Narrative and Papers of Maj R. J. Hastings attached to second battalion Royal Norfolk Regiment 1940. Part Two - From 27th May, 1940, to Prisoner of War Camp.

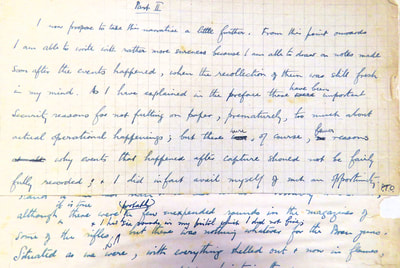

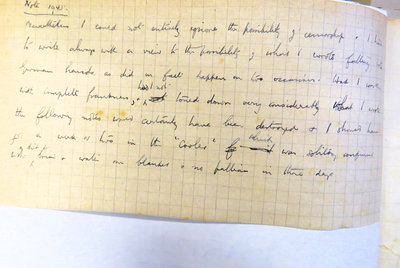

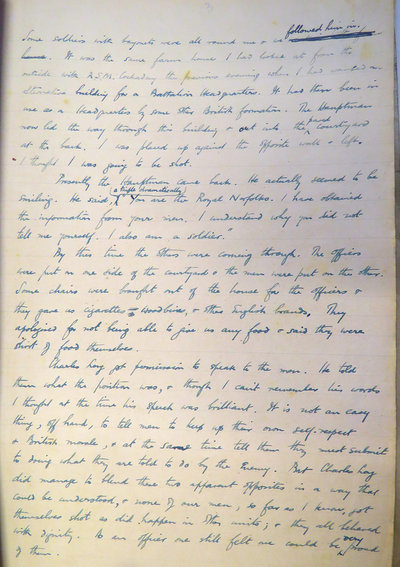

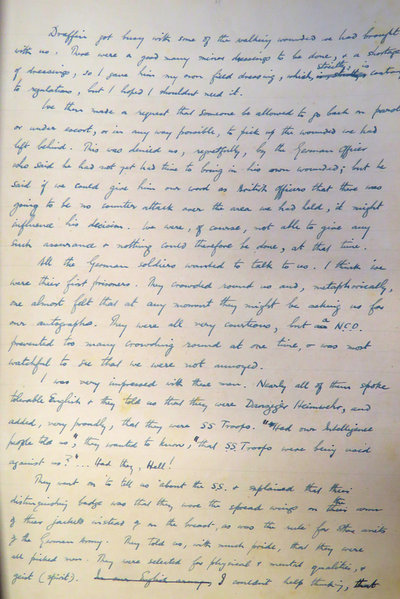

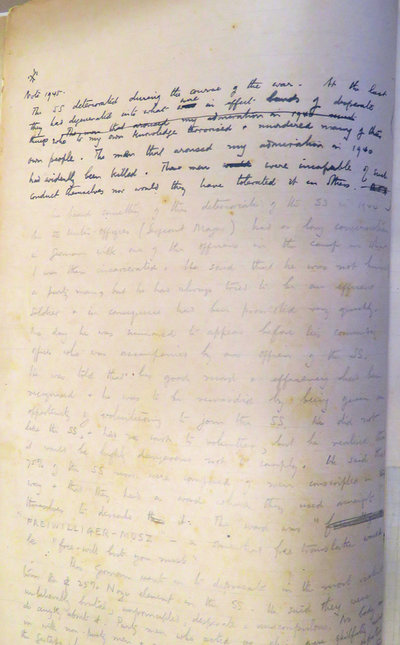

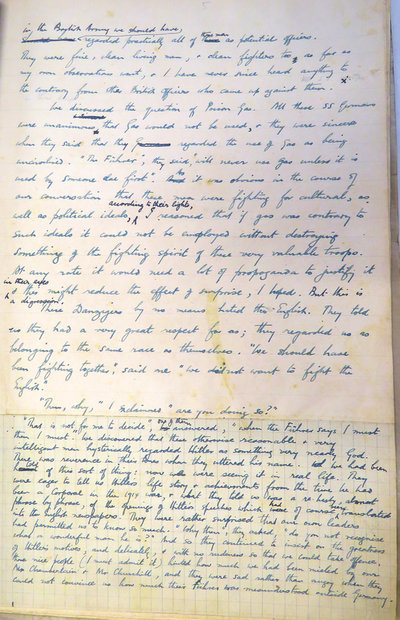

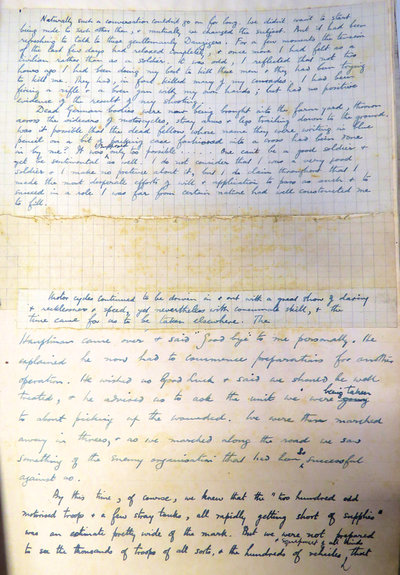

Examples of the original narratives are shown above.

Hastings Narrative Part Two

Preface

I now proposed to take this narrative a little further. From this point onwards I'm able to write with rather more sureness because I am able to draw on notes made soon after the events happened, when the recollection of them was still fresh in my mind. So I have explained in the preface, there have been important security reasons for not putting on paper, prematurely, too much about actual operational happenings; but there were, of course, fewer reasons why events that happened after capture should not be fairly fully recorded; and I did in fact avail myself of such an opportunity. Nevertheless I could not entirely ignore the possibility of censorship. I had to write always with a view to the possibility of what I wrote falling into German hands as did in fact happen on two occasions. Had I written with complete frankness and, had I not toned down very considerably what I wrote, the following notes would certainly have been destroyed and I should have got a week or two in the "cooler" which was solitary confinement with a diet of bran and water, one blanket and no palliasse in those days.

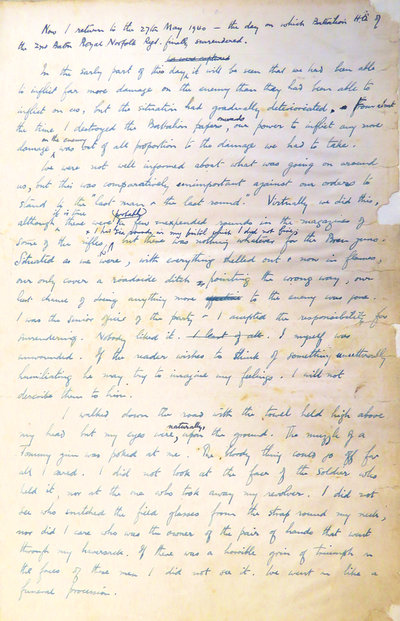

Now I return to the 27 May 1940- the day on which Battalion Headquarters of the 2nd Battalion Royal Norfolk regiments finally surrendered.

In the early part of the day it will be seen that we had been able to inflict far more damage on the enemy than they had been able to inflict on us, but the situation had gradually deteriorated. From the time I destroyed the Battalion papers onwards, our power to inflict any more damage on the enemy was out of all proportion to the damage we had to take.

We were not well informed about what was going on around us, but this was comparatively unimportant against orders to stand to the "last man and the last round". Virtually we did this, although it is true there were probably a few unexpended rounds in the magazines of some of the rifles and I had six rounds in my pistol which I did not fire; but there was nothing whatever for the Bren guns. Situated as we were, with everything shelled out and now in flames, our only cover, a road side ditch pointing the wrong way, our last chance of doing anything more to the enemy was gone. I was the senior officer of the party and I accepted the responsibility for surrendering. Nobody liked it. I myself was unwounded. If the reader wishes to think of something unutterably humiliating he may try to imagine my feelings. I will not describe them to him.

I walked down the road with the towel held high above my head but my eyes were naturally upon the ground. The muzzle of a Tommy gun was poked at me. The bloody thing could go off for all I cared. I did not look at the face of the soldier who held it, nor at the one took away my revolver. I did not see who snatched the field glasses from the strap around my neck, nor did I care who was the owner of the pair of hands that went through my haversack. If there was a horrible grin of triumph on the faces of these men I did not see it. We went on like a funeral procession.

