Miscellaneous Documents and Articles

See Also - Le Paradis work in schools

Edward Scallon's Story

It is likely that the following article refers to the massacre. It was written by Anna Galpin in 1995 and comes from Dennis O'Callaghan's collection:

"I was 6 years old in June 1940, about the time of Dunkirk, my grandmother and her youngest daughter (my mother's sister) stayed at our home in Newcastle on Tyne. It had been arranged that in an emergency the family would meet there as it was the closest to the town centre and the railway station. We were waiting for news of my uncle, Edward Scallon, a Chaplain to the forces serving with the BEF.

I was sleeping in a large double bed between my grandmother and my aunt. I awoke in the middle of the night to hear voices; the light was on, the fire burning and there were people in the room. My parents were sitting by the fire and my uncle was sitting on the end of the bed, very oddly dressed. He was wearing a rough khaki shirt and navy blue socks given him by a Dutch sailor. I discovered later that his wet uniform was in a bag in the kitchen.

My uncle was telling how he got home. As everyone was listening to him they did not notice that I was also listening otherwise, I am sure, he would not have told this story.

He and his men had been waiting for three days to be taken off the beaches north of Dunkirk. One night during this time a Sergeant and another soldier from a different regiment came looking for a Roman Catholic Padre who spoke French and/or German. They wanted my uncle to go with them to see someone. My uncle's fellow officers did not want him to go as they did not know the sergeant. But he went.

They walked for about three miles, he thought, along dunes then inland a little. The sergeant and the soldier would tell him nothing. At last they arrived at a farm or cottages where an officer greeted my uncle and thanked him for coming. They took him to the back of the buildings where a man was lying covered with sacks. The officer said the casualty was a German Captain they had found trying to reach the British lines. He left my uncle with the man.

They talked and the Captain said he came from Berlin and was married with a young son. He and his men had captured some British soldiers and were keeping them in a barn. Some SS officers had arrived and had ordered him to tell his men to shoot the British prisoners. The captain had protested and refused. When he continued to refuse the SS Officer ordered some of his SS men to deal with him.

The sacks were turned back.

My uncle said "His chest was cut to ribbons by bayonet thrusts. Only his tunic was holding it together."

The SS had left him for dead so he managed to get away.

My uncle gave him the last rites and they talked a little more. The captain was worried about his wife and son in Berlin in case there were any reprisals taken for his actions. My uncle left him and made his way back to his own unit.

Uncle Eddie wanted to report the incident to someone but when he reached England there was no debriefing. I do not know whether he ever managed to report the episode.

Whether this refers to the men of the Royal Norfolk Regiment or to others I do not know. I was six years old but have never forgotten his story. Like other stories told in the war we never discussed it, particularly as I was not supposed to have heard it. Uncle Eddy died in 1966 and my parents, aunt and grandmother are also now dead.

This was his story of how an enemy also lost his life trying to protect his prisoners."

"I was 6 years old in June 1940, about the time of Dunkirk, my grandmother and her youngest daughter (my mother's sister) stayed at our home in Newcastle on Tyne. It had been arranged that in an emergency the family would meet there as it was the closest to the town centre and the railway station. We were waiting for news of my uncle, Edward Scallon, a Chaplain to the forces serving with the BEF.

I was sleeping in a large double bed between my grandmother and my aunt. I awoke in the middle of the night to hear voices; the light was on, the fire burning and there were people in the room. My parents were sitting by the fire and my uncle was sitting on the end of the bed, very oddly dressed. He was wearing a rough khaki shirt and navy blue socks given him by a Dutch sailor. I discovered later that his wet uniform was in a bag in the kitchen.

My uncle was telling how he got home. As everyone was listening to him they did not notice that I was also listening otherwise, I am sure, he would not have told this story.

He and his men had been waiting for three days to be taken off the beaches north of Dunkirk. One night during this time a Sergeant and another soldier from a different regiment came looking for a Roman Catholic Padre who spoke French and/or German. They wanted my uncle to go with them to see someone. My uncle's fellow officers did not want him to go as they did not know the sergeant. But he went.

