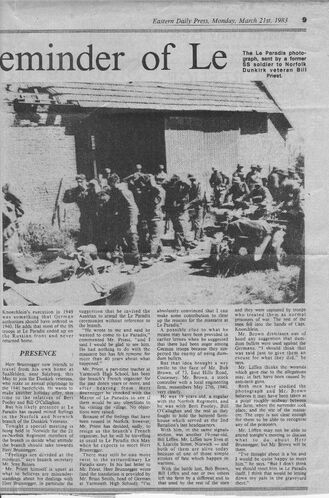

Herbert Brunnegger

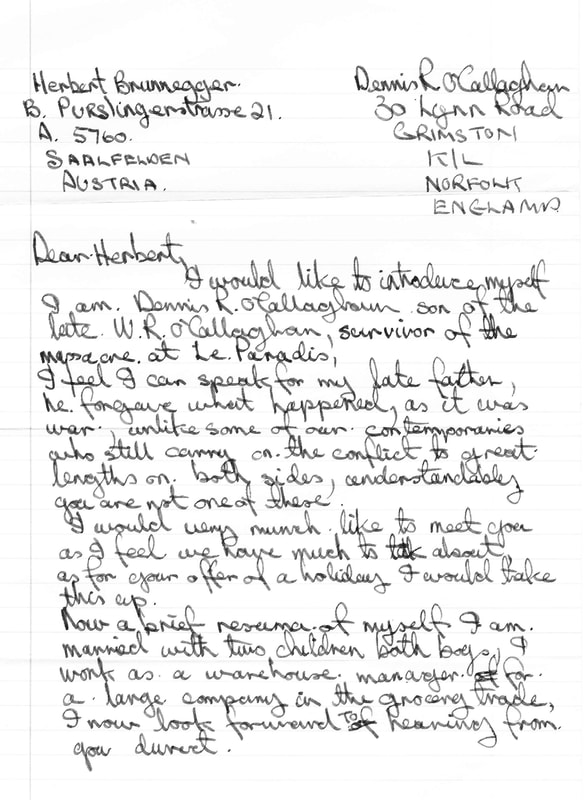

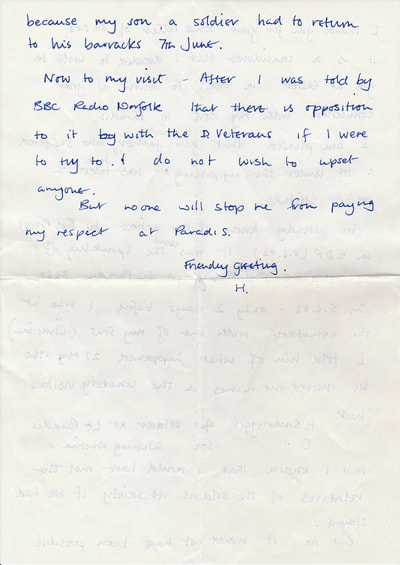

In 1983 Dennis O'Callaghan sent a letter to hotelier Herbert Brunnegger in Austria.

But this was no ordinary correspondence. Herr Brunnegger was the man who photographed the lead-up to the massacre at Le Paradis.

Dennis' letter of conciliation said much about the humanity and views of the O'Callaghan family and the fact that Bill O'Callaghan bore no hard feelings towards Brunnegger, who had been a German soldier.

Later that year, Dennis received a reply at his home near King's Lynn, Norfolk, from Herr Brunnegger.

Below we publish Dennis' letter to Herbert Brunnegger (pictured above in his German uniform) and Brunnegger's reply.

But this was no ordinary correspondence. Herr Brunnegger was the man who photographed the lead-up to the massacre at Le Paradis.

Dennis' letter of conciliation said much about the humanity and views of the O'Callaghan family and the fact that Bill O'Callaghan bore no hard feelings towards Brunnegger, who had been a German soldier.

Later that year, Dennis received a reply at his home near King's Lynn, Norfolk, from Herr Brunnegger.

Below we publish Dennis' letter to Herbert Brunnegger (pictured above in his German uniform) and Brunnegger's reply.