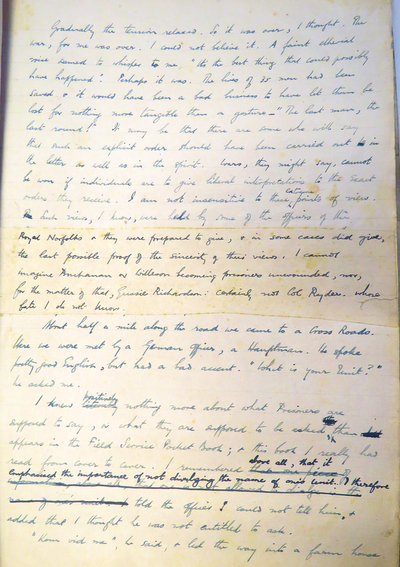

Gradually the tension relaxed. So it was over, I thought. The war for me was over. I could not believe it. A feint if etherial voice seemed to whisper to me, "it's the best thing that could possibly have happened". Perhaps it was. The lives of 35 men had been saved and it would have been a bad business to have let them be lost for nothing more tangible than a gesture - "The last man, the last round!" It may be that there are some who will say that such an explicit order should have been carried out in the letter as well as in the spirit. Wars, they might say, cannot be won if individuals are to give liberal interpretations to the exact orders they receive. I am not insensitive to these extreme points of view. Such views, I know, were held by some of the officers of the Royal Norfolks and they were prepared to give, and in some cases did give, the last possible proof of the sincerity of their views. I cannot imagine Buchanan or Willeson becoming prisoners unwounded, nor, for the matter of that Guasie Richardson: certainly not Colonel Ryder whose fate I do not know.

About half a mile long road we came to a crossroads. There we were met by a German officer, a Hauptmann. He spoke pretty good English, but had a bad accent. "What is your unit?" He asked me.

I knew positively nothing more about what prisoners are supposed to say, or what they are supposed to be asked other than that which appears in the field service book: and this book I really had read from cover to cover. I remembered above all, that it emphasised the importance of not divulging the name of one's unit. I therefore told the officer I could not tell him and added that I thought he was not entitled to ask.

"Kom vid me", he said, and led the way into a farmhouse. Some soldiers with bayonets were all round me and we followed him in. It was the same farmhouse I had looked at from the outside with RSM Cockaday the previous evening when I had wanted an alternative building for a Battalion headquarters. It had then been in use as a headquarters by some other British formation. The Hauptmann now led the way through this building and out into the paved courtyard at the back. I was placed up against the opposite wall and left. I thought I was going to be shot.

Presently the Hauptmann came back. He actually seemed to be smiling. He said, a trifle dramatically, "You are the Royal Norfolks. I have obtained information from your men. I understand why you did not tell me yourself. I also am a soldier".

By this time the others were coming through. The officers were put on one side of the courtyard and the men were put on the other. Some chairs were brought out of the house for the officers and they gave us cigarettes - Woodbines and other English brands. They apologised for not being able to give us any food and said they were short of food themselves.

Charles Long got permission to speak to the men. He told them what the position was and though I can't remember his words I thought at the time his speech was brilliant. It is not an easy thing, offhand, to tell men to keep up their own self respect and British morale and at the same time tell them they must submit to doing what they are told to do by the enemy. But Charles Long did manage to blend these two apparent opposites in a way that could be understood and none of our men, so far as I know, got themselves shot as did happen in other units: and they all behaved with dignity. As an officer one still felt one could be very proud of them.

Draffin got busy with some of the walking wounded we had brought with us. There were a good many minor dressings to be done and a shortage of dressings, so I gave him my own field dressing which strictly is contrary to regulations, but I hoped I shouldn't need it.

We then made a request that someone be allowed to go back on parol or under escort, walking any way possible, to pick up the wounded we had left behind. This was denied us, regretfully, by the German officer who said he had not yet had time to bring in his own wounded; but he said if we could give him our word as British officers that there was going to be no counter-attack over the area we had held, it might influence his decision. We were, of course, not able to give any such assurance nothing could therefore be done at that time.

All the German soldiers wanted to talk to us. I think we were their first prisoners. They crowded round us and, metaphorically, one almost felt that at any moment they might be asking us for our autographs. They were all very courteous, but a NCO prevented too many crowding round at one time and was most watchful to see that we were not annoyed.

I was very impressed with these men. Nearly all of them spoke tolerable English and they told us that they were Danziger Heimwehr and added very proudly that they were SS troops. "Had our intelligence people told us", they wanted to know, "that SS troops were being used against us?".... Had they, Hell!

They went on to tell us about the SS and explained that their distinguishing badge, the spread wings, they wore on the arm of their jackets instead of on the breast, as was the rule for other units of the German army. They told us with much pride, that they were all picked men. They were selected for physical and mental qualities, and geist (spirit). I couldn't help thinking that in the British Army we should have regarded practically all of these men as potential officers. They were fine, clean living men, and clean fighters too as far as my own observations went, and I haven never since heard anything to the contrary from other British officers who came up against them. ****Note 1**

We discussed the question of poison gas. All these SS Germans were unanimous that gas would not be used and they were sincere when they said that they regarded the use of gas as being uncivilised. "The Fuhrer", they said, "will never use gas unless it is used by someone else first". As it was obvious in the course of our conversation that these men were fighting for cultural, as well as political ideals, according to their rights, I reasoned that if gas was contrary to such ideals it could not be employed without destroying something of the fighting spirit of these very valuable troops. At any rate it would need a lot of propaganda to justify it in their eyes and this might reduce the effect of surprise, I hoped. But this is a digression.

These Danzigers by no means hated the English. They told us they had a very great respect for us: they regarded us as belonging to the same race as themselves. "We should have been fighting together", said one "we did not want to fight the English".

Then why, I exclaimed are you doing so?

"That is not for me to decide", one of them answered, "when the Fuhrer says I must then I must". We discovered that these otherwise reasonable and very intelligent men hysterically regarded Hitler as something very nearly God. There was reverence in their tones when the uttered his name. We had been told of this sort of thing: now we were seeing it in real-life. They were eager to tell us Hitler's life story and achievements from the time he had been a Corporal in the 1914 war, and what they told us was a re-hash, almost phrase by phrase, of the openings of Hitler's speeches which had of course been translated into the English newspapers. They were rather surprised that our own leaders had permitted us to know so much. "Why then", they asked, "do you not recognise what a wonderful man he is?"And so they continued to insist on the greatness of Hitler's motives, and delicately, and with no rudeness so that we could take offence, these nice people (I must admit it) hinted how much we had been misled by our Mr Chamberlain and Mr Churchill and they were sad rather than angry when they could not convince us how much their Fuhrer was misunderstood outside Germany.

****Note 1 1945***

The SS deteriorated during the course of the war. At the last they had degenerated into what were in effect bands of desperate thugs who to my own knowledge terrorised and murdered many of their own people. The men that aroused my admiration in 1940 had evidently been killed. These men were incapable of such conduct themselves nor would they have tolerated it in others.

Naturally such a conversation couldn't go on for long. We didn't want to start being rude to each other then, and mutually we changed the subject. But it had been refreshing to talk to these gentlemanly Danzigers. For a few moments the tension of the last few days had relaxed completely and once more I had felt as a civilian rather than as a soldier. It was odd, I reflected that not two hours ago I had been doing my best to kill these men and they had been trying to kill me. They had in fact killed many of my comrades. I had been firing a rifle and a bren gun with my own hands, but had no positive evidence of the result of my shooting.

Dead German bodies were now being brought into the farmyard, thrown across the sidecars of motorcycles, stray arms and legs trailing down to the ground. Was it possible that the dead fellow whose name they were writing in blue pencil on a bit of packing case fashioned into a cross had been done in by me? It was I supposed only too possible. …......... one can't be a good soldier and yet be sentimental as well. I do not consider that I was a very good soldier and I make no pretense about it, but I do claim throughout that I made the most desperate efforts of will and application to pass as such and to succeed in a role I was far from certain nature had well constructed me to fill.