They walked for about three miles, he thought, along dunes then inland a little. The sergeant and the soldier would tell him nothing. At last they arrived at a farm or cottages where an officer greeted my uncle and thanked him for coming. They took him to the back of the buildings where a man was lying covered with sacks. The officer said the casualty was a German Captain they had found trying to reach the British lines. He left my uncle with the man.

They talked and the Captain said he came from Berlin and was married with a young son. He and his men had captured some British soldiers and were keeping them in a barn. Some SS officers had arrived and had ordered him to tell his men to shoot the British prisoners. The captain had protested and refused. When he continued to refuse the SS Officer ordered some of his SS men to deal with him.

The sacks were turned back.

My uncle said "His chest was cut to ribbons by bayonet thrusts. Only his tunic was holding it together."

The SS had left him for dead so he managed to get away.

My uncle gave him the last rites and they talked a little more. The captain was worried about his wife and son in Berlin in case there were any reprisals taken for his actions. My uncle left him and made his way back to his own unit.

Uncle Eddie wanted to report the incident to someone but when he reached England there was no debriefing. I do not know whether he ever managed to report the episode.

Whether this refers to the men of the Royal Norfolk Regiment or to others I do not know. I was six years old but have never forgotten his story. Like other stories told in the war we never discussed it, particularly as I was not supposed to have heard it. Uncle Eddy died in 1966 and my parents, aunt and grandmother are also now dead.

This was his story of how an enemy also lost his life trying to protect his prisoners."

Le Paradis Poems By John Head

Why the poems were written -

For some time I felt I needed to place my own thoughts about the Le Paradis atrocity in writing and, in what better way, than through poetry where I could convey my emotions to the reader.

I would try to experience what a surrendered solder was going through being marched to a place where, unknown to him, he was to be executed. Then after death whether these soldiers would ever know how critical their valiant defence of Le Paradis would be to the outcome of the Second World War and whether their sacrifice would be remembered.

In "The Royal Scot," I am him. I have gone through 17 days with little rest in a valiant fighting retreat which often involved hand to hand fighting, constant mortar and Stuka attack with regular breakdowns in communications. To surrender, having done my best, is wretched (verse 2) but somewhat of a relief. In my tiredness, I am oblivious to pain and the removal of my identity tag (verse 3). I think of home and what is going around me is somewhat surreal (verse 4 and 5). The rest I seek becomes eternal (verse 6).

"The Royal Norfolk" is about remembrance as he poses the question will he be remembered after the event for, unlike the corn, he has been scythed down before maturity and before he can harvest his life’s rewards (verse 1). In the verses which follow I respond by telling him that, whilst material things have changed (especially in agriculture), his memory remains steadfast (verses 2, 3 and 4). The final verses (5 and 6) assures him that he is remembered and what he fought for is still preserved in the fields of Norfolk for the generations that followed him.

My emotions behind the experiences of the Royal Scot equally applies to a Royal Norfolk. My emotions behind the remembrance of a Royal Norfolk equally applies to a Royal Scot

For some time I felt I needed to place my own thoughts about the Le Paradis atrocity in writing and, in what better way, than through poetry where I could convey my emotions to the reader.

I would try to experience what a surrendered solder was going through being marched to a place where, unknown to him, he was to be executed. Then after death whether these soldiers would ever know how critical their valiant defence of Le Paradis would be to the outcome of the Second World War and whether their sacrifice would be remembered.

In "The Royal Scot," I am him. I have gone through 17 days with little rest in a valiant fighting retreat which often involved hand to hand fighting, constant mortar and Stuka attack with regular breakdowns in communications. To surrender, having done my best, is wretched (verse 2) but somewhat of a relief. In my tiredness, I am oblivious to pain and the removal of my identity tag (verse 3). I think of home and what is going around me is somewhat surreal (verse 4 and 5). The rest I seek becomes eternal (verse 6).

"The Royal Norfolk" is about remembrance as he poses the question will he be remembered after the event for, unlike the corn, he has been scythed down before maturity and before he can harvest his life’s rewards (verse 1). In the verses which follow I respond by telling him that, whilst material things have changed (especially in agriculture), his memory remains steadfast (verses 2, 3 and 4). The final verses (5 and 6) assures him that he is remembered and what he fought for is still preserved in the fields of Norfolk for the generations that followed him.

