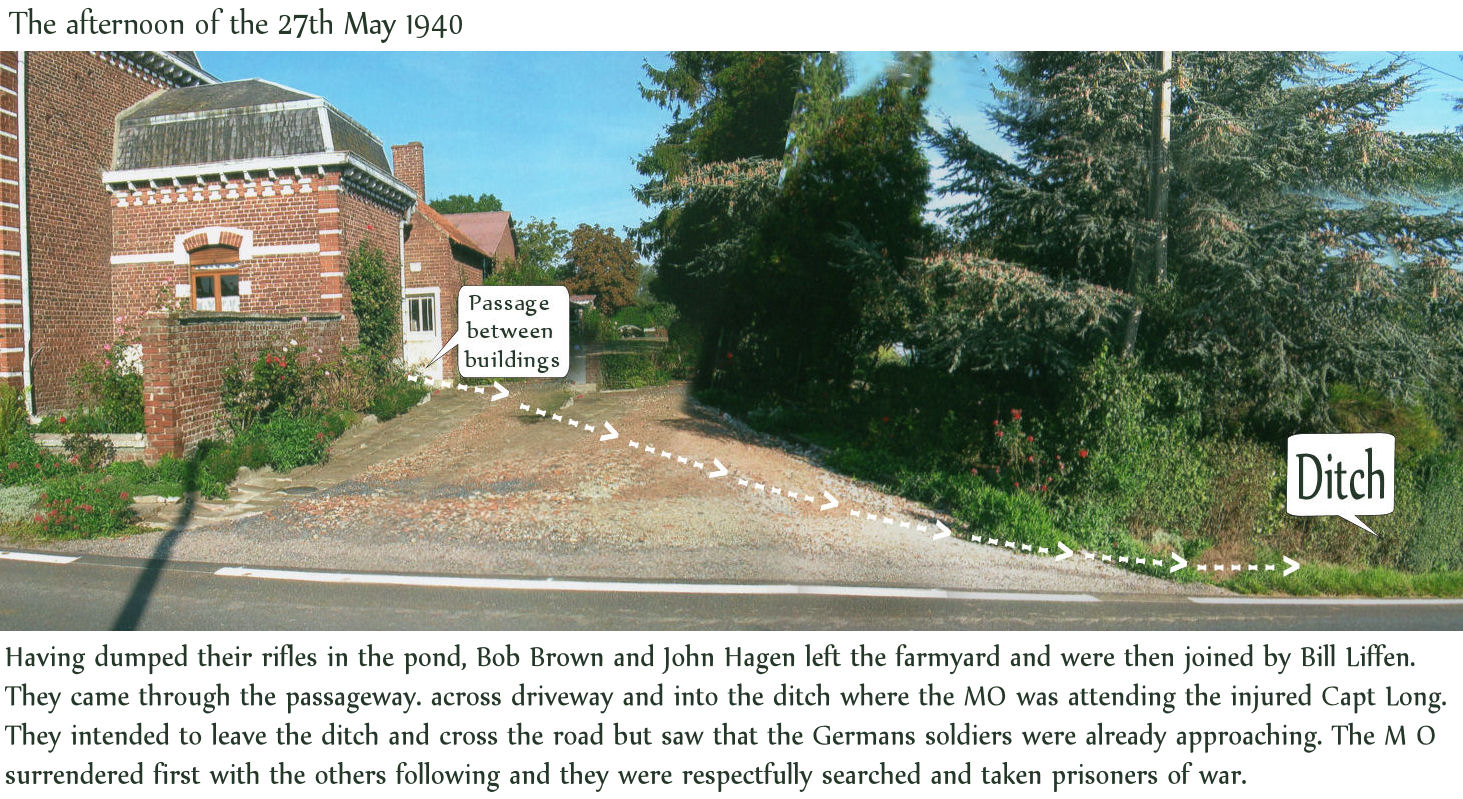

The Ditch Surrender

The route taken by Bob Brown from the farmhouse has been reconstructed by Bob and his daughter Vivienne Roberts and reproduced with their permission.