Motorcycles continued to be driven in and out with a great show of daring and recklessness and speed, yet nevertheless with consummate skill, and the time came for us to be taken elsewhere. The Hauptmann came over and said "goodbye" to me personally. He explained he now had to commence preparations for another operation. He wished us good luck and said we should be well treated and he advised us to ask the units we were being taken to about picking up the wounded. We were then marched away in threes and, as we marched along the road, we saw something of the enemy organisation that had been so successful against us.

By this time, of course, we knew that the two hundred odd motorised troops and a few stray tanks, all rapidly getting short of supplies, was an estimate pretty wide of the mark. But we were not prepared to see the thousands of troops of all sorts and the hundreds of vehicles and equipment of all kinds that everywhere choked the roads.

We shall probably have to wait till after the war to obtain a full general picture of what was happening at this time. Such extracts of Lord Gorts book as have been reprinted in the German press make no reference to the troops it was necessary to leave behind in their positions to cover the embarkation at Dunkirk. Had his book contained any such details I think the Germans would certainly have reprinted it in their newspapers. But it is probably contrary to public policy that too much thought should be directed to this aspect of the embarkation whilst the war is still on. Yet, if the reader reflects for a moment, he will once see that it was necessary for small forces to be deliberately sacrificed at different points to delay the enemy advance and gain time for the major evacuation to be arranged. I do not know the extent of the forces that had to be sacrificed for this purpose, but it is evident that the brigade of which we formed a part was employed for this purpose. The Brigade staff and Echelon B personnel in the Battalions were all that got away.

Since then there is no available information from British official sources, I propose to go to the other side of the picture, and draw my information from a German account of the campaign. The SS division that opposed us considered that we had offered a pretty stubborn resistance to their advance. I will quote from an article which appeared in the "Volkisber Beobachter" of the 16 January 1942. The title of the article was

“Heroic struggle of an SS Division

The Fuhrer decorated SS Gruppenfuhrer Eicke with the Ritterkreuz”

The article begins by giving some personal details about the commander of the force and then goes on to say:

The Commander, who meantime had been promoted Lieut General of the army SS, moved into France via Holland and Belgium with his motorised division. After many days of forced marches this division was able to take part in the tremendous battle of envelopment in Flanders. At Cambrai and Arras, on La Bassé Canal, near Le Cornet Malo and Paradis the young force gained its first military fame. By boldly launching a dashing attack, the commander with his division was able materially to support the operation aimed at cutting off the British. The British elite regiments, the Royal Scots, the Norfolks and others were unable to resist the drive. Then came the great pursuit, carrying them down to Lyons and then to Bordeaux.

The article then goes on to record some successes gained by this SS division later against the Russians and says "this division is particularly proud of the fact that Timoshenko in a special order of the day demanded the utter destruction of the SS division."

The remainder of the article is not relevant, but it is interesting to note that throughout the whole article only only two units are referred to by name, our own unit and the Royal Scots, we were both in the same Brigade. The places mentioned around La Bassée Canal were those held by us and I think we may accept it as a high compliment that this redoubtable SS division, which Timoshenko was later to consider so formidable, should have found our poor efforts to delay their progress worthy of recording in this way. After all, our strength had only been that of one Brigade, sadly reduced by casualties to only about half its former strength; as I have explained, we were at this time seriously exhausted and not far from the point of collapse. We had no prepared positions and everything was improvised; and the fact that we were able to hold up, for as long as we did, this picked force who had everything they wanted including absolute air superiority, always astounds me.

I now return to that part of my story where the SS troops had handed us over to some second line troops by whom we were being marched away in threes. ****

****I must correct Bob Hastings. This was the same unit which had captured us and was actually part of the same company. The quite decent captain who looked after at the first farm we went to turned up here again, and I persuaded him to let Draffin and myself with four men to return to the old Battalion Headquarters and search for wounded. He quite happily gave permission and sent one German soldier with us. Charles Long.

About a mile away we halted and rested. Our members were counted up and totalled 4 officers and 36 men. Not all of those were Norfolks as there were some stragglers of other units. The Germans made us take off our steel helmets and ordered us to throw them into a ditch. Whilst we were waiting, hatless, the party of Royal Scots Adam Gordon had been sent out to command earlier in the day, arrived and joined us. We were glad to see that Adam was safe. A Royal Scots Subaltern was also with the party. This officer annoyed one of the sentries and was struck with the butt of a rifle. The manner, and whole attitude of the troops now in charge of us, was far different from that of the courteous Danzigers. The combined party was then marched off and we were eventually halted outside a barn.

A German detachment was billeted for the night inside the barn. They threw out a little straw, but very, very little, and we were bedded down for the night in the open. It was very cold and to make matters worse it rained all night. We tried to sleep touching each other for warmth with a few strands of straw laid on top to keep off the rain. We were, of course, soon drenched to the skin, and so uncomfortable, that I am certain no one slept, however tired they were; but I must say I was glad to lie down and close my eyes. I tried counting numbers and all sorts of little expedients to distract my mind. Charles Long was furious. At the best of times he is a bad prisoner, but then, I think the wound in his head has made him slightly delirious. He got up and started calling the Germans "swine" and shouting abuse generally. We had great difficulty in pulling him down and getting him quiet. Otherwise he would probably have been shot. We had not been given any food and were pretty hungry, or we thought we were. We were to learn more about being really hungry later on. During the night, a German sentry who was guarding us gave us a small piece of his own chocolate which we broke up into very tiny pieces, and shared. Later he gave us a piece of his cake which also we split up. Fortunately the rain ceased as soon as it became light and soon the sun shone brightly. The heat of the sun assisted the heat of our own bodies and we were soon moderately dry.

The Germans told me there was a dead British soldier in the ditch opposite and said if I liked to bury him I could have some spades from the farm. I got four or five men to dig a grave which they did very expertly. I could not find the man's identity disc but got his pay book. One of our own men found a tin of tobacco in his pocket which he wanted to keep, but I wouldn't let him. I asked Adam Gordon to say what was necessary over the grave and he said "Our Father" and we stood round. I got a bit of wood from the Germans and some nails and we made a wooden cross and wrote his name and number on it in indelible pencil and put it up in the ground over his body.

We had to wait sometime before we moved off. Several German units passed us on foot and we saw a good many staff cars and vehicles and uniforms and manners that were of a kind unfamiliar to us. There were however, I was sorry to see, also a number of vehicles and items of equipment of a design that was only too familiar. The Germans had captured intact quite a lot of British things - not very much from us - and made good use of them. The chief items I noticed were British 15 cwt and 30 cwt vehicles and camouflaged ground sheets.

Some of the German units that passed on foot were intensely hostile to us. They jeered at us and shouted abuse, the finer points of which no doubt were lost to us through our ignorance of their language, and they spat in our direction. I do not know if there exists the counterpart of these men in all armies. I should imagine not. I have never seen anything like it in the British Army though I have at times heard of pretty tough things happening even there and I have not sat on some dozen or more courts martial for nothing; but I couldn't help feeling that this particular exhibition was rather more of an unconscious expression of poisonous propaganda fed to ignorant and ill formed minds, than an innate difference between Germans and English. Many others I know will not agree with me.*****

****re-reading my notes in 1945 with a closer knowledge of German character I find this. I also have come to change my views. But once again can it be said that the views of a liberated POW who has had to take some hard treatment including two big scale reprisals (viz being handcuffed and having one's tables and palliases removed) are likely to be impartial?

I now had to make a small decision, the rightness of which has troubled my mind often since. A German officer had ordered one of our men to get a grey 15 cwt truck started which had been captured. The German driver did not know how to do this himself. Our man had quite properly refused. The officer now came to me and, through an interpreter, said he would make it worse for us if his order to start the truck was not complied with. His attitude was extremely menacing and there was no doubt in my mind he meant what he said, so I told the man to get the truck going. Perhaps I was pretty weak to say this, perhaps I was taken off my guard, or possibly, again I may have done the right thing. As a prisoner one can't argue successfully with the wrong end of a Bren gun and, anyway, I think that the Germans could have got the truck going themselves in another few minutes. None of our prisoners were harmed. I hope no British lives elsewhere were lost as a consequence of this act.

