The Surrenders at Duriez Farm in Late Afternoon 27th May, 1940.

The picture above is of the surrender scene shortly before the massacre of the 97 soldiers. This infamous photograph was taken by SS Officer Herbert Brunnegger. Below is a photograph never before published and is believed to have been taken shortly after the surrender at Duriez Farm. It is courtesy of Andrew Whyte and the Preston family.

There is a general misconception that all who surrendered defending Battalion Headquarters Duriez Farm on 27th May 1940 were taken to the barn at Creton’s Farm and massacred. This is incorrect:

To assist: Duriez Farm comprised of two main building; the farmhouse itself and the byre (cow barn). Those who escaped from the farmhouse were taken as prisoners of war and survived. Those in the byre were victims of the massacre when they surrendered.

There were THREE distinct surrenders at Duriez Farm

SURRENDERS ONE and TWO – THE BYRE (COW BARN) SURRENDERS:

It must be appreciated that, other than the enemy, the only two witnesses to the atrocity were Privates Bill O’Callaghan and Bert Pooley.

Whilst statements and recollections in respect of the time of the surrender vary from mid to late afternoon on May 27th 1940 it has generally been accepted that the surrender time was at 17.15 as noted by the Adjutant, Capt. Charles Long. Capt. Long escaped by the farmhouse (see The Ditch Surrender).

The numbers killed in the first surrender attempt vary from three to 12 and from the cross examinations of O’Callaghan and Pooley the German guns also fired on the second surrender and as many as 10 to 12 could have been shot down. Numbers can be clouded by the lack of sleep both O’Callaghan and Pooley had over the 17 days leading up to the surrender and the confused situation which existed around the surrender attempts at the time.

Affidavits and Cross Examinations

To assist the reader the following are transcripts from the O’Callaghan and Pooley affidavits taken from the United Nations War Crimes Commission and their cross examinations undertaken by Mr Field Fisher in front of the Judge Advocate at the Trial of Fritz Knoechlein on Friday 15th October 1948. The affidavits and cross examination transcripts deal purely with the surrender attempts at the byre (cow shed) and the treatment received prior to entering Creton’s Farm where the massacre took place.

The trial of Fritz Knoechlein held in the Curiohaus at Hamburg, opened on October 11th, 1948, before a court of six. Its president was Lt. Col. E. C Van Der Kiste of the Essex regiment. The others were Mr H. Honig (the judge advocate), Major P. Witty, Major C. Champion, Captain J. E. Tracey and Captain A. Preston. Mr T. Field-Fisher was the prosecuting counsel and the counsel for the defence was a Doctor Uhde.

O’Callaghan’s Affidavit (This part of the affidavit begins at the surrender and ends at the gateway to Louis Creton's Farm).

We hung a towel on the end of a rifle, and shortly afterwards all firing ceased. We opened the door, and started to file out with our hands above our heads. The first dozen men out were mown down, then the firing ceased. We marched down to a field about 300 yards away, here we were searched. After we were searched the wounded were attended to, and we were lined-up in threes, and marched across a field. After we had been searched some high ranking German officer (I think he had red lapels on his greatcoat) came up and spoke to the other German officers there (I cannot remember how many there were), and waved his hand, whereupon we moved off. We halted on the road, about 200 yards from where we had been searched, to let some vehicles pass. We started off again to march along the road, and met German troops who behaved in a very brutal manner towards us, hitting us with their rifles and pushing us about. On the march we halted once or twice, and it is possible that one of those halts occurred just before we turned off into a gateway leading into a farm.

O’Callaghan’s Cross Examination (This is taken from the time just before the surrender at Battalion Headquarters, Duriez Farm. O'Callaghan is cross-examined by the prosecution Counsel Mr T. Field-Fisher).

MR FIELD FISHER

Q. Your battalion headquarters were situated in a house?

A. Yes.

Q. Was your battalion, during the course of the fighting that day, cut off and surrounded

A. Yes.

Q. Do you remember the last communication you had with your brigade headquarters that day?

A. It was about 12 o’clock.

Q. Twelve o’clock midday?

A. Yes, midday.

Q. And what was that communication?

A. That came from brigade, that it was more or less every man for himself.

Q. Were you then working on the set yourself?

A. No.

Q. Was the set subsequently destroyed?

A. It was.

Q. That would be about 12 o’clock. What was the next thing that happened after that?

A. Our company commander told us – we were all, about half a dozen men down the cellar, I was one of them – to make our way to the barn one at a time.

Q. You mention a barn, was that the barn near the building where battalion headquarters was, or was it where battalion headquarters itself was?

A. That was just on the left of the farm. It was more or less a continuation of the farm.

Q. And was it then or subsequently that it was decided to surrender?

A. It was decided afterwards to surrender.

Q. About what time was that decision made?

A. I should say between 2.30 and 3 o’clock.

Q. Did you have any wounded at battalion headquarters?

A. Yes.

Q. Where were they?

A. Some were in the barn and some were lying outside.

Q. Who was your senior officer, at the time in charge of battalion headquarters?

A. Major Ryder.

Q. What had happened to the battalion adjutant, do you know?

A. I saw the battalion adjutant lying at the top of the cellar steps, wounded, when I came out of the barn.

Q. How was the surrender carried out? Will you describe what you did?

A. First of all, a towel was hung out of the window of the barn on a rod and about three men went out. They were immediately shot down.

Q. About how far away were the enemy at the time of the surrender? Could you see them?

A. I could not see them myself from where I was.

Q. Now from which direction was the enemy attack coming – the troops to whom the surrender was made? Was it coming from the north, south, east or west? Will you show on the map? (Witness indicates on the map)

COURT ORDERLY: He points towards the top right corner of the map, Sir.

MR FIELD FISHER

Q. The attack was coming from a south-westerly to a north-easterly direction? After these men had been shot down, what happened then? Did you try again?

A. Yes, after a while, five or ten minutes we decided to walk out with our hands above our heads.

Q. And did you do that?

A. We did that.

Q. Was that successful? Was the surrender accepted?

A. The first few men were shot down, I should say ten or a dozen of them

Q. Before you surrendered, what had you done with your weapons and any remaining ammunition that you had?

A. We destroyed them, broke them up and threw them in the pond outside the farmhouse.

Q. Have you any idea how many British surrendered at the same time as you, at this particular place?

A. I should say when I was in the barn there were roughly 45-50.

Q. When you had your surrender accepted, what happened then?

A. We were all marched down into a field behind this barn; we were searched and some of our identity discs were removed.

Q. Now just one moment. In which direction were you taken off to be searched, the direction of the enemy or back from where you had come?

A. In the direction of the enemy.

Q. So you were taken somewhere in a south or south-westerly direction from the surrender?

A. Yes

Q. Did you walk along the roads or in the fields?

A. We were in a field, we left the barn.

Q. How far do you think you went before you were searched, approximately?

A. About 300 yards, I think.

Q. You say that in some cases your identity tags were torn off you while you were being searched. Did anything also untoward happen while you were being searched? How were you treated?

A. I personally was treated not too badly at that point but I saw others being searched and they were being treated very brutally.