Escaping from the farmhouse several of the 2nd Battalion The Royal Norfolks dived into a ditch. Our photographs show the farm taken in the past few years with the ditch situated on the far right. Immediately above is a depiction of the route to the ditch taken by the soldiers and we are grateful to Bob Brown and his daughter Vivienne Roberts for their hard work in constructing this image and allowing us to use it.

Escaping from the farmhouse several of the 2nd Battalion The Royal Norfolks dived into a ditch. Our photographs show the farm taken in the past few years with the ditch situated on the far right. Immediately above is a depiction of the route to the ditch taken by the soldiers and we are grateful to Bob Brown and his daughter Vivienne Roberts for their hard work in constructing this image and allowing us to use it.

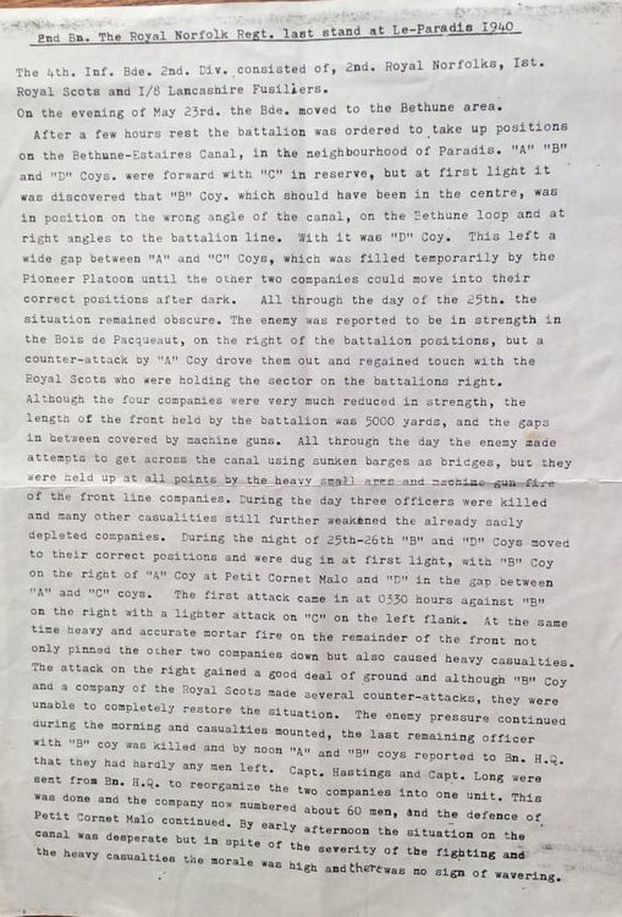

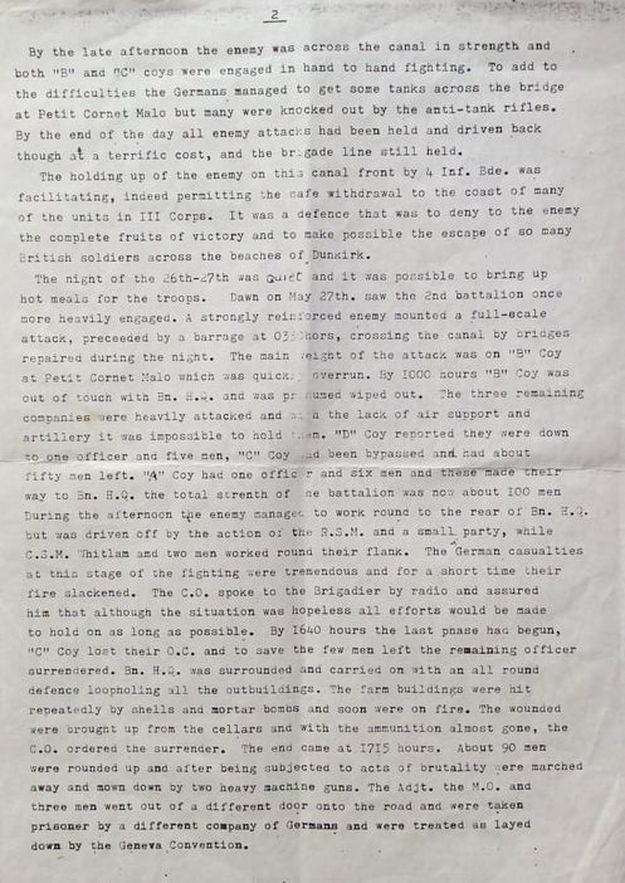

Below is a report written by Bob Brown and reproduced with the permission of his family. It is taken from Bob's collection of reports which also features a report written by Major Jimmy Howe which can be viewed by clicking here. Bob and Jimmy exchanged these reports on one of the pilgrimages to Le Paradis.

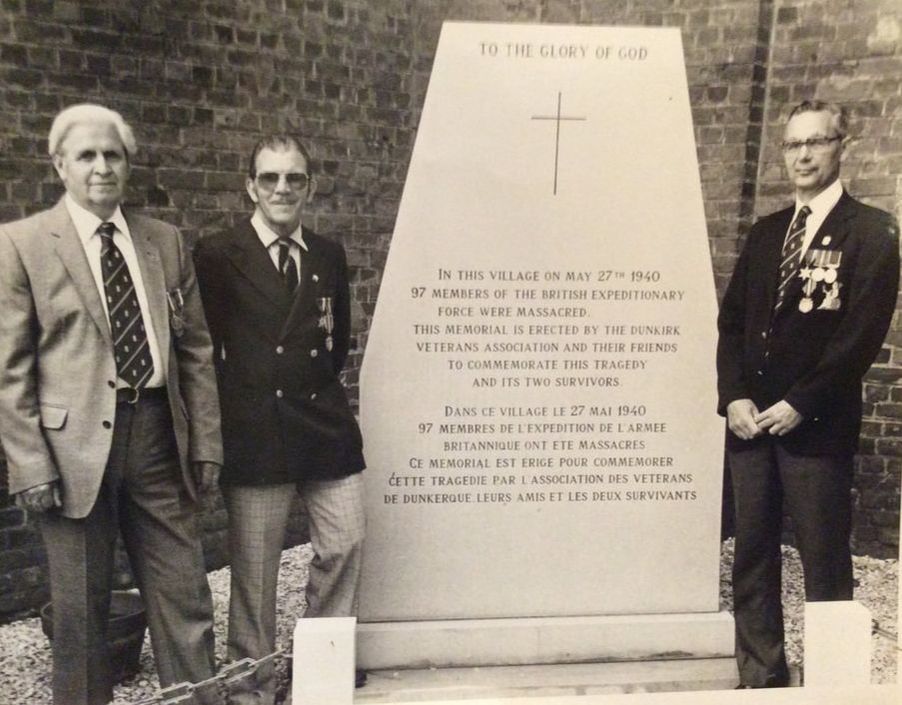

The photograph above is of Walter Lynes, "Pedlar" Palmer and Bob Brown in front of the memorial to the 97 at Le Paradis Church (photograph courtesy of Bob Brown).

We are grateful to Bob Brown and his daughter, Vivienne Roberts, for forwarding this ‘Memorial’ photograph to us together with their comments.

The photograph was taken at a later date from the unveiling of the Memorial in 1978. Pedlar’s real name was Horacio but he was also known as Ron.

Bob and ‘Pedlar’ met at the barracks when they joined up in 1938. They were both signallers and were together until the fighting in France when signallers were divided up and sent to different companies, Ron being sent to D company.

Vivienne knew ‘Pedlar’ as a child from the times when her dad (Bob) would take her to the Drill Hall. It was there Vivienne would practice the semaphore she had to learn in the Brownies on them.

Bob Brown didn’t know Walter, who lived in Swainsthorpe, until they met at the Dunkirk Veterans Association.

Bob Brown believed Brigadier Barclay was in favour of using the words' killed' or 'fallen in action' on the memorial but the general consensus was that the word 'massacre' was more appropriate.

We are grateful to Bob Brown and his daughter, Vivienne Roberts, for forwarding this ‘Memorial’ photograph to us together with their comments.