Permission was now given for two officers and two men to go back to pick up wounded. Long and the doctor went. The remainder of the party marched to Locon.

It was a very slow march, for three or four men had to be carried on improvised stretchers. RSM Cockaday was one of them. We had been allowed to take some frames and a door from the farm buildings to serve as stretchers. During the journey a German soldier we passed made an entirely unprovoked attack on Woodwark. For absolutely no reason at all he rushed forward and struck Woodwark on the face. This was very bad for Woodwark and might have been serious for him, for he had been wounded in the neck and was covered with bandages. We were all nonplussed, but could do nothing. I am most anxious to be fair in this narrative, but I can find no excuse whatever for striking an obviously wounded man. Even the German soldier who is in charge of us was shocked. He could speak a very few words of English and managed to apologise for the act of his comrade. At a later stage of the march, after he had left us, he took the trouble to come back and tell us that the man had been punished by his officer. We were prisoners now and we were beginning to feel like prisoners are supposed to feel. We did not talk but marched on in silence.

We passed one or two dead civilians thrown into ditches at the sides of the road. One French peasant in his best velvet suit remains very clearly in my mind. We also saw a number of dead British soldiers. One party, I noticed especially, looked as if they had been caught by machine-gun fire as they emerged from a wood, the edge of which was about 10 yards behind them. The feet of some of them were bare and it looked as if their boots had been stolen. We did not know then how short of leather the Germans were. It began to rain again and continued to rain until we got to Locon.

At Locon we were put into a barn the floor of which was covered with straw. Still no food and we were a bit more hungry. There were many other British troops in the barn amongst them members of our own "C" company whose fate up to then we had not known about. They had been mopped up that morning and the company commander Maj. J.H. Elwes, had been killed in circumstances of great gallantry.

He had, I was told, personally led a bayonet attack against Tommy guns at short range and had been shot dead. I think about 50 men of his company were prisoners.

Adam and I were called over to the centre of the barn to be interrogated by a tall German officer who spoke fluent English in a, very loud, truculent bouncing way as so many Germans seemed to do. He had before him PSM Barrett and PSM Howitt of the 2nd Norfolks and CS M Kelly of the second Manchesters. I did not hear the beginning of the story but he was saying that certain articles of German equipment, including respirators, belonging to 3 German soldiers had been found in some buildings which he was alleging had been used by "C" company as a headquarters two days ago. The accusation was that the equipment belonged to German soldiers, who it was alleged, as we had no prisoners, had been murdered before we ourselves had been captured. The whole case appeared to turn on identifying the building in which the articles were found as being the same building that "C" company had occupied. If the case was proved, said the German officer, then these sergeant majors were to be shot. Each sergeant major, it appeared, had told the German what buildings had been used by our formations, but the German did not believe them. He now asked me if I would like to tell him where the HQ. of the company had been to which these warrant officers belonged, two nights ago. I was inclined to demur at first not being sure yet whether such information might still be of military value. He cut me short "Do you think I should come to you if I wanted military information? I should not waste my time questioning an officer, I should question your men". This very wordy German officer bragged a great deal more in this strain, but it was evident, with "C" company mopped up and the whole area now in German hands that there could be no military value in giving corroboration to the Sergeant Major's story. Asked if he would except my corroboration as evidence to acquit the sgt majors and he agreed that he would, as I had not been present when they made their statement and could not have known what they had said. I then drew a sketch map showing where "C" company had been the night before last and hoped for the best. It turned out not to be the place where the equipment had been found and the sergeant majors were acquitted and they were much relieved. They had looked pretty glum throughout this argument and I think they had good reason to be glum. It was rough justice and a pretty queer sort of trial and one didn't feel sure until it was over that the verdict would necessarily go the right way.

Long now rejoined us. He and Draffin had been back to our old headquarters and had found some wounded still alive and had disposed of them. Long's account of what he saw is not very good - the wound in his head, though not serious, was a nuisance. I had hoped to be able to hear Draffin's account, but the hands of this energetic little doctor were filled to overflowing by his cases and when we moved off he was kept back by the Germans to continue his work on the spot. We were still hungry. Long and Draffin had been fortunate enough to be given some lunch in a German officers mess. The last decent meal they were to have for a long time. Of the building that we had used as an HQ Long has told me since, that he remembers it chiefly as a confused heap of debris with parts of the burnt out walls of the house still standing.

We marched into Bethune and saw the extensive damage to that town that the German bombing had done. Our column was led by a very arrogant and noisy little German who stood up through the sunshine roof of a small car in which he was being driven. He had a little red disc on a short stick and this seemed to give him priority of movement on the road. First by waving the stick he could make all other traffic get out of his way. We couldn't help noticing that the Germans had traffic problems similar to ours and they did not appear to be able to handle them any better. If anything, I think their traffic control was worse on the whole. I don't think the red disc on the little stick improved matters much, for the German who had it was so pleased with the importance its position seemed to confer on him that he was apt to flash it about and inconvenience other traffic in an unjustifiable way.

We were all astounded by the numbers of vehicles and men that the Germans had got. We even saw some horse cavalry at one point though I am not sure whether we saw this here or at a place further on. Air superiority was complete. Not only did the Germans do everything they wished to do in daylight and took no pains to conceal any of their movements, but they could afford actually to advertise their activities to the air. Every German vehicle was brightly marked by large strips of red or yellow bunting tied over its roof. We were beginning to see many British vehicles decorated in this way. Far too many, I thought, had been allowed to fall into the hands of the enemy and I cannot help feeling that some of our units ought to have been more careful in this respect.

It was a relief to me at first to be marching behind somebody else whose duty it was to read the map, but this feeling of relief quickly turned to annoyance when I realised how many mistakes our guide was making. Each mistake he made involved us in extra marching and as we were so tired and hungry it was maddening. Eventually we got to Bethune Station, but not before our own little German had had to scream inquiringly at people on foot. We were not sure what the rank of this little man was. He seemed so important I thought he might be a colonel at the least, but when he dismounted in Bethune station yard where there was a group of officers to which he reported, he went through such a long and comic recital of saluting and bowing and bowing or saluting and continued to keep up his hand in a sort of abject salute during the whole of his conversation with them, that I am sure he could be nothing more important than a rather inferior NCO.

I do not know where our men were put at Bethune station. The officers were shoved into a hut in the goods yard where there was some straw. We got down to sleep straightaway. As our clothes were wet we woke up after a bit and burnt some straw in a brazier and I believe we found some coal. Once again we began to feel very hungry.

We now had one or two other officers with us. I remember Reggie Howarth of the Lancs Fusiliers was one, and while we were getting dry in front of the brazier the door was opened and a very wet and bedraggled kilted figure was R.....L..... of the Cameroons. He proceeded to take off his wet kilt and get it dry and any doubts I might have had up to that moment as to whether underclothing is a necessary ancillary to the Scottish National costume were dispelled. It was rather a fine kilt. He told us it had a history and had been worn in the 1914 war. It was later to attract a good deal of notice from the Germans, who never seemed to be tired of photographing it, for it was the only kilt in the early days of captivity, to be worn by a prisoner of war. Indeed so much of a novelty did it appear in their eyes that at our first permanent camp, Oflag VIIC, an artist came specially from Munich to paint a picture of it.

Before we left next morning we were given some un-sweetened black coffee or it may have been chicory, it was not much of a drink, and some biscuits in packets. The biscuits were good and were of French make. I am certain we only got this food because we yelled for it. We had started shouting "Food", "Essen", almost as soon as we woke up and kept up this cry persistently. The Germans were not unduly annoyed and a sentry came and told us politely he would see what could be done. The Germans appear to understand noise and to like it. They are not subtle. I stole a little aluminium cup, which was to serve many a useful purpose later. This was the first of a whole series of petty thefts which I and all other prisoners were later to commit and to take as a matter of course.