Q. What sort of things were happening to them?

A. They were struck with hands and rifle butts by the Jerries.

Q. Did you have any wounded people with you, I mean walking wounded, at this time?

A. Yes, quite a few.

Q. Did you see any German officers at the time you were being searched or at the time of surrender?

A. I think I saw one or two in the field while we were actually being searched.

Q. Did you see any of the German soldiers reprimanded by their officers or N.C.Os on this occasion, when the search was going on?

A. No.

Q. After the search was over, what happened then?

A. The wounded had been dressed.

Q. Who did that?

A. Our stretcher bearers. Then we were formed up in threes and marched across the field and on to a road.

Q. About how many of you do you think there were by this time?

A. I estimated between 75 and 80.

Q. Were they all British Soldiers, or was there anyone else with you?

A. I think there was one Frenchman with us.

Q. Do you know how he came to be there? Had he been with you during the fighting?

A. I think he joined our battalion the day before we actually surrendered.

Q. You say you reached a road after you were all marched off from being searched. Could you identify that road on the map, say in which direction it was running or anything which may indicate which road you mean?

A. I think that was it (indicating the position on the map) but I am not sure.

Q. Has it got a name on the map, or anything by which you can identify it? Well, if you are not sure let us just go back a moment over your evidence. You indicated where you thought the surrender took place at battalion headquarters, so let us start from that point. Then you say when you surrendered you went in the direction of the enemy, and you continued in that direction behind the enemy lines, so to speak, to where you were searched, a matter of a few hundred yards, and you were searched in a field. Then you say you were marched off again from there, then you struck a road. Does that help you to place it on the map? Was the road running in an east/west direction or north to south, can you remember that? (Witness indicates on the map).

COURT ORDERLY: He is pointing down the road to the bottom left hand corner, Sir.

MR. FIELD FISHER. In which general direction is the road running?

COURT ORDERLY: East/west, Sir.

MR. FIELD FISHER: Well, having got as far as that, do you think you can see it on the map? If you cannot be sure, let us not press you about it.

A. No, I cannot be sure where it is on the map.

Q. Very well. At any rate it was a road that you reached which was running in a general easterly/westerly direction?

A. Yes.

Q. Was it a road you had been along yourself the previous day, or during the course of the battle, can you remember?

A. No, I cannot remember.

Q. What sort of road was it, quite a small one or a main road or what?

A. I should say it was a second class road.

Q. A second class minor road, it had hedges ditches or anything?

A. I think there was a ditch on the left hand side.

Q. When you got on to this road, did you continue marching along it or did you halt and cross it, or what did you do?

A. When we came off the field and on to the road we turned left.

Q. Yes? Did you see any transport of any sort on the road?

A. Yes there was quite a lot of German lorries and German soldiers marching.

Q. And where was the transport, on the other side of the road from you or did you have to go to the other side of the road to pass it?

A. That was on the right hand side of the road.

Q. So you were marching along the left hand side of the road?

A. Yes

Q. And if you then turned left on to this road, I take it you were marching in a west/east direction?

A. Yes I think we were.

Q. What was the next thing that happened when you found yourselves on the road?

A. We were walking and then we halted.

Q. Did you walk far before you halted?

A. Not a very great distance, I think, not more than a hundred yards.

Q. About a hundred yards and then you halted. Still on the left hand side of the road?

A. Still on the left hand side of the road, yes.

Q. Were you then in an orderly marching column, or were you straggling out?

A. We were in an orderly column, so far as I could judge.

Q. About how far from the front of the column were you, half way along, or a quarter, or where?

A. I judged I was about half way.

Q. Where did you have your hands at this time?

A. Behind our heads.

Q. All of you?

A. All those who were able, unless they were wounded in the arms.

Q. Did you see any other ill treatments while you were marching that short distance along the road or while you halted?

A. Yes I personally got struck in the ribs, and I also saw some of my other comrades hit with fists and rifle butts.

Q. There is one question I should like to ask you – when you were searched or at any time, were you questioned, interrogated in any way, or did you see anybody else interrogated?

A. I was asked by the German who searched me what regiment I belonged to, and I would not answer him.

Q. Was that all you were asked?

A. That was all I was asked.

Q. There was no official interrogation of you or any of the other prisoners?

A. Not as far as I could see.

Q. Did you at that time have any inkling of what was going to happen?

A. No I did not.

Q. Had any indication been given to you by any of the Germans as to what was going to happen?

A. No, not to me anyway.

Q. Did you hear them say anything to anyone else?

A. No; I could not understand German, but our battalion commander asked the Germans if we were going to be shot and they said “No”; then we asked our battalion commander if we were going to be shot and he said: “No, they dare not do that”

Q. How would you describe the temper of the German soldiers at this time, generally speaking?

A. Very devilish, very bad.

Q. Now we have reached the stage where you have halted on the road. What was the next thing that happened then?

A. We went along a little further and I think we had another little halt.

Q. And then?

A. Then I think we had two or three halts from coming on the road before coming to this farmhouse.

Q. You reached some sort of farmhouse; as you were marching along the road, was that on the right hand side of the road or on the left?

A. That was on our right hand side as we just turned round; I think there was a small gateway.

Q. I want you to visualise that you are marching down the road towards me; you have not started to turn anywhere; was the farm lying on that side of the road (indicating) or on that side? On the right or on the left?

A. My right.

Q. On your right hand side. Did you notice a field or anything like that on the right hand side of the road, before you came to the house, the farm?

A. No, I did not.

Q. Now you mentioned a gateway. Was this on the same side of the road as the farm or the other side?

A. That was on the same side as the farm.

Q. You mentioned turning – did you halt again anywhere near this farm before you turned anywhere, or did you just march straight to wherever you went?

A. I think we halted just before we got to the gate.

At this point in the cross examination, the surrender and aftermath (treatment) is complete and the questionning continues as O'Callaghan turns with the column through the gateway to the scene of the massacre. See massacre presently under construction.

Pooleys Affidavit (This part of the affidavit begins at the surrender and ends at the gateway of Louis Creton's Farm).

The first attempt to surrender was made by three men who walked into the open displaying a white cloth. They immediately came under heavy machine gun fire. The second attempt was then made by all of us running out into the open with our hands in the air. No further fire came from the enemy who stood up and cheered and a German officer ordered us to come forward with our hands in the air. No further fire came from the enemy who stood up and cheered and a German Officer ordered us to come forward with our hands in the air. We were lined up and searched, our helmets were struck from our heads and our equipment and gas marks were forcibly removed.

We had no weapons with us as these had been destroyed before we surrendered. Not one of us to my knowledge still possessed a weapon when we were searched by the Germans. We were told be an English speaking NCO that any wounded could sit down, whereupon some of us did. I was one of those (I had been hit in the left arm and right hip, but not seriously wounded). But no sooner had I sat down then I received a brutal kick in the ribs from a German soldier and was ordered to stand up. During the march which then took place several of us were struck because we did not answer questions or were not quick enough in obeying the orders of the Germans which naturally were unintelligible to us. During tis our wounded were being brought out of the farm house by our own stretcher bearers, but I do not know where they were taken.

After some 15 minutes we were ordered to form up on the road with our hands clasped behind the backs of our heads. During the process some of us were struck with rifle butts while standing in the ranks. The guards who did this were not reprimanded by their officers or NCOs. While we were standing there our numbers must have swollen by the addition of other prisoners because when I turned round I could see that the column had lengthened. I do not know where these additional men came from. At this time I estimate the number of prisoners in the column to have been 65 at the very least. We were then ordered to march along the road, all the time being struck and cuffed by the guards and any other Germans passing us. Our direction at this time appeared to be westerly across a road leading to LE PARADIS until we came in the vicinity of another farm house with a field adjoining it on the western side.