My emotions behind the experiences of the Royal Scot equally applies to a Royal Norfolk. My emotions behind the remembrance of a Royal Norfolk equally applies to a Royal Scot

A Royal Scot May 27th, 1940, France

I was there,

That late May afternoon,

A tired surrender following

A valiant defence of a small French hamlet.

Walking out, hands on my head.

It should have been a proud march

With tartan swaying and pipes playing.

Not this. Not this.

I am numb to the feel of the rifle butt

I have no identity. ‘Known unto God’

The smirking faces of my captors

Sickens me. I’m tired.

The Gallic pastures are tainted

By the rapid guns that guard me.

Come Loch Tummel rains

And refresh my face.

Did I not hear the shout ‘Feuer!’

Or see my comrades pirouette before me

Or feel the searing heat enter my flesh?

I hear only the final shot salute.

I return to earth in that bloodied field

As the rains drift softly across Loch Tummel.

At home they celebrate my birthday

Whilst darkness descends on Pitlochry.

© John E. Head 2018

A Royal Norfolk 27th May, 1940, France

Am I forgotten from that day

Surrendered to a sacrifice

In ‘foreign fields’ ere grain was scythed

Before the dawn of Michaelmas?

You are remembered Norfolk man

Above the noise of modern farms

Where once behind your father’s plough

You kept in step and proudly trudged

Throughout those undulating fields

Tarmac arteries now pervade.

In woods which veil the lover’s blush

Your memory is not concealed.

Whilst lichen hides your inscribed name

Upon the village epitaph

It cannot mask your gallant deeds

A nation ever in your debt

Families who once mourned your loss

Now weep with pride, tell of that day

And mark remembrance every year

With plywood cross and poppy red

You are remembered Norfolk man

For in those fields you once prepared

The golden corn salutes the sun

And children’s laughter freely plays

© John E Head 2018

I was there,

That late May afternoon,

A tired surrender following

A valiant defence of a small French hamlet.

Walking out, hands on my head.

It should have been a proud march

With tartan swaying and pipes playing.

Not this. Not this.

I am numb to the feel of the rifle butt

I have no identity. ‘Known unto God’

The smirking faces of my captors

Sickens me. I’m tired.

The Gallic pastures are tainted

By the rapid guns that guard me.

Come Loch Tummel rains

And refresh my face.

Did I not hear the shout ‘Feuer!’

Or see my comrades pirouette before me

Or feel the searing heat enter my flesh?

I hear only the final shot salute.

I return to earth in that bloodied field

As the rains drift softly across Loch Tummel.

At home they celebrate my birthday

Whilst darkness descends on Pitlochry.

© John E. Head 2018

A Royal Norfolk 27th May, 1940, France

Am I forgotten from that day

Surrendered to a sacrifice

In ‘foreign fields’ ere grain was scythed

Before the dawn of Michaelmas?

You are remembered Norfolk man

Above the noise of modern farms

Where once behind your father’s plough

You kept in step and proudly trudged

Throughout those undulating fields

Tarmac arteries now pervade.

In woods which veil the lover’s blush

Your memory is not concealed.

Whilst lichen hides your inscribed name

Upon the village epitaph

It cannot mask your gallant deeds

A nation ever in your debt

Families who once mourned your loss

Now weep with pride, tell of that day

And mark remembrance every year

With plywood cross and poppy red

You are remembered Norfolk man

For in those fields you once prepared

The golden corn salutes the sun

And children’s laughter freely plays

© John E Head 2018

Funeral Notice for Madame Duquenne

Below is the funeral notice for Madame Etienne Duquenne nee Pauline Creton who died on August 19th, 1990 at the age of 86. The funeral service took place in St Joseph Church, Le Paradis on 23rd August, 1990.