The photograph was taken at a later date from the unveiling of the Memorial in 1978. Pedlar’s real name was Horacio but he was also known as Ron.

Bob and ‘Pedlar’ met at the barracks when they joined up in 1938. They were both signallers and were together until the fighting in France when signallers were divided up and sent to different companies, Ron being sent to D company.

Vivienne knew ‘Pedlar’ as a child from the times when her dad (Bob) would take her to the Drill Hall. It was there Vivienne would practice the semaphore she had to learn in the Brownies on them.

Bob Brown didn’t know Walter, who lived in Swainsthorpe, until they met at the Dunkirk Veterans Association.

Bob Brown believed Brigadier Barclay was in favour of using the words' killed' or 'fallen in action' on the memorial but the general consensus was that the word 'massacre' was more appropriate.

Signaller Bob Brown’s Artwork ‘Last Strand at Dunkirk’ evaluated by John Head

Similar to Capt. Charles Long’s artwork, Bob Brown’s ‘Last Stand at Dunkirk’ reaches out beyond the drawing.

Bob was captured at Le Paradis which formed part of the valiant rear-guard defence that allowed the evacuation of Dunkirk to be successfully accomplished. Whilst not being at Dunkirk, Bob has allowed his experiences in battle, leading up to the surrender at Le Paradis, to be transposed to the Dunkirk beachhead.

With the clever use of shading Bob displays the intensity and the discipline of the B.E.F. which, whilst under constant attack, is stoic in its resistance. It is a scene of total defiance into which you are immediately drawn and placed alongside the mortar team in the foreground. You can feel the concentration that is required under frenzied conditions to ensure the range of the mortar on the identified target is correct. In the background the upright Officer/N.C.O. also ensures his machine gun unit remains focussed and casualties are evacuated in an orderly way. All this is displayed amidst the detritus of war strewn on the defensive sand dunes of a besieged Dunkirk.

It is a dark, intense and disciplined scene which demonstrates beyond the artwork the high price which was paid, not only on the beaches of Dunkirk, but in ensuring the corridors to Dunkirk remained open, at all costs, to safeguard the liberty we enjoy today.

Defiance under adversity.

Lest We Forget.

John E. Head January 2019.

N.B - Bob Brown started a drawing course several years after the war was over. He never considered himself as an artist rather, a man who dabbled in drawing.

Similar to Capt. Charles Long’s artwork, Bob Brown’s ‘Last Stand at Dunkirk’ reaches out beyond the drawing.

Bob was captured at Le Paradis which formed part of the valiant rear-guard defence that allowed the evacuation of Dunkirk to be successfully accomplished. Whilst not being at Dunkirk, Bob has allowed his experiences in battle, leading up to the surrender at Le Paradis, to be transposed to the Dunkirk beachhead.

With the clever use of shading Bob displays the intensity and the discipline of the B.E.F. which, whilst under constant attack, is stoic in its resistance. It is a scene of total defiance into which you are immediately drawn and placed alongside the mortar team in the foreground. You can feel the concentration that is required under frenzied conditions to ensure the range of the mortar on the identified target is correct. In the background the upright Officer/N.C.O. also ensures his machine gun unit remains focussed and casualties are evacuated in an orderly way. All this is displayed amidst the detritus of war strewn on the defensive sand dunes of a besieged Dunkirk.

It is a dark, intense and disciplined scene which demonstrates beyond the artwork the high price which was paid, not only on the beaches of Dunkirk, but in ensuring the corridors to Dunkirk remained open, at all costs, to safeguard the liberty we enjoy today.

Defiance under adversity.

Lest We Forget.

John E. Head January 2019.

N.B - Bob Brown started a drawing course several years after the war was over. He never considered himself as an artist rather, a man who dabbled in drawing.