Honesty only existing among the thieves themselves. POWs do not steal from each other, though there have been notable exceptions even to that rule. We were conveyed in a lorry a distance of about 5 miles and fetched up in a factory where the raw material used was either flax or gun cotton. There was plenty of the stuff lying about and it was comfortable to lie on. We were put into the house of the resident manager which had of course been evacuated. Outside, in the grounds, and in the factory buildings, there were several thousand troops of different nationalities mixed together. There were British, French and French colonial troops, the latter with red hats or turbans looking very sinister with several days growth of black beard on their faces and also I think some Dutch. In fact the appearance of all ranks was unkempt and very horrible, for no one had had any opportunities for washing or shaving and many of the soldiers were looking ill. Eyes were shining and staring and in all faces one read the same dreadful story of hopelessness, gloom or bodily sickness. Sanitary arrangements were nil. Neither before or since have I seen anything so disgusting. It was a plague spot.

It was at this point that officers became finally separated from their men. Our men arrived on foot and were swallowed up in the crowd. The officers were kept to the manager's house. Here we met Dick Howe and Carbendale (G) of the Tanks; Colonel Stainer of the Lancs Fusiliers and his officers; also Padre Wingfield - Digby. We were able to spend French money by getting permission to walk to the front gate (this was granted without undue fuss) and negotiating through the bars with someone in the French crowd outside to make our purchases. Some wine was obtained in this way and also a good deal of money was lost as the messengers did not always return. We also wrote letters to our people at home telling them what had happened and these were collected by the Germans, but I have never heard that any of these letters reached their destination.

One amusing diversion was created by an officer called Brewster, of the Dorsets, who had found a black frock and a silk hat somewhere in the manager's home. These he proceeded to wear. He walked out amongst troops in the absurd outfit and the sheer incongruity of his appearance created endless laughter and the Germans didn't quite know how to take it. They made him give up the sable hat but for some reason or other allowed him to keep the frockcoat.

The night proved again to be cold. There was no artificial light and we slept, or rather we lay down, on the floor in the darkness and laid pressed together as close as possible and shivered. A bowl of black unsweetened ersatz coffee arrived when it was daylight and this we drank from cigarette tins or anything else we could find and at 5:30 am we left that place. It was the final break between officers and men. The men remained behind.

A short distance away some German troop carrying vehicles were waiting for us. We were evidently their return load back to Germany. These vehicles are superior to the equivalent vehicle in the British Army. They are similar in size to the British 3 tonner, they are driven by a diesel engine and they draw behind them a trailer of similar size. Planks of wood fitted across into slots on either side serve as seats. Each truck accommodated 25 persons and the trailers another 25, so that one driver could carry 50 men. These vehicles seemed to hold the road well and were capable of considerable speed. German drivers seem to be encouraged to drive fast and to drive in a way that we in the British Army would suppress on the grounds that it was reckless. We had many unpleasant shocks until we gradually came to feel that probably the driver did know what he was doing after all. I had previously observed with the Danzigers that stunt driving of motor cycles and sidecars seemed to be the order of the day and I'm not sure whether this is a bad thing. I am sure of this: if I had to be driven very fast from one place to another in an emergency I would sooner be sitting behind a German driver than an English one, though I have little doubt that it must have cost the German army a great deal of money in broken vehicles to train their drivers up to this standard of proficiency.

It was difficult to follow the route we took without maps which I guess we did not have. Doullous and St Pol were recognised, then a French officer sitting next to me told me we were near St Quentin then we went over the Belgian border to Narmur. We passed over a number of temporary bridges built by German engineers to replace those that had been demolished. I am not an expert in such work and therefore my opinion of it cannot be of much value, but I must say I was tremendously impressed.

French, Belgian and British officers were moved together in the truck I was in. No food was issued. The French had suitcases and all manner of things and possessions likely to be needed, including food. They ate their food but did not offer to share it and to make matters more unpleasant they were constantly demanding more than their rightful share of what room there was on the seats. Somebody, who also claimed to have some knowledge of the French army, said these were not a good type of French officer. He thought they were probably L. of C. Men.

We reached the delightful little Belgian holiday village of Beauraing about 6 pm and here we saw an encampment, containing prisoners in tens of thousands. They were mostly French. We were rather disheartened. These prisoners were set down on the ground in an enormous compound which had something of the appearance of the downs at Epsom on Derby Day. Sentries with Bren guns at frequent intervals were placed round the periphery. I have since spoken to a doctor who was working in this compound. He told me there were many sick and the only covered place for them to be was in some stables, the floor of which was several inches thick with old manure. Many prisoners died and a number were shot.

We passed this encampment by and were very glad to do so and marched to the other side of the village where there was a hotel standing in large grounds. The French officers were separated and put at the head of the column and we were all marched in here. This place too was chock a block with prisoners and after a bit it was decided that no more could be admitted. So we turned about and marched back the way we had come. This meant that all the French officers are now at the back of the column. We were led to a pleasant little infants' school on the outskirts of the town which was unoccupied. Just before we entered the gate, the Germans remembered that the French were not now in front, so we were halted, and the French were brought out and allowed to go in first and settle down in the best of what accommodation there was and, when they had done this, the rest of us were allowed to enter and make what we could of what was left.

This discrimination between British and French was of course a German move and we realised it as being such, and there would have been no bad feeling had the French shown even the slightest gesture of generosity or sympathy towards us, who, were after all their allies and in just the same predicament as themselves. No gesture of any such kind was offered. The French wanted to keep to themselves and for themselves. Perhaps they were as glad as we were, when later on we separated. I could not have been more glad and there is another thing that makes too close an intimacy with the French difficult. Their ideas of sanitation and ours are basically different.

In spite of its limitations, this little Belgian school was a pleasant interlude. We got some food here. Macaroni rice and potatoes stewed together in a field cooker. No one had any eating utensils; as regards containers, one or two had their mess tins, but most people had to use cigarette or tobacco tins. I was fortunate enough to pick up a nice white enamelled washing bowl. I got a good portion of stew in this, but there was more than enough to go around and we had second helpings and third helpings and eventually we all filled our stomachs. "Fingers," someone said "were made before forks". My own fingers I remember on this occasion were assisted by a piece of wood from a broken pencil box and personally I preferred it this way.

The floor of the school was tiled, but there were odd bits of carpet and one or two mattresses, but we had no blankets and again we were cold. Next morning we found some water in a tank and my tin bowl again did good service and several people washed in it. Brewster was still wearing his frockcoat and his appearance was now more comic than ever, for he had found some balls of coloured wool in a cupboard in the school and some knitting needles and it appeared that he was an accomplished knitter. Balls of wool now filled the pockets of the frockcoat from which brightly coloured strands silhouetted themselves across the dark cloth to an........ looking piece of work that was beginning to take shape between the knitting needles he was deftly....... with his hands. This was so ludicrous, that I am afraid it is beyond my power to describe it.

We got another meal of exactly the same stuff as the one we had the day before and, in the afternoon, we marched to the station, waited about for sometime and then marched back again. There was no train. Whilst we were standing about idly in the school playground there was a call for a doctor. Dr. X.. Was in our party but he took no notice whatever. The call was repeated and once again Dr. X ignored it. He told us he thought if he let it be known he was a doctor he might be kept back to work as such in a hospital and it might affect his chances of repatriation. So the call was unanswered. It may have been that it was only for something trivial, we never knew. We got still another meal and marched to the station once again in the evening. It was pleasant marching through the streets of Beauraing. If in future I should ever spend a holiday in the Ardennes I think I shall come to this town again.

We were in for another very uncomfortable time in German unupholstered rolling stock. We were very crowded and Adam Gordon and somebody else found they would be more comfortable on the luggage racks and someone else slept on the floor. I was slightly too large to attempt either with success. We were allowed to get out of the train but sanitation was possible because there there was a lavatory attached and it was found that the blank cheque forms from a Glyn Mills cheque-book could still serve a useful purpose.

The train stopped frequently both at stations and in between. At one halt some children on the side of the line gave us some sticks of raw rhubarb which was most welcome as we had once again become very hungry. And at one station, where we were held up a considerable time, we were addressed from the platform by a very pompous seemingly important local figure. He gave us a summary of the news of the last few days and claims that Germany now had all the channel ports. "History is about to repeat itself", he said "in five or six days time we shall invade England. It will be 1066 all over again". Someone asked if there was any chocolate in Germany. "No”, he said. “shocolate we have not got". Someone else asked whether we should be well treated. "Yes," he said, "you will be well treated - but a member of you will be shot". We asked why and he went on to say that it was because we had shot parachutists. Hitler had said that for each parachutist killed ten British prisoners would be shot. We didn't really believe much of this but it did rather cast gloom on the party for some time to come. I still think if Germany had been decisively successful just at this time, this and other threats might quite possibly have been carried out. Large red banners were being flown from the windows of every house so it was obvious something very big had happened. We didn't know what.