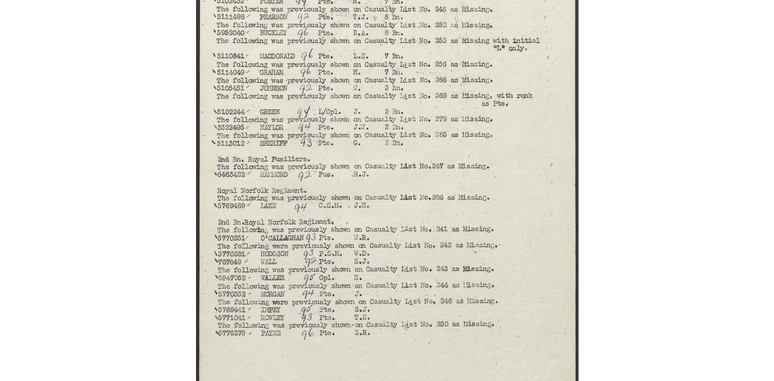

Record of War Casualties and Missing

The following list of war casualties and missing includes the name of Bill O'Callaghan.

Click Here for More Maps and Diagrams

Attempts were made many years ago to obtain a medal to mark the bravery of Private Bill O'Callaghan. Requests were turned down and you can read the letters of refusal by clicking here.

2018 Commemoration Event

Below is an invitation to the 2018 commemoration event from Le Paradis to Dennis O'Callaghan.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