We halted on the road for 2 or 3 minutes. During this time a German took from my pocket a packet of cigarettes and when I turned to look at him he struck me with his rifle knocking me through the ranks. An unbroken line of German transport was standing on the right hand side of the road facing us.

We were then ordered to march again and it was at this moment I saw what had been prepared for us.

Pooley’s Cross Examination (This is taken from the time just before the surrender at battalion Headquarters Duriez Farm. Pooley is cross examined by the prosecution counsel Mr T. Field-Fisher).

Q. What was the approximate strength, do you suppose, of the remnants of the Norfolks which were holding out there?

A. I should say about 45.

Q. That is in the neighbourhood of the house in question.

A. Yes

Q. And who was commanding these remnants?

A. Major Ryder was the Colonel, Sir.

Q. What was the ammunition position by about the end of the morning of the 27th May?

A. We only had small arms ammunition left, we had no mortar ammunition and we had very little small arms stuff at all.

Q. What did Major Ryder decide to do?

A. Major Ryder suggested that we had performed everything which we had been asked to do and he could therefore see no further object in resisting any longer and thus wasting more lives.

Q. So was in fact an attempt to surrender made?

A. Yes.

Q. How was that done?

A. Three men went out from the house, through an outhouse door, holding a piece of white material. They immediately came under heavy m/g fire.

Q. Were they shot down?

A. They were shot down.

Q. Were they armed when they went out with this piece of white material?

A. No, they had left their arms in the outhouse.

Q. And was another attempt to surrender then made?

A. Yes.

Q. How was that done?

A. By everybody who was in a position to walk, walking out from the building with their hands raised.

Q. And did the people who came out thus, come under any fire or not, at that time?

A. At first, when we came out, before our intention was clear to the enemy, but I believe when our intention was clear to them the fire ceased.

Q. You said “all those who were able to walk”- did you leave many wounded at that time?

A. From my own knowledge, we had a good few wounded in the cellar; the exact number, I do not know.

Q. They were in the cellar of battalion headquarters?

A. Yes.

Q. And what about the people who came out to surrender, were they all, completely fit and whole men, or were some of them walking wounded?

A. Some of them were wounded, I was one of them.

Q. How was the surrender accepted by the Germans?

A. When the fire ceased, the enemy stood up from their positions and shouted and cheered.

Q. About how far from your last position at battalion headquarters do you suppose the advance German troops were?

A. Between 300 and 400 yards

Q. And from what direction were they attacking? Would you show on the map? Where they coming from the southerly, westerly, northerly or which direction?

MR. INTERPRETER: Do you want the witness to indicate with an arrow, Sir?

MR. FIELD FISHER: Yes the general direction of the German attack, the troops to whom they surrendered.

(The witness marks the position on the Map. Exhibit No. 1, and it is shown to the court). (The direction indicated is west to east).

MR FIELD FISHER:

Q. When the surrender was accepted by the Germans, what was the next thing that took place?

A. We were assembled in a field; our equipment was taken from us, including our gas masks, our helmets were struck from our heads; we were searched, all our clothing, but nothing was taken from us. It seemed to be a very perfunctory search, in my case.

Q. It did not really look as if they were searching for anything?

A. No, it did not seem that they were searching for anything in particular.

Q. Where did this search take place? Did you have to march to the place you were searched, or did it take place on the spot where the surrender was accepted?

A. It took place about 400 yards away, that would be the approximately the position of the enemy troops.

Q. About where their advance positions were?

A. Yes.

Q. And how did you get to that place, did you march along the roads or in the fields?

A. We walked along a field.

Q. Would that be on the north or south side of the road which is marked on the plan as Rue du Paradis?

A. It would be on the north side of the road.

Q. When all of you came out of battalion headquarters to surrender, did you have any arms in your hands at all?

A. No.

Q. What about the ammunition, had you got rid of what little you had?

A. All the remaining ammunition was thrown in the pond.

MR FIELD FISHER;

Q. Now we were just dealing with the time when you were searched, and certain ill-treatments which you described took place. Now after the march was concluded, what was the next thing that happened?

A. After standing around a while in the field – about half- an- hour I should say – we were ordered to form up on the road.

Q. That would be the road to the south, the Rue du Paradis, which is marked on the plan?

A. Yes.

Q. What sort of formation were you formed up in? Were you in threes?

A. We were formed up in threes with our hands clasped on our heads.

Q. Did anything happen to you while you were being formed up? Did any other ill treatments take place, or anything like that?

A. The guards were walking up and down the column. Anybody who was speaking or moving or looking round would be struck. I myself was struck be a German soldier with his rifle. He took 20 cigarettes out of my pocket. I turned and looked at him; he struck me with his rifle and knocked me through the ranks.

Q. What did he strike you with?

A. His rifle butt.

Q. On what part of your body?

A. The left side of my face.

Q. Did he do damage to you?

A. He knocked two of my teeth out and loosened others.

Q. Did you see that guard or any of the other guards reprimanded by any senior officer or N.C.O.?

A.The German soldiers seemed to be out of control. Nobody reprimanded them.

Q. When you formed up on the road, were there still about 40 to 60 of you, or more of you?

A. There were more when we were formed up on the road than I had previously seen in the Battalion H.Q.

Q. Did you see any German transport on the road?

A. Yes. There was a stationary column of German transport on the right hand side of the road facing us.

Q. And were you then ordered to march?

A. Yes we received then order to march.

Q. Did you see who gave the order to march, or did you hear where it came from?

A. I don’t know who issued the order. I simply received it from a German soldier standing by.

Q. While you were marching, did any ill-treatment take place?

A. We were prodded, but I did not notice anything outstanding at that time.

Q. And then did you come to a gate leading into a farmyard?

A. Yes. We halted on the road about 15 yards from the entrance to a field.

Q. I would like you to look at the map please, and indicate you can where this farmyard with the gate was.

(Witness indicates the point on the map with a pencil mark)

Q. You have marked a spot very near where there is a small black dot with a little cross above it, which is a shrine, I think you will see from the legend of the map. Do you remember that shrine at the time?

A. Yes. I saw that. It is the usual thing which you see in France dotted along the roads.

Q. Now, the entrance to this farm, the gate, was that gate directly off the Rue du Paradis.

A. Yes

Q. It gave on to the road?

A. It gave on to the road, yes.

Q. I want you to look at the rest of these photographs. (Photographs shown to the witness) Now, do you recognise the place represented by the other photographs – not the top one you have already identified, but the others on that page and on the other page?

A. Yes.

Q. Is that the place where what you are going to describe took place?

A. That is the place.

THE JUDGE ADVOCATE: Which photograph is that?

Mr Field FISHER: That is all the photographs, sir, except under 1. They are all of the same place taken from different viewpoints, and I think on the first page of the photographs there is a gateway shown into a field looking on a little road. (To witness) Is that the gateway in question?

A. That is the gateway in question

Q. One point I would just like to make. Have you visited tis village since the war?

A. Yes. I went over there in September 1946.

Q. And from your memory and from your reconstruction of it when you were over since the war, are you now quite sure of the identity of the place?