We arrived at Trier later in the day, we saw further multitudes of prisoners. They were mostly French and there was a large proportion of French coloured troops. There was one dead coloured man we passed by the side of the road. We supposed he had been shot by the sentries trying to break out of the ranks. The sentries showed no reluctance to shoot whenever they got an excuse. We marched out of the town and up a graded road to a high plateau which overlooked the town and was completely encircled by a ring of hills of equal height, anything from 5 to 10 miles away. It was the most impressive and beautiful site for a camp that could be imagined. There was a whole village of rough unpainted wooden buildings and a permanent well-built barracks of stone. We learnt that the huts had formed a camping place for the Hitler youth organisation.

We saw more thousands of prisoners and we wondered if there could be any French army left. We were, of course, utterly out of touch with current news. There were also many Dutch prisoners here. So we were in our ranks waiting to be told where to go, a familiar voice some distance away shouted "Bob! Bob Hastings." I turned and was delighted and surprised to see John Carr, a real old friend who lives in the same town in England as I do. We were both equally surprised to see the other, for neither of us knew the other had gone abroad. John Carr's unit, I knew, was untrained. I was now to learn that there were three divisions of untrained troops in France. They had been sent over for work in the back areas - digging etc. They were also practically unequipped, or such equipment as they did have, was largely last war stuff and obsolete. I got the number of John's hut and we arranged to meet later.

As it happened, however, the main compound was now full and the party I was with was taken out and put into the permanent barracks. Here we got comparatively comfortable beds, albeit they were of the three tier variety - one bed above the other and another on top of that. Yet I have never looked with such relish on a straw filled pallaise supported on wooden slats as I did then. I shall never look with relish on such things again for the two years unrelieved acquaintance with this brand of sleeping amenity which I have suffered since, as a prisoner, has done little to make me accustomed to it. **see note 2** It wouldn't be so bad if one had a soft pillow, which is I think even more important than the mattress itself.

**note 2**Note made in May 1945

I was wrong in saying I would never look with favour at these beds again. On January 14, 1945, our palliases were removed leaving nothing but the wooden slats. This reprisal also included the removal of the stools and tables and, as the odd 10% were all needed by the administrative staff, it meant for me that my bed had also become my chair. The weather was several degrees below zero at this time and there was only enough fuel to have the fire lighted for cooking purposes. Red X parcels had failed to arrive and the German rations were so meagre that no one cared to do their...?.. by wasting calories in walking outdoors and it was necessary to spend most of the day between blankets for warmth. Palliases etc.were returned in March and, though most of us had improvised substitutes with our surplus clothing and cardboard, we certainly were glad when our beds were re-constituted in the original way.

The next morning at Trier must have been a Sunday. I didn't know for I had long since lost all track of dates and the days of the week. Padre Wingfield - Digby said it was and held a little service in one of the rooms which we all attended. He preached a short sermon which I forget, but I remember the text: "Be still and know that I am God". Nothing at that time could have been more apt.

During the day, large flights of heavy bombers took off from a well concealed aerodrome nearby and passed over our heads flying very low, for the aerodrome was too near for them to have gained much altitude. They were heading in a westerly direction. Were our friends and relatives in England to see and hear these identical machines in a few hours time? It was a very unpleasant thing to think about.

The food at Trier was not bad. In fact it was the best scale of rations the Germans have ever provided us with. Breakfast: brown bread and jam. Dinner: soup. Tea: brown bread, cheese and butter. I saw John Carr once again before we left and he showed me a letter from his wife containing some home news that was interesting to me. This letter was dated a few days later than the last letter I had.

We left Trier in the evening and marched a roundabout way to the station. The local population lined the streets and photographed us and little boys ran along beside us poking fun. The older Germans were decent enough to refrain from such demonstrations: some of them looked grave and appeared to be genuinely sympathetic. We certainly presented a pretty disreputable appearance for there had been no facilities for washing and shaving for a long time and, now I come to think of it, I fancy I myself must have cut rather an absurd figure, for I had drawn a large wedge of cheese - the rations for our party - just before we left and there had not been time to cut it up and I was carrying it in my hand.

A Belgian private had been acting as an interpreter at Trier. He was a really delightful fellow and as clever and tactful in dealing with the Germans as with ourselves. Someone had discovered that in civil life he was a well known writer of books and plays, though I had not heard of his name before and do not remember it now. This Belgian had told us we were probably going to Mainz. The alternative place would be Limburg. Mainz proved to be correct and we arrived there the following morning. Same crowding. Same hard seats.

There had been a French General at Trier and he followed us to Mainz. Quite properly he had refused to march in the ranks with everyone else and demanded a conveyance to the station which had been provided. He was a tall, pale and a dignified figure and it was evident from his tense and worn expression that he was suffering great emotion. We saw him once or twice at Mainz and later we were to hear he had committed suicide.

We marched from the station at Mainz to the castle nearby which had been converted quite recently, it appeared, into a barracks. There were other prisoners already there but we were not allowed to speak to them or come in contact with them in any way. We spent the day lying about on the ground under a corrugated iron shelter; the French, who as usual had got there first, were jealously monopolising what few benches there were. A German officer told me that Mainz was only a transit camp, but it was evidently a very important centre. At one time I saw as many as four German generals talking together and walking up and down in the square. They looked very smart, these German generals, and could be identified by the broad crimson stripe down the sides of their breaches, as well as the other refinements in their uniform which other officers do not have. Food that day was bread and jam, ersatz coffee and, in the evening, soup. In the evening we slept over a stable on straw and we slept well.

There was water for washing in the morning, but out of all the British officers, several dozen of them, only one towel was forthcoming. This was so much shared that it could be used no more. No one had any soap and no one had a razor. A few tooth brushes there were, but these are legitimate private property. I wasn't fortunate enough to have one myself. The French, on the other hand, appeared to be well supplied with all they needed and, as usual, made no offer to share anything. I am certain the French had made up their minds in advance to let themselves become prisoners for not only did each one of them have a large suitcase,- some of them even had two! I do not blame the French for the preferential treatment they received at the hands of the Germans, for this obviously was not of their doing, but I do reproach them for the way they followed up these advantages. I do not think it will ever be possible for the British to work in very close co-operation with the French. The fundamental lack of understanding seems to be too deep-seated for friendship to survive the test of adversity, but I do sometimes wonder what the French think of us. Probably at this time they were thinking we were mugs not to have provided for our future comfort in the way they themselves had been at pains to do.

I am half ashamed of having made these little generalisations regarding French and British psychology for I have always thought such generalisations were a bad thing when they have been made by others. However, what I have written shall stand. One day perhaps it may be proved wrong and I shall be sorry for it and although, for the sake of the future of France, I sincerely hope that it may.

We got shower baths during the morning and made our first acquaintance with ersatz soap. It was like whitewash. We were shepherded into a delouser in batches of twenty. Our clothes were taken away and baked whilst we enjoyed the hot showers and afterwards stood about naked to get dry for there were still no towels and, while we were doing this, a man came along with a paintbrush in a little can of some strong smelling disinfectant oil and painted those parts of our bodies that he thought might still harbor lice. The bath had been grand. We came out of the bath house by another door and were now allowed to mix with the other prisoners who had also been done and were now separated from those who had not. I am bound to say that the measures taken by the Germans dealing with vermin have, throughout the whole of my captivity, been excellent. It is their boast: "There are no lice in Germany". This is not strictly true; but it is nearly so and the one request a prisoner of war can make and know that it will receive immediate attention is a request for disinfestation.

