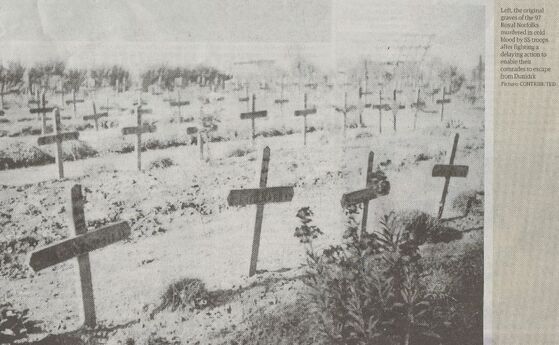

The bodies of those who died in the massacre were originally buried in a mass grave in front of the barn where they fell and then later were buried in a field behind the church (as pictured). This consequently became the Commonwealth War Cemetery as it is today. The original exhumation and removal of the bodies and re-interment took place in 1942 when the then mayor of Lestrem Henri Leleu received an order from the German authorities to remove the bodies to the cemetery within eight days. Work began on May 4th.

Above is a new photograph of the temporary graves at Le Paradis. Photo courtesy of Andrew Whyte and the family of Arthur Preston.

The Massacre at Le Paradis (General Overview)

THE massacre of over 90 British troops at Le Paradis has, quite rightly, gone down in history as a major war crime. The machine-gunning of 97 soldiers, who had surrendered to the German forces, was exactly what it became known as - a massacre and mass murder in cold blood.

Investigations into the event were delayed until 1944 due to the fact that nobody believed the two survivors - Privates William "Bill" O'Callaghan and Albert "Bert" Pooley. At the end of the war, however, even Germans were asking questions about what had gone on in the small village of Le Paradis on 27th May, 1940. Much valuable information was acquired by the Americans and forwarded to the London interrogation centre known as The Cage.

On 24th May, 1940, British and Allied Forces were retreating from the German push forward and trying desperately to reach Dunkirk for evacuation back to the United Kingdom. They were followed by the Germans, who, suddenly, confused everyone by halting their progress which gave additional time for the evacuation. As a result over 338,000 troops made it back to Britain. Not all the troops could evacuate. Some had to stay and fight.

The 3rd Company SS Division Totenkopf consisted of fanatical Nazis, prepared to fight aggressively for the Fatherland. On 24th May, the Totenkopf had been pushing towards the town of Bethune when they came under fire from British troops. Much to their surprise, the German troops were ordered to retreat before pushing forward yet again.

The Second Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment and the Eighth Lancashire Fusiliers were ordered to hold the line at the French villages of Riez du Vinage, Le Cornet Malo and Le Paradis.

On 27th May, the Totenkopf attacked the British at Le Cornet Malo with the death of 150 men from both sides.

Meanwhile the Norfolks had set-up their headquarters at Le Paradis at a farmhouse known as Duriez* Farm. Their orders were confusing but they did their best under the circumstances that prevailed at the time. Eventually the Norfolks, which also included the First Royal Scots, were forced out of the ruined farmhouse and took shelter in a nearby cowshed.

The Norfolks ran out of ammunition late afternoon. There were only 99 men left under the command of Major Lisle Ryder. Ryder ordered his men to surrender after consulting them. They stepped out of the shed with a white flag. German SS Officer Fritz Knoechlein ordered the prisoners to be stripped of their weapons and marched them towards another barn. Lining the 99 British troops against the wall he then ordered two machine gunners to open fire followed by the bayoneting of any survivors. Pistols were also used to finish off any soldiers still alive.

The Germans failed to kill two members of the Norfolks. Bill O'Callaghan was hit in the arm and knocked to the ground. Another body fell on him and Bill decided to play dead. He was aware of the Germans going along the line of dead soldiers and thrusting bayonets into them. They did this to the man who fell on him. Fate then took a hand as a whistle was blown to conclude the matter and the Germans left. Shortly afterwards, Bill was shaken awake, having fallen asleep, by the other survivor, Bert Pooley, who had a shattered leg.

Bill managed to carry and shelter Bert by a woodpile before finding a pig sty to give them more shelter. That was some achievement bearing in mind the injuries to both men and the fact that Bert was well over 6ft tall whilst Bill stood at little more than 5ft 6in.

Bill and Bert survived for three days on raw potatoes and muddy water which they drank from puddles and which made them ill. They were found by Madame Duquenne-Creton and her son Victor who owned the farm and, ignoring the danger to themselves, sheltered the men. The German Wehrmacht 251 Infantry Division came along and took the men as prisoners of war. No action was taken against the Duquenne-Cretons.

Bert was eventually repatriated to England on the grounds that he was no longer a threat to the Germans. Bill O'Callaghan spent the remainder of the war as a prisoner in a number of different camps and was also involved in the infamous 1,000 mile march in 1945. Details of some of his time in these camps formed part of his diary which he brought home after the war and which is featured on this site.