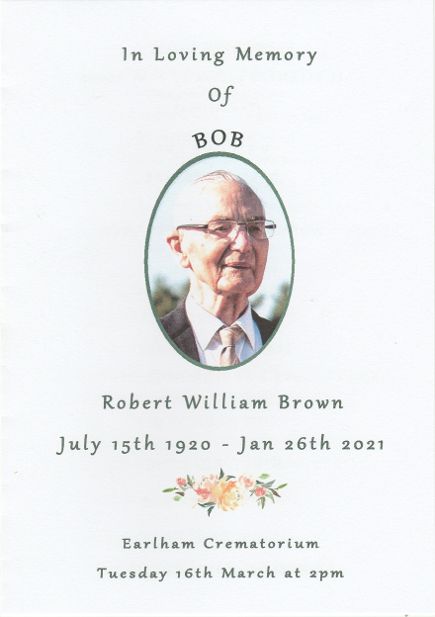

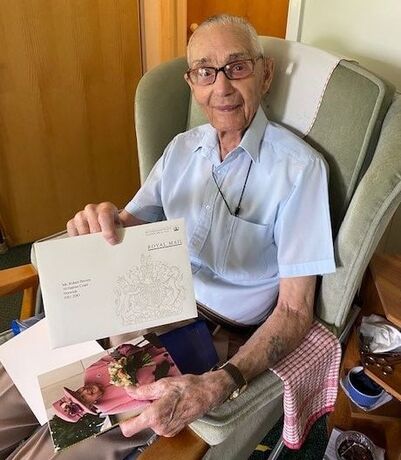

Bob is photographed opposite celebrating his 100th birthday on 15th July, 2020 and showing off his card from Her Majesty the Queen.

Bob died in January 2021. You can also see the front page of the funeral service.

Pictures courtesy of the Brown family and used with their kind permission.

Bob died in January 2021. You can also see the front page of the funeral service.

Pictures courtesy of the Brown family and used with their kind permission.

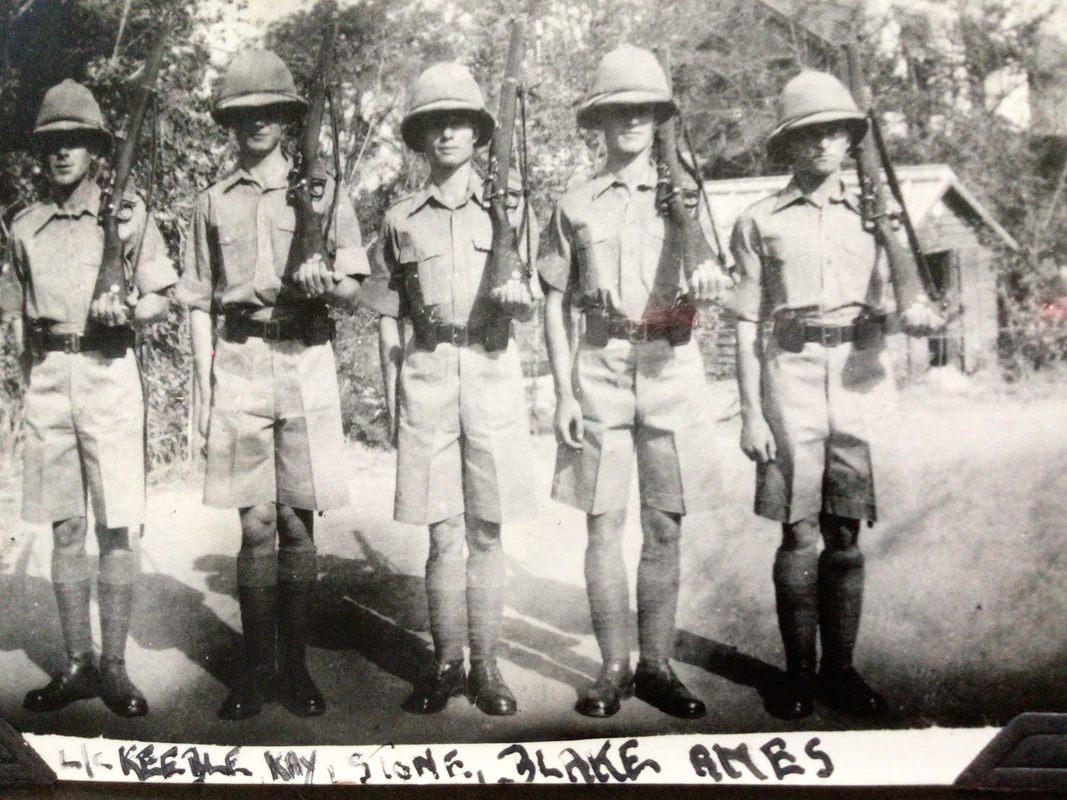

It is likely that the Blake mentioned in this photograph is Bob Brown's mate Alf Blake. Photo courtesy of the Nichols Family.