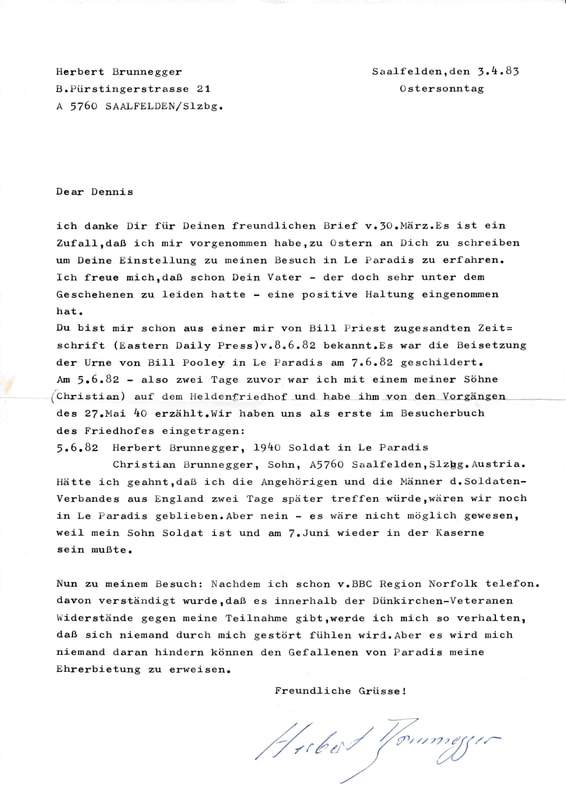

Below is an English transcription of the letter from Herbert Brunnegger. Click on the pages to increase their size.

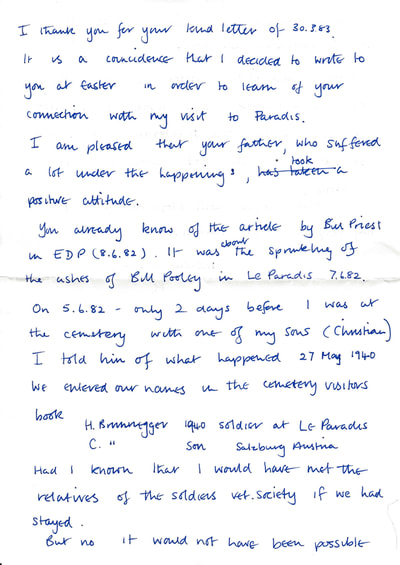

"I thank you for your kind letter of. It is a co-incidence that I decided to write to you at Easter in order to learn of your connection with my visit to Paradis.

I am pleased that your father, who suffered a lot under the happenings, took a positive attitude.

You already know of the article by Bill Priest in the EDP (8.6.82) - only two days before I was at the cemetery with one of my sons (Christian). I told him of what happened 27 May, 1940. We entered our names in the cemetery visitors' book:

H. Brunneger 1940 soldier at Le Paradis

C. Brunneger son Salzburg, Austria

Had I known that I would have met the relatives of the soldiers vet society if we had stayed.

But no it would not have been possible because my son, a soldier, had to return to his barracks 7th June.

Now to my visit. After I was told by Radio Norfolk that there is opposition to it with the D Veterans if I were to try to. I do not want to upset anyone.

But no-one will stop me from paying my respect at Paradis.

Friendly greeting

H

I am pleased that your father, who suffered a lot under the happenings, took a positive attitude.

You already know of the article by Bill Priest in the EDP (8.6.82) - only two days before I was at the cemetery with one of my sons (Christian). I told him of what happened 27 May, 1940. We entered our names in the cemetery visitors' book:

H. Brunneger 1940 soldier at Le Paradis

C. Brunneger son Salzburg, Austria

Had I known that I would have met the relatives of the soldiers vet society if we had stayed.

But no it would not have been possible because my son, a soldier, had to return to his barracks 7th June.

Now to my visit. After I was told by Radio Norfolk that there is opposition to it with the D Veterans if I were to try to. I do not want to upset anyone.

But no-one will stop me from paying my respect at Paradis.

Friendly greeting

H

Herbert Brunnegger was a 17-year-old SS soldier who in May 1940 took a photograph of the doomed prisoners of the Royal Norfolks and other regiments being marched to their death outside the barn at Creton's Farm in Le Paradis.

Herr Brunnegger later learned just what had happened to the soldiers after he took the photograph and was haunted by what he found out.

After the war he took it upon himself to find the two survivors - Privates Bill O'Callaghan and Bert Pooley. He contacted the Commonwealth War Graves Commission with the idea of enlisting their help to trace the two men to offer them a holiday at his hotel in Saalfelden near Salzburg.

Sadly by this time both Bill and Bert had died.

Herbert Brunnegger was the youngest professional soldier in the pre-war German army, having joined the Waffen SS in April, 1938 at the age of 15. After service in Poland he found himself in Northern France. He was separated from his unit while crossing La Bassee Canal near Le Paradis and he came across the Norfolks by chance.