A. Absolutely.

At this point in the cross examination, the surrender and aftermath (treatment), is complete and the questioning continues as Pooley turns with the column through the gateway to the scene of the massacre. See under massacre (under construction).

The Surrender at the cow barn described in Cyril Jolly’s book The Vengeance of Private Pooley

This is extremely important as Cyril Jolly was fortunate to interview the two witnesses to the massacre. The following extract is produced by kind permission of the Jolly family.

The C.O. waited for a moment then said….”No….there’s little we can do”

There followed a long, tense pause, then the C.O. said, “Men, I call on you to surrender. Sergeant-Major get a towel and tie it to a rifle.”

Someone rummaged in a corner among some kit and brought out a towel, not freshly laundered, not unsoiled, but a white towel, the symbol of defeat. A Platoon Sergeant- Major fasted it to a rifle then moved to the backdoor of the cowshed, opposite the one they had entered. It opened onto a meadow, and one hundred and fifty yards away the Germans were firing from ditches and banks. The Sergeant thrust the rifle and towel through the slightly opened upper half of the door and held it thus for two or three minutes. The firing stopped.

“Open the Door” commanded the C.O.

“Follow me” said the Platoon Sergeant-Major holding the rifle aloft with the faintly fluttering flag. Then he went out, five or six men at his heels. He had not gone ten paces before a machine-gun opened fire on them and the Platoon Sergeant-Major and three or four men fell shouting and groaning. The rest of the men in the open rushed back and tried to get into the cow-house but many of those pressing behind, inside, not realising what had happened, did not give ground. For a moment it seemed that the men in the front would panic, but an officer rapped out an order and the door was closed. Again the firing ceased. Five more minute’s passed; then it was decided to make another attempt. An officer shouted “We’re coming out now.” Then again the towel was put out and with hands above their heads the men filed out – five, six, seven, eight. Pooley was among the first. Suddenly from behind a long bank and in ditches the Germans stood up, whooping triumphantly, waving their rifles excitedly.

Editor's Note

Looking through our records we believe that the Platoon Sergeant- Major who led the first surrender attempt may have been PSM Jack Whitlam who was positively identified upon exhumation after the massacre. In Bob Brown’s memoirs the following was noted.

This was now the middle of the afternoon. CSM Whitlam came round with the rum jar and said: "We might as well have this before the Jerries get it. " I had nearly half a mug and couldn't see for a while as the water streamed out of my eyes."

To assist: Duriez Farm comprised of two main building; the farmhouse itself and the byre (cow barn). Those who escaped from the farmhouse were taken as prisoners of war and survived. Those in the byre were victims of the massacre when they surrendered.

There were THREE distinct surrenders at Duriez Farm

SURRENDERS ONE and TWO – THE BYRE (COW BARN) SURRENDERS:

It must be appreciated that, other than the enemy, the only two witnesses to the atrocity were Privates Bill O’Callaghan and Bert Pooley.

Whilst statements and recollections in respect of the time of the surrender vary from mid to late afternoon on May 27th 1940 it has generally been accepted that the surrender time was at 17.15 as noted by the Adjutant, Capt. Charles Long. Capt. Long escaped by the farmhouse (see The Ditch Surrender).

The numbers killed in the first surrender attempt vary from three to 12 and from the cross examinations of O’Callaghan and Pooley the German guns also fired on the second surrender and as many as 10 to 12 could have been shot down. Numbers can be clouded by the lack of sleep both O’Callaghan and Pooley had over the 17 days leading up to the surrender and the confused situation which existed around the surrender attempts at the time.

Affidavits and Cross Examinations

To assist the reader the following are transcripts from the O’Callaghan and Pooley affidavits taken from the United Nations War Crimes Commission and their cross examinations undertaken by Mr Field Fisher in front of the Judge Advocate at the Trial of Fritz Knoechlein on Friday 15th October 1948. The affidavits and cross examination transcripts deal purely with the surrender attempts at the byre (cow shed) and the treatment received prior to entering Creton’s Farm where the massacre took place.

The trial of Fritz Knoechlein held in the Curiohaus at Hamburg, opened on October 11th, 1948, before a court of six. Its president was Lt. Col. E. C Van Der Kiste of the Essex regiment. The others were Mr H. Honig (the judge advocate), Major P. Witty, Major C. Champion, Captain J. E. Tracey and Captain A. Preston. Mr T. Field-Fisher was the prosecuting counsel and the counsel for the defence was a Doctor Uhde.

O’Callaghan’s Affidavit (This part of the affidavit begins at the surrender and ends at the gateway to Louis Creton's Farm).

We hung a towel on the end of a rifle, and shortly afterwards all firing ceased. We opened the door, and started to file out with our hands above our heads. The first dozen men out were mown down, then the firing ceased. We marched down to a field about 300 yards away, here we were searched. After we were searched the wounded were attended to, and we were lined-up in threes, and marched across a field. After we had been searched some high ranking German officer (I think he had red lapels on his greatcoat) came up and spoke to the other German officers there (I cannot remember how many there were), and waved his hand, whereupon we moved off. We halted on the road, about 200 yards from where we had been searched, to let some vehicles pass. We started off again to march along the road, and met German troops who behaved in a very brutal manner towards us, hitting us with their rifles and pushing us about. On the march we halted once or twice, and it is possible that one of those halts occurred just before we turned off into a gateway leading into a farm.

O’Callaghan’s Cross Examination (This is taken from the time just before the surrender at Battalion Headquarters, Duriez Farm. O'Callaghan is cross-examined by the prosecution Counsel Mr T. Field-Fisher).

MR FIELD FISHER

Q. Your battalion headquarters were situated in a house?

A. Yes.

Q. Was your battalion, during the course of the fighting that day, cut off and surrounded

A. Yes.

Q. Do you remember the last communication you had with your brigade headquarters that day?

A. It was about 12 o’clock.

Q. Twelve o’clock midday?

A. Yes, midday.

Q. And what was that communication?

A. That came from brigade, that it was more or less every man for himself.

Q. Were you then working on the set yourself?

A. No.

Q. Was the set subsequently destroyed?

A. It was.

Q. That would be about 12 o’clock. What was the next thing that happened after that?

A. Our company commander told us – we were all, about half a dozen men down the cellar, I was one of them – to make our way to the barn one at a time.

Q. You mention a barn, was that the barn near the building where battalion headquarters was, or was it where battalion headquarters itself was?

A. That was just on the left of the farm. It was more or less a continuation of the farm.

Q. And was it then or subsequently that it was decided to surrender?

A. It was decided afterwards to surrender.

Q. About what time was that decision made?

A. I should say between 2.30 and 3 o’clock.

Q. Did you have any wounded at battalion headquarters?

A. Yes.

Q. Where were they?

A. Some were in the barn and some were lying outside.

Q. Who was your senior officer, at the time in charge of battalion headquarters?

A. Major Ryder.

Q. What had happened to the battalion adjutant, do you know?

A. I saw the battalion adjutant lying at the top of the cellar steps, wounded, when I came out of the barn.

Q. How was the surrender carried out? Will you describe what you did?

A. First of all, a towel was hung out of the window of the barn on a rod and about three men went out. They were immediately shot down.