This web site has been set-up to take an in-depth look at all aspects of the massacre and its aftermath with particular reference to Bill O'Callaghan. It uses existing material in the public domain as well as exclusive material from the collection of Bill's son Dennis and other sources which have never before been published. It also features interviews with descendants of those killed at Le Paradis and includes reference to books and a number of newspaper and magazine articles written about the massacre. These are featured at various points on this site.

Sadly the massacre at Le Paradis is still often overlooked and the actions of soldiers in helping to stop the German advance has gone largely unnoticed.

Click here to read a more in depth history of the massacre.

* - Duriez Farm is also spelled with an "s" in a number of publications. We have adopted the spelling with a "z" throughout this web site but both appear to be equally correct.

Investigations into the event were delayed until 1944 due to the fact that nobody believed the two survivors - Privates William "Bill" O'Callaghan and Albert "Bert" Pooley. At the end of the war, however, even Germans were asking questions about what had gone on in the small village of Le Paradis on 27th May, 1940. Much valuable information was acquired by the Americans and forwarded to the London interrogation centre known as The Cage.

On 24th May, 1940, British and Allied Forces were retreating from the German push forward and trying desperately to reach Dunkirk for evacuation back to the United Kingdom. They were followed by the Germans, who, suddenly, confused everyone by halting their progress which gave additional time for the evacuation. As a result over 338,000 troops made it back to Britain. Not all the troops could evacuate. Some had to stay and fight.

The 3rd Company SS Division Totenkopf consisted of fanatical Nazis, prepared to fight aggressively for the Fatherland. On 24th May, the Totenkopf had been pushing towards the town of Bethune when they came under fire from British troops. Much to their surprise, the German troops were ordered to retreat before pushing forward yet again.

The Second Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment and the Eighth Lancashire Fusiliers were ordered to hold the line at the French villages of Riez du Vinage, Le Cornet Malo and Le Paradis.

On 27th May, the Totenkopf attacked the British at Le Cornet Malo with the death of 150 men from both sides.

Meanwhile the Norfolks had set-up their headquarters at Le Paradis at a farmhouse known as Duriez* Farm. Their orders were confusing but they did their best under the circumstances that prevailed at the time. Eventually the Norfolks, which also included the First Royal Scots, were forced out of the ruined farmhouse and took shelter in a nearby cowshed.

The Norfolks ran out of ammunition late afternoon. There were only 99 men left under the command of Major Lisle Ryder. Ryder ordered his men to surrender after consulting them. They stepped out of the shed with a white flag. German SS Officer Fritz Knoechlein ordered the prisoners to be stripped of their weapons and marched them towards another barn. Lining the 99 British troops against the wall he then ordered two machine gunners to open fire followed by the bayoneting of any survivors. Pistols were also used to finish off any soldiers still alive.

The Germans failed to kill two members of the Norfolks. Bill O'Callaghan was hit in the arm and knocked to the ground. Another body fell on him and Bill decided to play dead. He was aware of the Germans going along the line of dead soldiers and thrusting bayonets into them. They did this to the man who fell on him. Fate then took a hand as a whistle was blown to conclude the matter and the Germans left. Shortly afterwards, Bill was shaken awake, having fallen asleep, by the other survivor, Bert Pooley, who had a shattered leg.

Bill managed to carry and shelter Bert by a woodpile before finding a pig sty to give them more shelter. That was some achievement bearing in mind the injuries to both men and the fact that Bert was well over 6ft tall whilst Bill stood at little more than 5ft 6in.

Bill and Bert survived for three days on raw potatoes and muddy water which they drank from puddles and which made them ill. They were found by Madame Duquenne-Creton and her son Victor who owned the farm and, ignoring the danger to themselves, sheltered the men. The German Wehrmacht 251 Infantry Division came along and took the men as prisoners of war. No action was taken against the Duquenne-Cretons.

Bert was eventually repatriated to England on the grounds that he was no longer a threat to the Germans. Bill O'Callaghan spent the remainder of the war as a prisoner in a number of different camps and was also involved in the infamous 1,000 mile march in 1945. Details of some of his time in these camps formed part of his diary which he brought home after the war and which is featured on this site.

This web site has been set-up to take an in-depth look at all aspects of the massacre and its aftermath with particular reference to Bill O'Callaghan. It uses existing material in the public domain as well as exclusive material from the collection of Bill's son Dennis and other sources which have never before been published. It also features interviews with descendants of those killed at Le Paradis and includes reference to books and a number of newspaper and magazine articles written about the massacre. These are featured at various points on this site.

Sadly the massacre at Le Paradis is still often overlooked and the actions of soldiers in helping to stop the German advance has gone largely unnoticed.

Click here to read a more in depth history of the massacre.

* - Duriez Farm is also spelled with an "s" in a number of publications. We have adopted the spelling with a "z" throughout this web site but both appear to be equally correct.