In the afternoon, the interrogation took place. The great thing about this occasion was that one got a cigarette out of it. Each officer in turn was called to a small comfortably furnished room in which there was a desk, some reference books, two comfortable chairs and a box of cigarettes on the table. The officer, who interrogated me was, I am certain a Jew. He was a foxy little man and he spoke extremely good English. He got up as I entered and settled me down comfortably in the chair opposite to him, offered me the customary cigarette which I was glad enough to take: then he settled down himself and the stage was all set for a pleasant easy conversation across his desk.

What part of England did I come from, he asked. Yes, he knew England very well. He liked the English and had many friends in England. Did I know Wales? A most beautiful place. He visited friends in Wales every year on his holidays. Betws-y-Coed. Did I know it?. What did I think Britain's attitude would be if France made a separate peace? Did I think Britain will be likely to make peace too? I pleaded I had been without reliable news for three weeks, which was true and I didn't know anything about this present situation. "Now suppose", he went on, "that France did make a separate peace, do you think Britain will be likely to make peace too? Suppose the German demands were light - the return of the former German colonies of course..... Perhaps the payment of a small indemnity to Germany to meet the cost of the war - that would only be fair, wouldn't it?"

He waited for me to say something. I wasn't interested enough to be drawn, so he put the question definitely. "What do you think Britain's reaction would be to that?" So I now had to say something. I said I thought there were some sort of agreements about it and it was usually a principle with my country to stand by their agreements whether it was to their immediate advantage or not.

Thinking over this interview afterwards, I was rather sorry I had been enticed into making this little thrust for it was intended as such and it is quite possible that the German won after all and that I had told him exactly what he was hoping to find out. He didn't win in the second round, however. He thought I had been attached to the Royal Norfolks to give them some instruction and he was most anxious to find out what it was. He put the usual questions to me about whether I had any experience in colonial administration which I understand were put to all officers and the interview terminated. It had lasted long enough for me to be able to take a second cigarette without too much of a show of bad manners.

I compared notes with other officers who had been interrogated and found, without exception, that they all felt they had scored heavily at the Germans' expense. They told me what they had been asked and what they had said of the little thrusts they had got over of which they were very proud. Adding together all I heard, I am now inclined to think it was a very clever piece of work on the part of the Germans who knew we would not talk about military matters but wanted to test our general feelings which they provoked us into showing in an indirect way. I know there are many who will consider this is altogether too subtle for the German mind, but they must remember that this interrogator was not a German. He was a very clever Jew. I know that if ever I have to undergo another such interview I shall pose as a complete idiot and be done with it.

After interrogation we were allowed to go to the Kantine. There were seven of us - Adam Gordon, Charles Long, Simpson, Johnny Woodward, McKinnon and Dr Barker and myself. We each put what little French money we had together in a common pool and Adam Gordon got into the long queue there was in front of the counter and made some purchases. We all became the owners of toothbrushes and there was enough money to acquire as common property, a comb, a razor, some hair oil and some ersatz shaving and toilet soap and also some cigarettes. Beer was on sale but our small funds would not run to it.

I was called out of the Kantine to fall in with a party of exactly 200 who were about to move off. We were each given 1/4 of a brown loaf and a piece of cheese and marched to the station. Adam Gordon, Charles Long and the others were left behind. Whilst we were waiting for the train the German officer in charge of our party tried to bring us up-to-date with the news. He told us about the evacuation at Dunkirk and said there was some very brave fighting taking place there which he admired, but he said that those of the BEF who had got away had to leave all their equipment and guns behind them. We didn't believe a word of it and said so. He went on to tell us the French radio stations still broadcasting news of successful counter attacks by General.......... which he maintained was fictitious, and concluded: "As you know gentlemen, General.......... is here in Mainz. You have seen him yourselves". Nothing would really convince us, however. Had we not heard all about German propaganda in England? But we began to have rather disturbing doubts.

The German officer told us we should be in the train for seven or eight hours and the small quantity of food we had been given was to last us till the morning. A railway engine drew five cattle trucks into the station and 40 of us were entrained in each truck and the doors were bolted on the outside. We were in for a pretty grim time. There was scarcely any light for one thing and the small rectangular opening at each end did not admit nearly enough air for 40 men. So we thought it was only to be for seven or eight hours we ate up all our food and prepared to make the best of it. But that journey lasted exactly 49 1/2 hours and it exceeded in bodily discomfort anything I'd suffered up to this time. We got no more food from the Germans and in consequence became intensely hungry, but the chief trouble was lack of air. We were so crowded that it was necessary to remain in a vertical position in order to be able to breathe. A few minutes on the floor at a time was all one could take without being suffocated and getting up and down from the floor was itself a struggle as there were so many legs and feet to contend with. We were like a lot of distressed goldfish in a bowl of stale water- constantly poking our noses upwards to gulp in morsels of air. To one who is very tired, having to remain upright for many hours is, of itself, a prolonged and delicate torture.

At Munich there was a Red X buffet and they passed in some ersatz black coffee in paper containers - un-sweetened of course. There was not enough to go round but we all got at least a sip. I believe also some small pieces of sausage and bread came in but there was not enough of this to go round. At another station the Red X passed in tiny portions of soup in paper containers and there was enough of this for everyone to get a sip at least. I took a very good view of the Red X at this time and, though, at times since I have heartily cursed them for mismanagement for not doing things I knew they could so easily have done, I yet remain grateful and, in company with all other prisoners of war, I have to thank this organisation for a very good deal.

One little addition to our diet we got for ourselves. We were shunted into the goods siding of a little country station and the engine was taken off. As usual at such halts we cried loudly the German word "Abort" and this cry usually resulted in the sentries unlocking the doors and allowing us to come out on the ground for a few minutes. We got our rare drinks of water from railway taps in this way. At this particular station there was a German automatic machine which some ingenious person found would respond to French money. We withdrew the entire contents of the machine in this way and acquired some (very valuable to us) peppermint creams.

Of the tedium of this journey I will not say more, except that it stimulated late feelings of sympathy for horses and cattle who are conveyed in this way. We never travelled fast: we just bumped along. Frequently we travelled over the same ground twice. We passed through Munich twice for instance, having in the interval been right down to the extreme south of Germany and back again. It was said that there were two places called Lanfon, which was the name of our destination, and the railway company has sent us to the wrong one. I don't know whether this was true. So we never had any real information in those days and there was always an ingenious explanation for everything.

Eventually, however, we did arrive at the correct Lanfon . This was a pleasantly situated little town in Bavaria, about 18 kms from Salzburg, which could be plainly seen on clear days. Behind Salzburg rose majestic and impressive, the beautiful snowclad peaks of the Austrian Alps.

At Lanfon Railway Station we were met by the notorious Dr Frey - also majestic and beautiful, though in a different way. Dr Frey was a large elderly German with a thick neck, a skin like a wrinkled parchment and an eyeglass. An iron cross on a ribbon hung round his neck and his uniform was just a little bit brighter in colour, just a little bit finer in texture and just a little bit longer in cut than that of the other Germans. He was a gorgeous figure and was immediately renamed "The Purple Emperor". A short march from the station and we passed through the barbed wire gates of Oflag Vll C. Our travelling was over for some time to come. And so was our contact with the outside world.

I am far from complaining about the hardships of this journey. Prisoners of war are entitled to expect hardships and I consider that in reaching my permanent camp after a journey which lasted only 10 days and which in no way permanently injured the health of anyone, I have been very lucky. I was certainly much more fortunate than many others have been. The 51st division, for instance, had to march long distances across Holland and Belgium and, in the 1914 war, Gen Townshend's force which was captured by the Turks at Kut had to march under appalling conditions. A high percentage failed to do it.

*****Note made in May 1945.

At the time this was written the long marches that commenced in the winter of 1945 from prison camps in eastern Germany and Poland had not been contemplated. On these marches the casualties were severe. Frostbite was the chief trouble. An American Colonel told me that his camp of 1600 American officers was evacuated on foot on the approach of the Russians. There had been a number of deaths and he knew of many amputations of limbs necessitated by frostbite. Out of the original 1600, only 600 odd completed the march which covered some hundreds of miles. He had no information about those who fell out. This may not however be as bad as it seems, for paradoxically, the German doctors have always given of their best to British and American nationals who needed treatment (I am not sure how they treated Russians). Almost always one could be sure of a square deal from the German medical services.