Herr Brunnegger later said that he was sent away from the scene before the shootings took place but claims to have seen Fritz Knoechlein later that day shooting at women civilians. He said he felt revulsion when he learnt about what had happened.

He admitted to seeing the column of prisoners by the barn with many of them reaching out in despair to him, showing pictures of their families. Herr Brenegger then admits that he saw two machine guns set up in front of the prisoners. On inquiring what the machine guns were to be used for he was told "to shoot the prisoners."

He expressed a wish to return to Le Paradis after the war to attend one of the village's annual commemoration services - something that didn't sit easily with some members of either the Norfolk Regiment or the Dunkirk Veterans' Association. He hadn't had any direct connection with the massacre but felt considerable remorse.

Herbert Brunnegger died in 2002. He wrote a number of books including: "Saat in den Sturm: Ein Soldat der Waffen SS Berichtet" - "Seed in the Storm: A Soldier of the Waffen SS."

Herr Brunnegger later learned just what had happened to the soldiers after he took the photograph and was haunted by what he found out.

After the war he took it upon himself to find the two survivors - Privates Bill O'Callaghan and Bert Pooley. He contacted the Commonwealth War Graves Commission with the idea of enlisting their help to trace the two men to offer them a holiday at his hotel in Saalfelden near Salzburg.

Sadly by this time both Bill and Bert had died.

Herbert Brunnegger was the youngest professional soldier in the pre-war German army, having joined the Waffen SS in April, 1938 at the age of 15. After service in Poland he found himself in Northern France. He was separated from his unit while crossing La Bassee Canal near Le Paradis and he came across the Norfolks by chance.

Herr Brunnegger later said that he was sent away from the scene before the shootings took place but claims to have seen Fritz Knoechlein later that day shooting at women civilians. He said he felt revulsion when he learnt about what had happened.

He admitted to seeing the column of prisoners by the barn with many of them reaching out in despair to him, showing pictures of their families. Herr Brenegger then admits that he saw two machine guns set up in front of the prisoners. On inquiring what the machine guns were to be used for he was told "to shoot the prisoners."

He expressed a wish to return to Le Paradis after the war to attend one of the village's annual commemoration services - something that didn't sit easily with some members of either the Norfolk Regiment or the Dunkirk Veterans' Association. He hadn't had any direct connection with the massacre but felt considerable remorse.

Herbert Brunnegger died in 2002. He wrote a number of books including: "Saat in den Sturm: Ein Soldat der Waffen SS Berichtet" - "Seed in the Storm: A Soldier of the Waffen SS."

After the war Herbert Brunnegger was featured in a major article in the Eastern Daily Press newspaper. In this article he stated that he was haunted by his discovery of what happened after he took the infamous photograph (included above).

Brunnegger decided to try and track down the survivors as we have described above. The article states that he was separated form his unit whilst crossing the La Bassee Canal and seems to have come across the captured Norfolks by chance. He says he was sent away from the scene before the shootings occurred.

He believed Knoechlein would be court marshalled for his actions in ordering the massacre. He felt the German authorities should have ordered the execution of Knoechlein during the war.

In the article he also states that from the wounds he witnessed on his fallen colleagues it appeared that Dum Dum bullets were being used.

The most relevant piece of evidence in respect of the use of Dum Dum bullets came at the trial of Fritz Knoechein given by SS Sergeant August Leitl who had commanded No 3 Platoon in Knoechein’s Company. The following is quoted from The Vengeance of Private Pooley by Cyril Jolly and is written with the permission of the Jolly family.

‘Regarding the use of dum-dum ammunition he (August Leitl) said he was responsible for collecting the Company’s dead and he saw each wound. He was also sergeant-artificer and an ammunition expert. He denied the wounds were caused by dum-dum. Almost every dead man had been shot in the head and the wounds were large, but he maintained these were caused by the bullets striking the steel helmets and flattening themselves. “We were very exposed” he said.

"If somebody just lifted his head he was killed. The British used snipers very skilfully.” He said the Germans buried their dead immediately in front of the house where the British surrendered’.

There has never been any evidence to suggest that dum dum bullets were used as Brunnegger claims.

Definition of Dum-Dum bullet: A Dum-Dum bullet is an expanding bullet designed to expand on impact, sometimes as much as twice the diameter. It is known colloquially as Dum-Dum the name being taken from the Dumdum Arsenal, near Calcutta, India. It was often used for big game hunting.

The newspaper article article states that Brunnegger felt remorse for more than 40 years for what happened at Le Paradis.