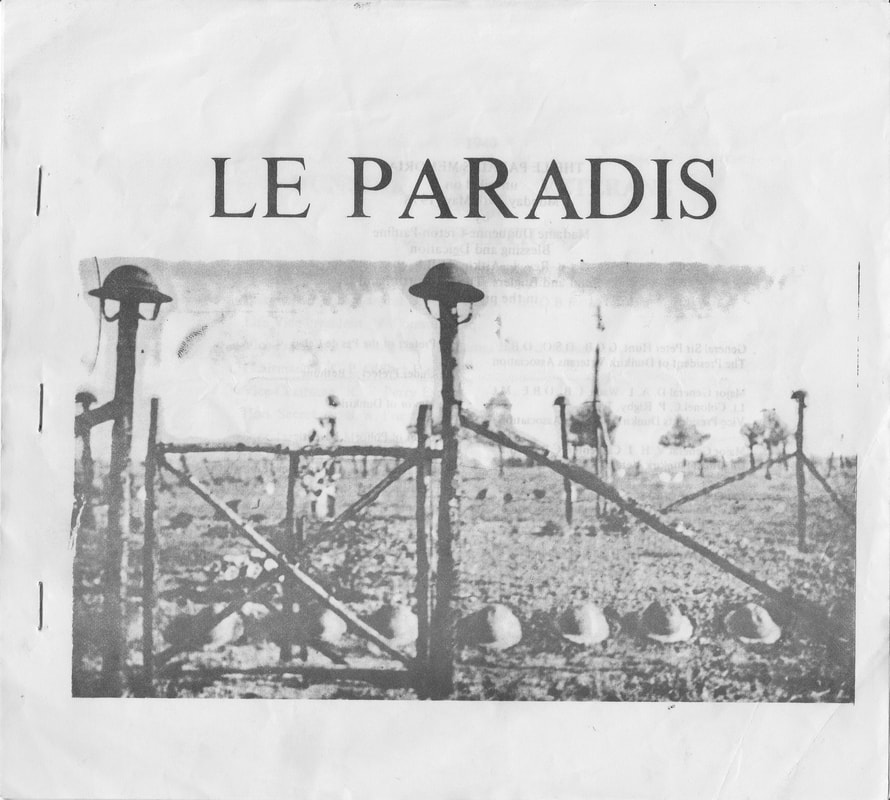

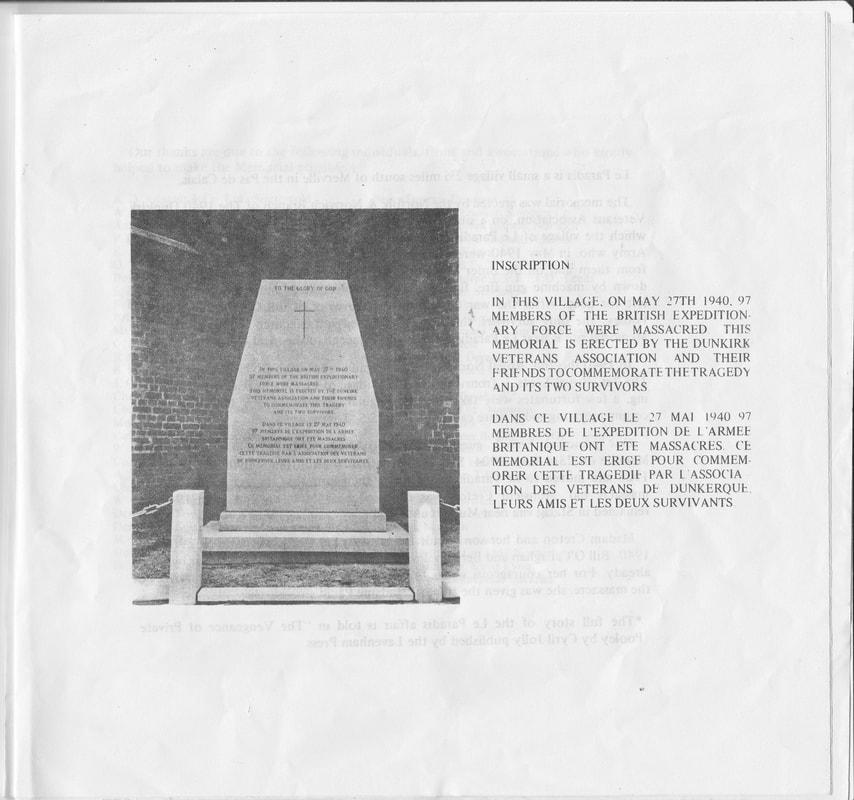

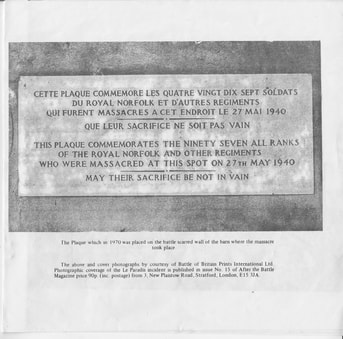

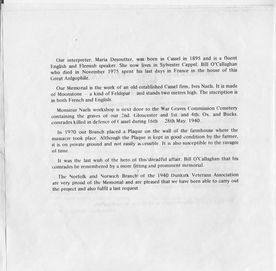

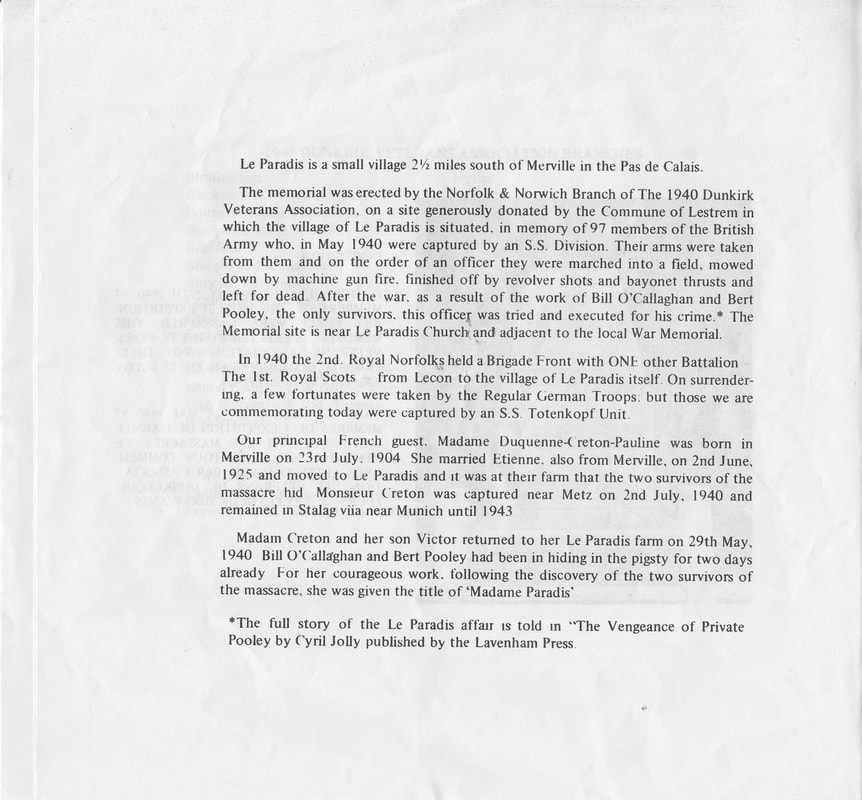

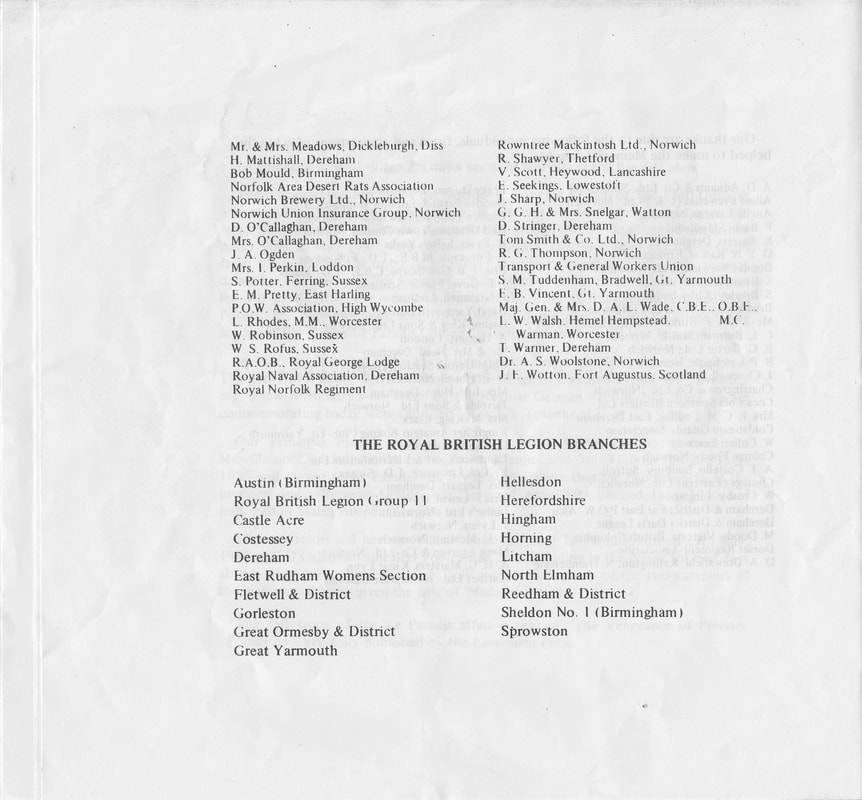

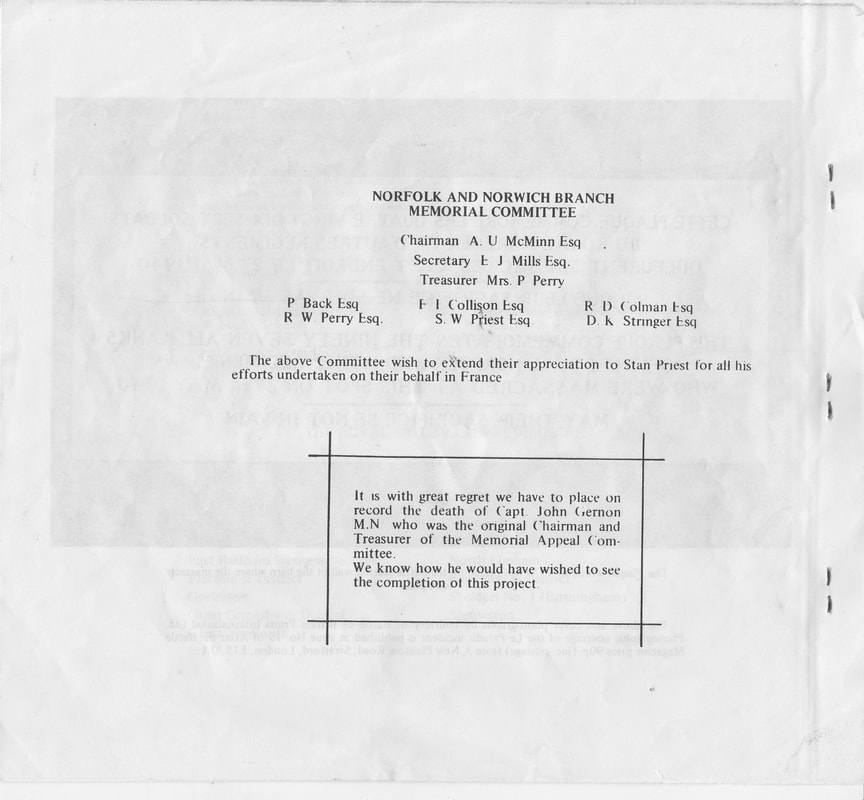

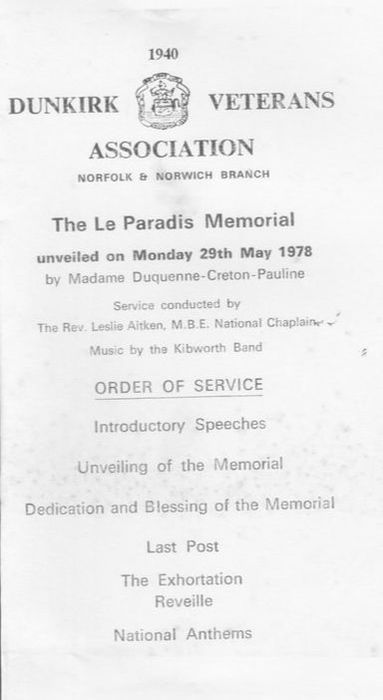