|

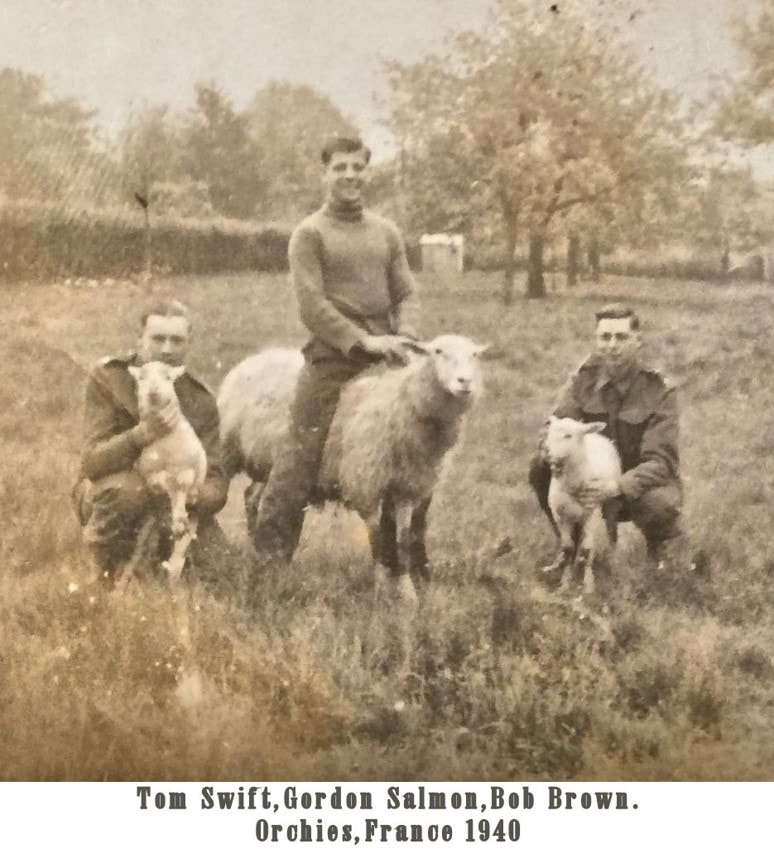

More photographs from the Brown family album.

The top photo shows Bob with Tom Swift and Gordon Salmon at Orchies. The Royal Norfolks were assigned to Orchies (the divisional reserve base) in February 1940 to prepare a new defence line. In March they were moved to Rumempre close to Amiens for 10 days before returning to Orchies where, on 10th May, they were made ready to take up position at Wavre via Valenciennes. We can date the photo between February and May, 1940, with the leaves on the trees. It is likely to have been taken in May. Tom Swift, Gordon Salmon and Bob Brown were all in HQ Company upon embarkation in September 1939. Sadly, Gordon Salmon appears on the Dunkirk Memorial to the Missing and could possibly have been a massacre victim. The photograph on the right shows Bob Brown, Alf Blake and Tom Swift in France 1940. Alf Blake was also in HQ Company upon embarkation in 1939. Alf's name is on the Dunkirk Memorial to the Missing but, backed by Bob's account, it is very unlikely that he was a massacre victim. The photo of Ron Pattison was taken at Bordon in March 1939. This 'Stand-alone' photo must have meant something to Bob and it is likely he was another close friend. Bordon was a military training camp in Hampshire. What then comprised the 3rd Military Brigade was housed there in 1939 but was dispatched to Southampton in September 1939 to become part of the BEF destined for France |