However, 0ver 30 years after the end of the war, Brunnegger wrote a book entitled Saat in den Sturm: Ein Soldat der Waffen-SS berichtet which is translated as "Seed in the Storm : A soldier of the Waffen SS." This book seems to contradict much of what he had previously said on the massacre and puts a rather different slant on his involvement in the area of Le Paradis on that fateful day. The following translations are courtesy of the Royal Scots Regimental Museum and are taken from "Saat in den Sturm." We start with Brunneggers comments about the build up:

"Gradually we pushed the British towards Béthune over the La Bassée Canal which we reached on 25th May 1940. We dig in to the north west of Béthune between the road and the canal, directly in front of an agricultural building.

"The Tommys are in the hinterland on the other side of the canal. They confine themselves to firing their artillery which is designed to keep us on our toes. Otherwise they do not trouble us. All we see is a Fieseler Storch (editor note a small German reconnaissance aircraft) from our own Luftwaffe – it circles overhead several times during the day. Oddly enough, every time it does this the artillery fire becomes more accurate. Our enquiries result in us finding out that no German reconnaissance plane of this type is scheduled for our sector. When it makes an appearance for the fifth time our own anti-aircraft guns shoot it from the sky. It had been flown by English pilots under German markings."

Under the Heading "The Shame of Le Paradis" Brunnegger has the following to say.

"On the evening of 26th May we are briefed on the situation. Opposite us are the Royal Norfolk Regiment and the Royal Scots Regiment of the British Expeditionary Force.

"Our 2nd and 3rd Companies are ready to advance over the canal. My telephone section is assigned to no 1 Company so I am back with my former Company Commander. Connections with Battalion HQ are established by using a light field cable.

"It is still light when nos 2 and 3 Companies start to cross the canal. It is pouring with rain and the artillery fire to the right of us is getting ever more intense. The Companies have to cross the canal on two bridges which the Pioneers have had to repair and make good. Immediately they gain ground.

"While the Pioneers reinforce the bridges over the canal we are brought across under cover of darkness to an area already cleared. There we secure our positions by quickly digging in.

"In the early hours of 27th May my telephone section receives orders to switch immediately to 3 Company HQ after which the entire section is to go into action. The HQ of Company Commander SS Captain Knöchlein is set up in some old World War 1 positions in a wood. Once again we set up a connection to Battalion HQ. Afterwards we repair the line in several places whilst under fire from the English artillery.

"The attack is renewed. A week sun is rising out of ground mist. A sign post points to Le Cornet Malo. Mortars and machine guns move into position on the edge of the wood and fire at recognisable enemy targets in a village a couple of hundred metres in front of us. While they do this our soldiers move forward on both sides of the path. I come across a young Englishman. His face is distinctive and brown but the proximity of death is making his skin go pale. He is standing up leaning against a wall made of earth. In his eyes there is an indescribably hopeless expression while the whole time bright spurts of blood are coming out of a wound at the base of his neck. In vain his hands try to press on a vein in order to try and keep the life in his body. He cannot be saved.

"Onwards! A surprise as a burst of machine gun fire hit a section as it moves out of a cutting. The bursts toss them into a tangle of bodies. One stands up and sways past me to the rear – he has a finger stuck into a hole in his stomach.

"Snipers shoot from the roofs of the village we are attacking and pin us down. They cause considerable losses. When we try to attend to the wounded we establish that a number of them have exit wounds from the bullets which are the size of a hand and that in most cases they cannot be saved. They bleed to death in our hands. We suspect from the small entry hole of the bullets that the English are using Dum Dum bullets. This is forbidden under international law,

"Sniper fire again pins us to the ground. We each either get behind cover or lie flat in the grass. The machine guns fall silent. The soldiers from no 1 Company have made an attack and lie with dreadful wounds behind their weapons. Only the operators of two mortars in their World War 1 craters remain unscathed. They intensify their fire on to anything which could shelter the snipers. This at least gives us an opportunity to rescue our wounded. When the mortars have used up all their ammunition the battlefield belongs once more to the English.

"The wounded describe how their section stormed an enemy position during the action. The English soldiers surrendered after a close quarter fight and ask for help for two wounded men who were lying under blankets. When the section moved on the English soldiers who had allegedly been wounded threw hand grenades at the soldiers who had spared them.

"Both the wounds which had been caused by the mysterious ammunition and the report of the wounded soldiers serves to dampen our spirits and make our opponents appear in new light. After another similar episode of unfair treatment in the same wood we have to accept that this deceitful method of fighting is normal for our opponents.