Q. About how far away were the enemy at the time of the surrender? Could you see them?

A. I could not see them myself from where I was.

Q. Now from which direction was the enemy attack coming – the troops to whom the surrender was made? Was it coming from the north, south, east or west? Will you show on the map? (Witness indicates on the map)

COURT ORDERLY: He points towards the top right corner of the map, Sir.

MR FIELD FISHER

Q. The attack was coming from a south-westerly to a north-easterly direction? After these men had been shot down, what happened then? Did you try again?

A. Yes, after a while, five or ten minutes we decided to walk out with our hands above our heads.

Q. And did you do that?

A. We did that.

Q. Was that successful? Was the surrender accepted?

A. The first few men were shot down, I should say ten or a dozen of them

Q. Before you surrendered, what had you done with your weapons and any remaining ammunition that you had?

A. We destroyed them, broke them up and threw them in the pond outside the farmhouse.

Q. Have you any idea how many British surrendered at the same time as you, at this particular place?

A. I should say when I was in the barn there were roughly 45-50.

Q. When you had your surrender accepted, what happened then?

A. We were all marched down into a field behind this barn; we were searched and some of our identity discs were removed.

Q. Now just one moment. In which direction were you taken off to be searched, the direction of the enemy or back from where you had come?

A. In the direction of the enemy.

Q. So you were taken somewhere in a south or south-westerly direction from the surrender?

A. Yes

Q. Did you walk along the roads or in the fields?

A. We were in a field, we left the barn.

Q. How far do you think you went before you were searched, approximately?

A. About 300 yards, I think.

Q. You say that in some cases your identity tags were torn off you while you were being searched. Did anything also untoward happen while you were being searched? How were you treated?

A. I personally was treated not too badly at that point but I saw others being searched and they were being treated very brutally.

Q. What sort of things were happening to them?

A. They were struck with hands and rifle butts by the Jerries.

Q. Did you have any wounded people with you, I mean walking wounded, at this time?

A. Yes, quite a few.

Q. Did you see any German officers at the time you were being searched or at the time of surrender?

A. I think I saw one or two in the field while we were actually being searched.

Q. Did you see any of the German soldiers reprimanded by their officers or N.C.Os on this occasion, when the search was going on?

A. No.

Q. After the search was over, what happened then?

A. The wounded had been dressed.

Q. Who did that?

A. Our stretcher bearers. Then we were formed up in threes and marched across the field and on to a road.

Q. About how many of you do you think there were by this time?

A. I estimated between 75 and 80.

Q. Were they all British Soldiers, or was there anyone else with you?

A. I think there was one Frenchman with us.

Q. Do you know how he came to be there? Had he been with you during the fighting?

A. I think he joined our battalion the day before we actually surrendered.

Q. You say you reached a road after you were all marched off from being searched. Could you identify that road on the map, say in which direction it was running or anything which may indicate which road you mean?

A. I think that was it (indicating the position on the map) but I am not sure.

Q. Has it got a name on the map, or anything by which you can identify it? Well, if you are not sure let us just go back a moment over your evidence. You indicated where you thought the surrender took place at battalion headquarters, so let us start from that point. Then you say when you surrendered you went in the direction of the enemy, and you continued in that direction behind the enemy lines, so to speak, to where you were searched, a matter of a few hundred yards, and you were searched in a field. Then you say you were marched off again from there, then you struck a road. Does that help you to place it on the map? Was the road running in an east/west direction or north to south, can you remember that? (Witness indicates on the map).

COURT ORDERLY: He is pointing down the road to the bottom left hand corner, Sir.

MR. FIELD FISHER. In which general direction is the road running?

COURT ORDERLY: East/west, Sir.

MR. FIELD FISHER: Well, having got as far as that, do you think you can see it on the map? If you cannot be sure, let us not press you about it.

A. No, I cannot be sure where it is on the map.

Q. Very well. At any rate it was a road that you reached which was running in a general easterly/westerly direction?

A. Yes.

Q. Was it a road you had been along yourself the previous day, or during the course of the battle, can you remember?

A. No, I cannot remember.

Q. What sort of road was it, quite a small one or a main road or what?

A. I should say it was a second class road.

Q. A second class minor road, it had hedges ditches or anything?

A. I think there was a ditch on the left hand side.

Q. When you got on to this road, did you continue marching along it or did you halt and cross it, or what did you do?

A. When we came off the field and on to the road we turned left.

Q. Yes? Did you see any transport of any sort on the road?

A. Yes there was quite a lot of German lorries and German soldiers marching.

Q. And where was the transport, on the other side of the road from you or did you have to go to the other side of the road to pass it?

A. That was on the right hand side of the road.

Q. So you were marching along the left hand side of the road?

A. Yes

Q. And if you then turned left on to this road, I take it you were marching in a west/east direction?

A. Yes I think we were.

Q. What was the next thing that happened when you found yourselves on the road?

A. We were walking and then we halted.

Q. Did you walk far before you halted?

A. Not a very great distance, I think, not more than a hundred yards.

Q. About a hundred yards and then you halted. Still on the left hand side of the road?

A. Still on the left hand side of the road, yes.

Q. Were you then in an orderly marching column, or were you straggling out?

A. We were in an orderly column, so far as I could judge.

Q. About how far from the front of the column were you, half way along, or a quarter, or where?

A. I judged I was about half way.

Q. Where did you have your hands at this time?

A. Behind our heads.

Q. All of you?

A. All those who were able, unless they were wounded in the arms.

Q. Did you see any other ill treatments while you were marching that short distance along the road or while you halted?

A. Yes I personally got struck in the ribs, and I also saw some of my other comrades hit with fists and rifle butts.

Q. There is one question I should like to ask you – when you were searched or at any time, were you questioned, interrogated in any way, or did you see anybody else interrogated?

A. I was asked by the German who searched me what regiment I belonged to, and I would not answer him.

Q. Was that all you were asked?

A. That was all I was asked.

Q. There was no official interrogation of you or any of the other prisoners?

A. Not as far as I could see.

Q. Did you at that time have any inkling of what was going to happen?

A. No I did not.

Q. Had any indication been given to you by any of the Germans as to what was going to happen?

A. No, not to me anyway.

Q. Did you hear them say anything to anyone else?

A. No; I could not understand German, but our battalion commander asked the Germans if we were going to be shot and they said “No”; then we asked our battalion commander if we were going to be shot and he said: “No, they dare not do that”

Q. How would you describe the temper of the German soldiers at this time, generally speaking?

A. Very devilish, very bad.

Q. Now we have reached the stage where you have halted on the road. What was the next thing that happened then?

A. We went along a little further and I think we had another little halt.

Q. And then?

A. Then I think we had two or three halts from coming on the road before coming to this farmhouse.

Q. You reached some sort of farmhouse; as you were marching along the road, was that on the right hand side of the road or on the left?

A. That was on our right hand side as we just turned round; I think there was a small gateway.

Q. I want you to visualise that you are marching down the road towards me; you have not started to turn anywhere; was the farm lying on that side of the road (indicating) or on that side? On the right or on the left?

A. My right.

Q. On your right hand side. Did you notice a field or anything like that on the right hand side of the road, before you came to the house, the farm?