Le Paradis Memorial Brochure - May 1978

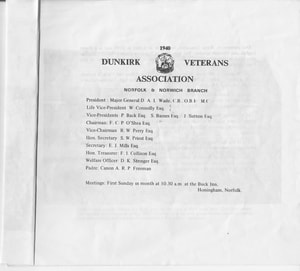

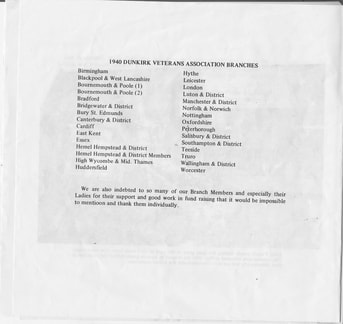

In 1978 a special brochure was produced by the Dunkirk Veterans' Association in respect of the commissioning of the memorial in front of the church owing to the existing memorial being on private land. The brochure is reproduced below.

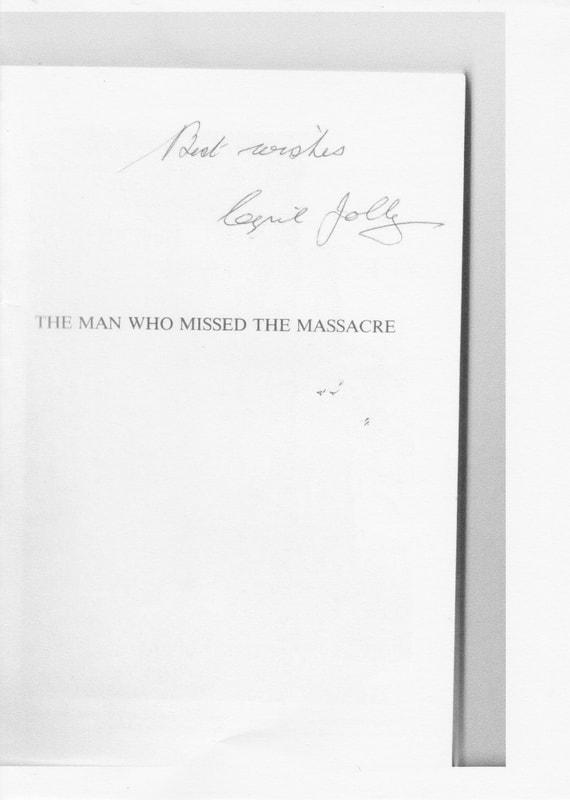

On the left above is a copy of the Dunkirk Veterans' Association programme for the unveiling of a memorial at Le Paradis in 1978. On the right is a signed opening page to Cyril Jolly's book "The Man Who Missed the Massacre."