In England, it is true, our prisoners are treated rather differently, or they were when I was last there. Officer prisoners were conveyed 1st class on the railways and they were permitted to avail themselves of the full facilities of the restaurant car. A German flying officer who had managed to escape told us he had been "staggered" at the amount of food he had been given. He had nothing but praise regarding his treatment. This officer had been sent by Goering to visit our camp and make a comparative report on conditions. In spite even of this, I do not complain. I expect things to be different. For one thing the Germans have much less to offer and I draw consolation from the thought that the ever increasing shortage of essential things in the country is bound to have its influence on the end of the war. And, in the second place, I do not expect to find that German methods resemble ours. If there were not indeed such differences why should we be fighting?

And there is yet another respect in which the party I was captured with must consider itself fortunate. They were all safely evacuated from the forward areas without any fatal incidents having taken place. That such incidents should occasionally take place was I suppose inevitable but I know of them by hearsay only. In those forward areas killing, and being killed, excited little more emotion than cutting down a plant in the garden, certainly far less than the human destruction of a favourite dog. Tempers were not always calm at this time and irresponsible individuals there always are - on both sides. Some British officers and men could not at once adjust themselves to their new conditions and some German officers and men were in no mood to waste any time over difficult prisoners and so inevitably more British lives were lost. I make no real complaint about this, though it was certainly unfortunate and unecessary, for I can see both sides. But I do rather complain that some men should have been shot for things so trivial as merely being in possession of a little humorous card on which was printed a slightly pornographic effigy of Hitler. These cards had been circulating amongst our troops at that time! I think they were printed in France.

I do not propose to give any detailed record of events in our prison camps. It could not be interesting for, at its best, it would be registered by the necessary omission, for security reasons, of any reference to the one subject that might have made it so. It is a prisoner's duty to try to escape and that is the only duty left he is able to perform.

We had been in captivity for almost a year before anything like the full story of Dunkirk began to filter through. This news was brought to us by newly arrived prisoners. We then heard of the great welcome accorded by the people of England to those who got home and this news slightly depressed us. It was not entirely that we envied these people their good fortune, though not unnaturally we did feel something of this. It was rather, I think, that we felt that if there was any honour in getting large British forces back to British soil such honour belonged least of all to those who were themselves got back. Such honour as there was, belonged rather to those who got them away in boats at Dunkirk and by those whose gallant and costly rear guards extending as far back as 40 miles behind Dunkirk enabled the evacuation to take place at all.

The 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment, some of whose work I have endeavoured to describe, were amongst those who performed this very important task. If the effort made by a unit is proportional to the casualties sustained, and I think it must be considered so, then the effort made by this particular unit must be notable amongst the achievements in France in 1940, for I know of no unit that had a longer list of casualties in that campaign. I am aware that in the version of Lord Gort's report that was received here, much greater prominence was given to the importance of the resistance put up by the units that were at Calais. In fact no reference whatever was made to those units that necessarily had to be sacrificed behind Dunkirk. There may or may not have been political reasons for this misplacement of emphasis, as I personally think it to be, but whatever the reason, the fact remained that the German commentators, one of which I have quoted, did not fail to recognise the importance of the resistance at other places. But aside from the importance of a regiment's achievement which may always be a matter of opinion, and never perhaps wholly unbiased, the cold figures of dead and wounded are the sole means of measuring the extent of the efforts made. The numbers of killed and wounded amongst those units that operated at Calais were not high in comparison to the devastation suffered elsewhere. But it must not be thought that I wish in the slightest degree to detract from the value to the whole campaign of the achievement at Calais. That is very far removed from my intention. What I am endeavouring to do is to distinguish two factors (a) efforts put forth and (b) the value of the results achieved. I maintain that it is a grave error to suppose that these two elements are necessarily closely related.

And now, I feel it is time to bring this narrative to a close. It may well be that in the opinion of some I have carried it on too far already. Indeed, had I intended it to serve as a regimental history, then clearly I have passed the point at which an ending was logically possible; the point at which officers and other ranks prisoners of war became separated from each other. But it was with a definite purpose in my mind that I have insisted in taking my reader beyond this point. I felt that by doing so he would be less likely to disregard the warning I tried to emphasise in the preface to this narrative, viz: that it must on no account be regarded as a regimental history in spite of the fact that parts of it would undoubtedly bear a semblance to such. I repeat it is not a regimental history. It is purely a personal record. To regard it in any other light would be grossly unfair because much that is worthy of inclusion in the records of the regiment of which I write is necessarily lacking. Names that ought to be mentioned are unrecorded. It is, however, unfortunate that the documents necessary to support a regimental history do not exist. Every line of all narratives must necessarily be based on memory and further there is no single person now alive who was in a sufficiently central position the whole time to enable him to attempt to write a complete story without having to include a good deal of hearsay and guesswork. Whether such a work can be successfully undertaken in the future is open to question. It is certain it cannot be done until information has been gathered from all the survivors and items selected on which there is a fair measure of agreement and different points of view taken into account.

The nature of my own contribution to such a work, should it ever be wanted seemed clearly prescribed. It was to confine myself to what I knew about personally and to avoid all speculation. This is what, in this narrative, I have tried to do. I have, however, felt in rather a special position to write about the Royal Norfolk Regiment. In my capacity of an officer who does not wear their badge I have been certainly more at liberty to make comments which, if they had been made by an officer for his own unit, might have seemed extravagant and lacking in proper modesty, thus inviting the reader to take the whole of the story with the proverbial grain of salt. Officially then, I explain that my attachment to the unit of which I write came to an end with the beginning of my captivity for so I suppose never having been told so. But my love for them is more enduring than the posting of a name in the Army Record office and, I can truly say, without feeling disloyal to my own regiment with whom it has not been my privilege to do any active service, that I wish I were really entitled to wear as my own the badge of the unit I had the great honour to try and serve for my short time in France in 1940.

Examples of the original narratives are shown above.

Hastings Narrative Part Two

Preface

I now proposed to take this narrative a little further. From this point onwards I'm able to write with rather more sureness because I am able to draw on notes made soon after the events happened, when the recollection of them was still fresh in my mind. So I have explained in the preface, there have been important security reasons for not putting on paper, prematurely, too much about actual operational happenings; but there were, of course, fewer reasons why events that happened after capture should not be fairly fully recorded; and I did in fact avail myself of such an opportunity. Nevertheless I could not entirely ignore the possibility of censorship. I had to write always with a view to the possibility of what I wrote falling into German hands as did in fact happen on two occasions. Had I written with complete frankness and, had I not toned down very considerably what I wrote, the following notes would certainly have been destroyed and I should have got a week or two in the "cooler" which was solitary confinement with a diet of bran and water, one blanket and no palliasse in those days.

Now I return to the 27 May 1940- the day on which Battalion Headquarters of the 2nd Battalion Royal Norfolk regiments finally surrendered.

In the early part of the day it will be seen that we had been able to inflict far more damage on the enemy than they had been able to inflict on us, but the situation had gradually deteriorated. From the time I destroyed the Battalion papers onwards, our power to inflict any more damage on the enemy was out of all proportion to the damage we had to take.

We were not well informed about what was going on around us, but this was comparatively unimportant against orders to stand to the "last man and the last round". Virtually we did this, although it is true there were probably a few unexpended rounds in the magazines of some of the rifles and I had six rounds in my pistol which I did not fire; but there was nothing whatever for the Bren guns. Situated as we were, with everything shelled out and now in flames, our only cover, a road side ditch pointing the wrong way, our last chance of doing anything more to the enemy was gone. I was the senior officer of the party and I accepted the responsibility for surrendering. Nobody liked it. I myself was unwounded. If the reader wishes to think of something unutterably humiliating he may try to imagine my feelings. I will not describe them to him.

I walked down the road with the towel held high above my head but my eyes were naturally upon the ground. The muzzle of a Tommy gun was poked at me. The bloody thing could go off for all I cared. I did not look at the face of the soldier who held it, nor at the one took away my revolver. I did not see who snatched the field glasses from the strap around my neck, nor did I care who was the owner of the pair of hands that went through my haversack. If there was a horrible grin of triumph on the faces of these men I did not see it. We went on like a funeral procession.