A. No, I did not.

Q. Now you mentioned a gateway. Was this on the same side of the road as the farm or the other side?

A. That was on the same side as the farm.

Q. You mentioned turning – did you halt again anywhere near this farm before you turned anywhere, or did you just march straight to wherever you went?

A. I think we halted just before we got to the gate.

At this point in the cross examination, the surrender and aftermath (treatment) is complete and the questionning continues as O'Callaghan turns with the column through the gateway to the scene of the massacre. See massacre presently under construction.

Pooleys Affidavit (This part of the affidavit begins at the surrender and ends at the gateway of Louis Creton's Farm).

The first attempt to surrender was made by three men who walked into the open displaying a white cloth. They immediately came under heavy machine gun fire. The second attempt was then made by all of us running out into the open with our hands in the air. No further fire came from the enemy who stood up and cheered and a German officer ordered us to come forward with our hands in the air. No further fire came from the enemy who stood up and cheered and a German Officer ordered us to come forward with our hands in the air. We were lined up and searched, our helmets were struck from our heads and our equipment and gas marks were forcibly removed.

We had no weapons with us as these had been destroyed before we surrendered. Not one of us to my knowledge still possessed a weapon when we were searched by the Germans. We were told be an English speaking NCO that any wounded could sit down, whereupon some of us did. I was one of those (I had been hit in the left arm and right hip, but not seriously wounded). But no sooner had I sat down then I received a brutal kick in the ribs from a German soldier and was ordered to stand up. During the march which then took place several of us were struck because we did not answer questions or were not quick enough in obeying the orders of the Germans which naturally were unintelligible to us. During tis our wounded were being brought out of the farm house by our own stretcher bearers, but I do not know where they were taken.

After some 15 minutes we were ordered to form up on the road with our hands clasped behind the backs of our heads. During the process some of us were struck with rifle butts while standing in the ranks. The guards who did this were not reprimanded by their officers or NCOs. While we were standing there our numbers must have swollen by the addition of other prisoners because when I turned round I could see that the column had lengthened. I do not know where these additional men came from. At this time I estimate the number of prisoners in the column to have been 65 at the very least. We were then ordered to march along the road, all the time being struck and cuffed by the guards and any other Germans passing us. Our direction at this time appeared to be westerly across a road leading to LE PARADIS until we came in the vicinity of another farm house with a field adjoining it on the western side.

We halted on the road for 2 or 3 minutes. During this time a German took from my pocket a packet of cigarettes and when I turned to look at him he struck me with his rifle knocking me through the ranks. An unbroken line of German transport was standing on the right hand side of the road facing us.

We were then ordered to march again and it was at this moment I saw what had been prepared for us.

Pooley’s Cross Examination (This is taken from the time just before the surrender at battalion Headquarters Duriez Farm. Pooley is cross examined by the prosecution counsel Mr T. Field-Fisher).

Q. What was the approximate strength, do you suppose, of the remnants of the Norfolks which were holding out there?

A. I should say about 45.

Q. That is in the neighbourhood of the house in question.

A. Yes

Q. And who was commanding these remnants?

A. Major Ryder was the Colonel, Sir.

Q. What was the ammunition position by about the end of the morning of the 27th May?

A. We only had small arms ammunition left, we had no mortar ammunition and we had very little small arms stuff at all.

Q. What did Major Ryder decide to do?

A. Major Ryder suggested that we had performed everything which we had been asked to do and he could therefore see no further object in resisting any longer and thus wasting more lives.

Q. So was in fact an attempt to surrender made?

A. Yes.

Q. How was that done?

A. Three men went out from the house, through an outhouse door, holding a piece of white material. They immediately came under heavy m/g fire.

Q. Were they shot down?

A. They were shot down.

Q. Were they armed when they went out with this piece of white material?

A. No, they had left their arms in the outhouse.

Q. And was another attempt to surrender then made?

A. Yes.

Q. How was that done?

A. By everybody who was in a position to walk, walking out from the building with their hands raised.

Q. And did the people who came out thus, come under any fire or not, at that time?

A. At first, when we came out, before our intention was clear to the enemy, but I believe when our intention was clear to them the fire ceased.

Q. You said “all those who were able to walk”- did you leave many wounded at that time?

A. From my own knowledge, we had a good few wounded in the cellar; the exact number, I do not know.

Q. They were in the cellar of battalion headquarters?

A. Yes.

Q. And what about the people who came out to surrender, were they all, completely fit and whole men, or were some of them walking wounded?

A. Some of them were wounded, I was one of them.

Q. How was the surrender accepted by the Germans?

A. When the fire ceased, the enemy stood up from their positions and shouted and cheered.

Q. About how far from your last position at battalion headquarters do you suppose the advance German troops were?

A. Between 300 and 400 yards

Q. And from what direction were they attacking? Would you show on the map? Where they coming from the southerly, westerly, northerly or which direction?

MR. INTERPRETER: Do you want the witness to indicate with an arrow, Sir?

MR. FIELD FISHER: Yes the general direction of the German attack, the troops to whom they surrendered.

(The witness marks the position on the Map. Exhibit No. 1, and it is shown to the court). (The direction indicated is west to east).

MR FIELD FISHER:

Q. When the surrender was accepted by the Germans, what was the next thing that took place?

A. We were assembled in a field; our equipment was taken from us, including our gas masks, our helmets were struck from our heads; we were searched, all our clothing, but nothing was taken from us. It seemed to be a very perfunctory search, in my case.

Q. It did not really look as if they were searching for anything?

A. No, it did not seem that they were searching for anything in particular.

Q. Where did this search take place? Did you have to march to the place you were searched, or did it take place on the spot where the surrender was accepted?

A. It took place about 400 yards away, that would be the approximately the position of the enemy troops.

Q. About where their advance positions were?

A. Yes.

Q. And how did you get to that place, did you march along the roads or in the fields?

A. We walked along a field.

Q. Would that be on the north or south side of the road which is marked on the plan as Rue du Paradis?

A. It would be on the north side of the road.

Q. When all of you came out of battalion headquarters to surrender, did you have any arms in your hands at all?

A. No.

Q. What about the ammunition, had you got rid of what little you had?

A. All the remaining ammunition was thrown in the pond.

MR FIELD FISHER;

Q. Now we were just dealing with the time when you were searched, and certain ill-treatments which you described took place. Now after the march was concluded, what was the next thing that happened?

A. After standing around a while in the field – about half- an- hour I should say – we were ordered to form up on the road.

Q. That would be the road to the south, the Rue du Paradis, which is marked on the plan?

A. Yes.

Q. What sort of formation were you formed up in? Were you in threes?

A. We were formed up in threes with our hands clasped on our heads.

Q. Did anything happen to you while you were being formed up? Did any other ill treatments take place, or anything like that?

A. The guards were walking up and down the column. Anybody who was speaking or moving or looking round would be struck. I myself was struck be a German soldier with his rifle. He took 20 cigarettes out of my pocket. I turned and looked at him; he struck me with his rifle and knocked me through the ranks.

Q. What did he strike you with?

A. His rifle butt.

Q. On what part of your body?

A. The left side of my face.

Q. Did he do damage to you?

A. He knocked two of my teeth out and loosened others.

Q. Did you see that guard or any of the other guards reprimanded by any senior officer or N.C.O.?

A.The German soldiers seemed to be out of control. Nobody reprimanded them.