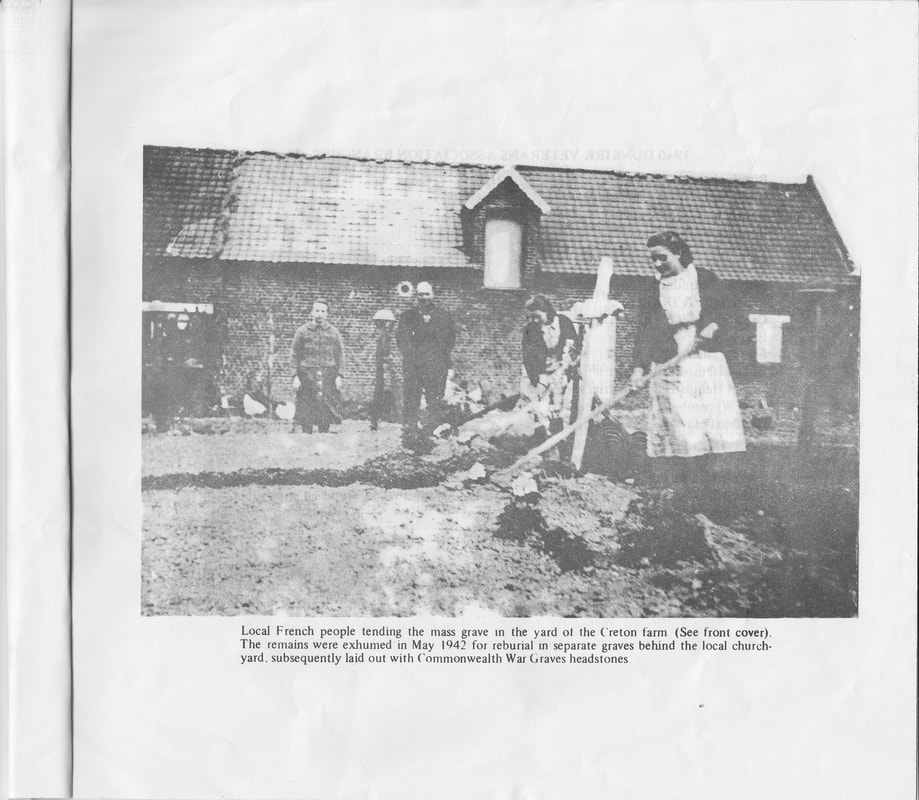

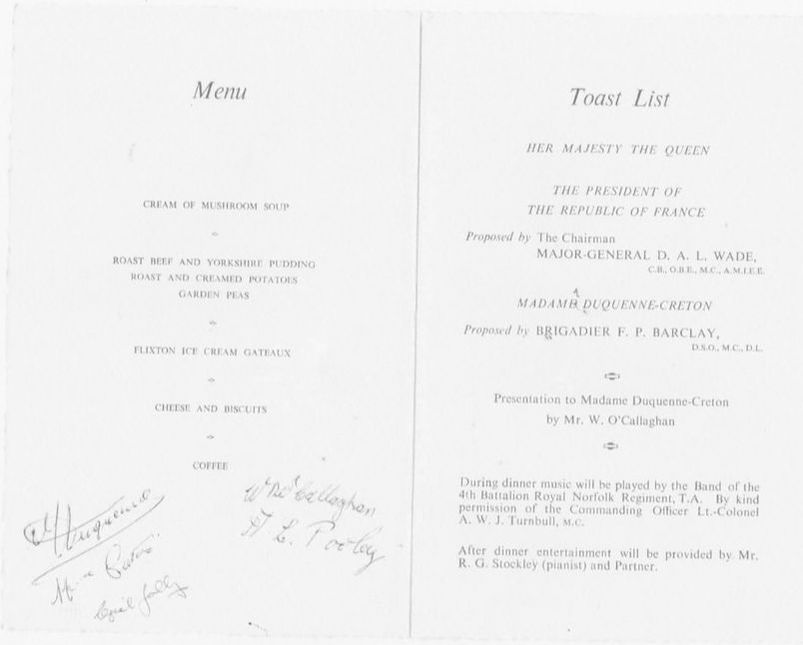

Menu for a commemoration meal for Le Paradis. This one was signed by Madame Pauline Duquenne-Creton, author Cyril Jolly, Bill O'Callaghan and Bert Pooley.