Q. When you formed up on the road, were there still about 40 to 60 of you, or more of you?

A. There were more when we were formed up on the road than I had previously seen in the Battalion H.Q.

Q. Did you see any German transport on the road?

A. Yes. There was a stationary column of German transport on the right hand side of the road facing us.

Q. And were you then ordered to march?

A. Yes we received then order to march.

Q. Did you see who gave the order to march, or did you hear where it came from?

A. I don’t know who issued the order. I simply received it from a German soldier standing by.

Q. While you were marching, did any ill-treatment take place?

A. We were prodded, but I did not notice anything outstanding at that time.

Q. And then did you come to a gate leading into a farmyard?

A. Yes. We halted on the road about 15 yards from the entrance to a field.

Q. I would like you to look at the map please, and indicate you can where this farmyard with the gate was.

(Witness indicates the point on the map with a pencil mark)

Q. You have marked a spot very near where there is a small black dot with a little cross above it, which is a shrine, I think you will see from the legend of the map. Do you remember that shrine at the time?

A. Yes. I saw that. It is the usual thing which you see in France dotted along the roads.

Q. Now, the entrance to this farm, the gate, was that gate directly off the Rue du Paradis.

A. Yes

Q. It gave on to the road?

A. It gave on to the road, yes.

Q. I want you to look at the rest of these photographs. (Photographs shown to the witness) Now, do you recognise the place represented by the other photographs – not the top one you have already identified, but the others on that page and on the other page?

A. Yes.

Q. Is that the place where what you are going to describe took place?

A. That is the place.

THE JUDGE ADVOCATE: Which photograph is that?

Mr Field FISHER: That is all the photographs, sir, except under 1. They are all of the same place taken from different viewpoints, and I think on the first page of the photographs there is a gateway shown into a field looking on a little road. (To witness) Is that the gateway in question?

A. That is the gateway in question

Q. One point I would just like to make. Have you visited tis village since the war?

A. Yes. I went over there in September 1946.

Q. And from your memory and from your reconstruction of it when you were over since the war, are you now quite sure of the identity of the place?

A. Absolutely.

At this point in the cross examination, the surrender and aftermath (treatment), is complete and the questioning continues as Pooley turns with the column through the gateway to the scene of the massacre. See under massacre (under construction).

The Surrender at the cow barn described in Cyril Jolly’s book The Vengeance of Private Pooley

This is extremely important as Cyril Jolly was fortunate to interview the two witnesses to the massacre. The following extract is produced by kind permission of the Jolly family.

The C.O. waited for a moment then said….”No….there’s little we can do”

There followed a long, tense pause, then the C.O. said, “Men, I call on you to surrender. Sergeant-Major get a towel and tie it to a rifle.”

Someone rummaged in a corner among some kit and brought out a towel, not freshly laundered, not unsoiled, but a white towel, the symbol of defeat. A Platoon Sergeant- Major fasted it to a rifle then moved to the backdoor of the cowshed, opposite the one they had entered. It opened onto a meadow, and one hundred and fifty yards away the Germans were firing from ditches and banks. The Sergeant thrust the rifle and towel through the slightly opened upper half of the door and held it thus for two or three minutes. The firing stopped.

“Open the Door” commanded the C.O.

“Follow me” said the Platoon Sergeant-Major holding the rifle aloft with the faintly fluttering flag. Then he went out, five or six men at his heels. He had not gone ten paces before a machine-gun opened fire on them and the Platoon Sergeant-Major and three or four men fell shouting and groaning. The rest of the men in the open rushed back and tried to get into the cow-house but many of those pressing behind, inside, not realising what had happened, did not give ground. For a moment it seemed that the men in the front would panic, but an officer rapped out an order and the door was closed. Again the firing ceased. Five more minute’s passed; then it was decided to make another attempt. An officer shouted “We’re coming out now.” Then again the towel was put out and with hands above their heads the men filed out – five, six, seven, eight. Pooley was among the first. Suddenly from behind a long bank and in ditches the Germans stood up, whooping triumphantly, waving their rifles excitedly.

Editor's Note

Looking through our records we believe that the Platoon Sergeant- Major who led the first surrender attempt may have been PSM Jack Whitlam who was positively identified upon exhumation after the massacre. In Bob Brown’s memoirs the following was noted.

This was now the middle of the afternoon. CSM Whitlam came round with the rum jar and said: "We might as well have this before the Jerries get it. " I had nearly half a mug and couldn't see for a while as the water streamed out of my eyes."

Surrender Three - The Ditch Surrender

Photographs courtesy of John Head. Special escape route map courtesy of Bob Brown and his daughter Vivienne Roberts.

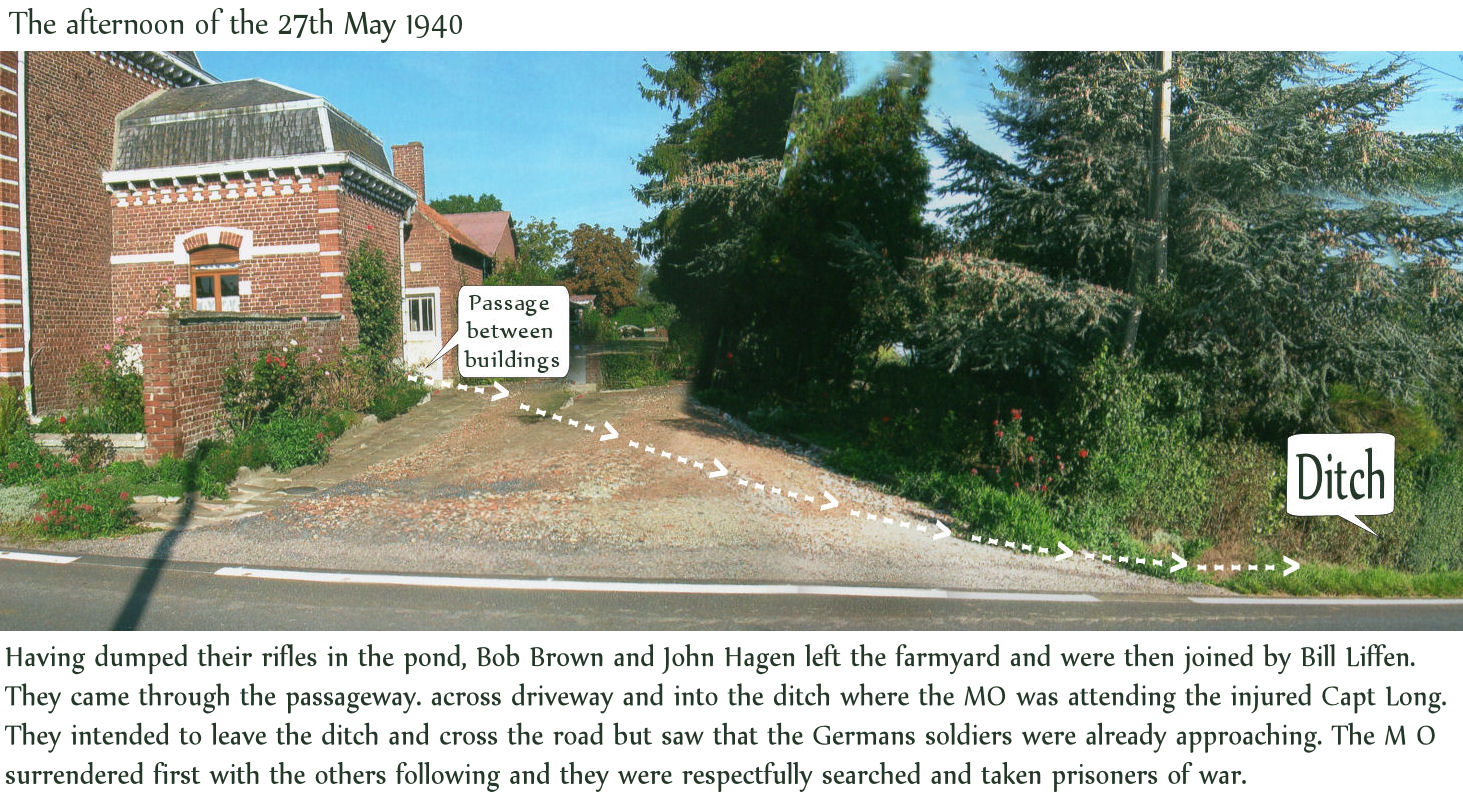

Escaping from the farmhouse several of the 2nd Battalion The Royal Norfolks dived into a ditch. Our photographs show the farm taken in the past few years with the ditch situated on the far right. Immediately above is a depiction of the route to the ditch taken by the soldiers and we are grateful to Bob Brown and his daughter Vivienne Roberts for their hard work in constructing this image and allowing us to use it.

Capt. Long described the action as follows:

“At 17.15 Hours I came to my senses outside the farm building I was lying in a ditch and two of my men pulled me from the ditch. Around were Germans with Tommy Guns”

Captain Hastings' diary notes report as follows:

"Woodward (believed to be Lieutenant John Woodwark- editor) and I get to a ditch and are later joined by others. We were not well informed about what was going on around us, but this was comparatively unimportant against orders to stand to the "last man and the last round". Virtually we did this, although it is true there were probably a few unexpended rounds in the magazines of some of the rifles and I had six rounds in my pistol which I did not fire; but there was nothing whatever for the Bren guns. Situated as we were, with everything shelled out and now in flames, our only cover, a road side ditch pointing the wrong way, our last chance of doing anything more to the enemy was gone. I was the senior officer of the party and I accepted the responsibility for surrendering. Nobody liked it.

"I myself was unwounded. If the reader wishes to think of something unutterably humiliating he may try to imagine my feelings I will not describe them to him. I walked down the road with the towel held high above my head but my eyes were naturally upon the ground. The muzzle of a Tommy gun was poked at me. The bloody thing could go off for all I cared. I did not look at the face of the soldier who held it, nor at the one took away my revolver. I did not see who snatched the field glasses from the strap around my neck, nor did I care who was the owner of the pair of hands that went through my haversack. If there was a horrible grin of triumph on the faces of these men I did not see it. We went on like a funeral procession.

Bob Brown recalls:

When we dropped into the ditch we found Adjt. (Captain Charles Long – editor) and the MO (Lieutenant David Draffin –editor) were there. Peering over the top of the ditch ready to get away, we found we were too late, the enemy was already coming up the road. John took aim with his rifle but the Adjt. said "Don't fire Hagan." If he had they would have just opened up and killed us all. The MO (Lieutenant David Draffin - editor) got out first so they could see his Red Cross. There were loud shouts and cries of "Hande Hock." We helped the Adjt. out as he was wounded and, not understanding German, put our hands up.

Bob Brown also recalls in correspondence with us that he and John Hagan entered the ditch together with Bill Liffen (often incorrectly referred to as Bill Levin in several writings and reports).

Richard Lane author of ‘Last Stand at Le Paradis’ summarises the event as follows which is produced by kind permission of Debbi Lane, Richard’s widow:

At about the time Major Ryder Surrendered, Captain Long regained consciousness. He was lying in a ditch which ran beside the road on the southern side of the farmhouse and he said that the time was 17.15. Lieutenant Draffin, the Medical Officer, was there, so too was Captain Hastings and two or three other men. A white towel was produced and Hastings held it above his head until the firing ceased.

Editor's Note

Looking through all records we feel the surrender party in the ditch comprised of : Captain Robert Hastings, Captain Charles Long, Lieutenant John Woodwark, Lieutenant David Draffin, Privates Bob Brown, John Hagan and Bill Liffen.

Capt. Long described the action as follows:

“At 17.15 Hours I came to my senses outside the farm building I was lying in a ditch and two of my men pulled me from the ditch. Around were Germans with Tommy Guns”

Captain Hastings' diary notes report as follows:

"Woodward (believed to be Lieutenant John Woodwark- editor) and I get to a ditch and are later joined by others. We were not well informed about what was going on around us, but this was comparatively unimportant against orders to stand to the "last man and the last round". Virtually we did this, although it is true there were probably a few unexpended rounds in the magazines of some of the rifles and I had six rounds in my pistol which I did not fire; but there was nothing whatever for the Bren guns. Situated as we were, with everything shelled out and now in flames, our only cover, a road side ditch pointing the wrong way, our last chance of doing anything more to the enemy was gone. I was the senior officer of the party and I accepted the responsibility for surrendering. Nobody liked it.

"I myself was unwounded. If the reader wishes to think of something unutterably humiliating he may try to imagine my feelings I will not describe them to him. I walked down the road with the towel held high above my head but my eyes were naturally upon the ground. The muzzle of a Tommy gun was poked at me. The bloody thing could go off for all I cared. I did not look at the face of the soldier who held it, nor at the one took away my revolver. I did not see who snatched the field glasses from the strap around my neck, nor did I care who was the owner of the pair of hands that went through my haversack. If there was a horrible grin of triumph on the faces of these men I did not see it. We went on like a funeral procession.

Bob Brown recalls:

When we dropped into the ditch we found Adjt. (Captain Charles Long – editor) and the MO (Lieutenant David Draffin –editor) were there. Peering over the top of the ditch ready to get away, we found we were too late, the enemy was already coming up the road. John took aim with his rifle but the Adjt. said "Don't fire Hagan." If he had they would have just opened up and killed us all. The MO (Lieutenant David Draffin - editor) got out first so they could see his Red Cross. There were loud shouts and cries of "Hande Hock." We helped the Adjt. out as he was wounded and, not understanding German, put our hands up.

Bob Brown also recalls in correspondence with us that he and John Hagan entered the ditch together with Bill Liffen (often incorrectly referred to as Bill Levin in several writings and reports).

Richard Lane author of ‘Last Stand at Le Paradis’ summarises the event as follows which is produced by kind permission of Debbi Lane, Richard’s widow:

At about the time Major Ryder Surrendered, Captain Long regained consciousness. He was lying in a ditch which ran beside the road on the southern side of the farmhouse and he said that the time was 17.15. Lieutenant Draffin, the Medical Officer, was there, so too was Captain Hastings and two or three other men. A white towel was produced and Hastings held it above his head until the firing ceased.

Editor's Note

Looking through all records we feel the surrender party in the ditch comprised of : Captain Robert Hastings, Captain Charles Long, Lieutenant John Woodwark, Lieutenant David Draffin, Privates Bob Brown, John Hagan and Bill Liffen.