"Only after many hours and only after the defenders of Le Cornet Malo are fired upon from their other flanks does our Company succeed in entering this small village. Those still alive among the British have retreated towards Le Paradis. In an instant the enemy are no longer around. Ammunition for the infantry and mortars is brought forward. The wounded wait for transport to take them away and the depleted sections are reorganised. Some eat from their haversacks without any thought of the consequences of having been shot in the stomach.

"We bury our dead in a meadow near the road which we take to our next battle. It leads to a somewhat larger settlement. The general direction of attack is towards the north-east.

Before long the machine gun nests of the invisible defenders suddenly open up on us. The enemy soldiers are able to make best use of the terrain which is made up of ditches, wind breaks, straw bale dumps, isolated farmsteads, tall grass and newly grown wheat. Snipers and machine gun nests are hidden in the extensive area over which we plan to attack. Our supporting mortars cannot be used to their full effect. The countryside in front of Le Paradis is wide and flat.

"The English defend themselves with incredible bravery and doggedness. Again the losses in terms of wounded and dead pile up. Again we are completely pinned to the ground in front of the enemy who is totally invisible and whose ability commands our admiration. We have to adapt ourselves completely to the enemy’s tactics. We work ourselves forward by creeping, crawling and slithering along. The enemy retreats skilfully and without showing himself. However it is a thousand metres to the place which we have been ordered to attack. After the meadow which does afford us protection there are broad deep level fields. Any idea of crossing this without support would be totally suicidal. I am reminded of doing this on exercise – then the artillery supported us wonderfully! I conjure that manoeuvre in my mind today in recipe book terms. “You need so and so……” But I have not seen anything of our big Skoda guns. Where are they dug in out of sight?

"The HQ of our Battalion Commander, Lt Col Fortenbacher, a veteran of World War 1 , is moved further forward. I have to take up the old telephone line as far as it has been overtaken and install a new connection. Cursing I crawl all the way back, winding up the 500 metre long cable on its small spool as I go. How I hate this aspect of war! As soon as I am out of range of the Tommies I set off to search for the HQ of the Commanding Officer. There, there are problems with telephones, I have to connect the new line and then go off again to Knöchlein’s no 3 Company. In the meantime our opponents have retreated to Le Paradis and cleared the area in front of us. We have moved nearer. Mortars and machine guns now have concrete targets to aim at once more. In spite of this the resistance of our opponents is so effective that we cannot make it to the village without heavy losses.

"Once again we are stuck. There are further heavy losses after each attempt to get the attack on Le Paradis under way. From number 1 Battalion HQ we can see the area in front of number 3 Company. We must acknowledge that things cannot go on like this.

"Where is the Division’s armour and where is tour (our?) artillery? When the field telephone rings I pass it to the Company Commander. Behind us a howitzer has been brought into position in order to break the resistance of Le Paradis’s defenders. After a short time the first shell whooshes right over our heads and crashes down in their presumed positions. Now it must be enough and white flags must soon appear. Rubble, fire and thick smoke show where the shells have landed. Onwards over the last hundred metres!

"But then the machine guns open up from a large building which is several storeys high. At the same time the infantry set up- a withering fire which sends our Kamerads to the ground. We try to use every small elevation and small dip in the field. No-one digs in in order to avoid the attention of the snipers. Dammit, they must see our predicament. Is the howitzer no longer to be used? But soon the shells resume their attack on the main buildings of the village. It is where the defenders’ return fire is the fiercest.

"From my position I can see that motorcycle dispatch riders are getting into the village from the far side during the artillery bombardment. Once there they are taking up the fight.

Captain Knöchlein gives the signal to attack. The artillery gives us effective cover and we make it to the village without any further losses. In the village the motorcyclists are already fighting to good effect.

"White flags appear hesitantly .We watch them carefully and suspiciously as they emerge into captivity. Most of the British are wounded. The costly fight for the Le Bassée Canal and for Le Paradis is at an end.

"I come across an old Kamerad whom I have known since we joined up. He tells me that a group of English soldiers in a stable block waved a white flag in order to surrender. We ceased fire. When the Germans came out of cover and drew near a machine gun shot them from the other side of the stable. The covering machine guns on our side fired at the British who leapt back into the stable block. They left 10 dead behind them,

"Part of the English forces have succeeded in getting away to the north. The surviving defenders of Le Paradis emerge from their positions in barns, lofts and cellars.

"Once we think we have cleared the village of enemy troops we are surprised by shots landing on the outskirts of the village. A well camouflaged English machine gun which we at first presumed was deserted has been manned by soldiers again. They have opened fire once more. Two of my Kamerads from the Machine Gun Company are the last sacrifices of the engagement.

"While our soldiers assemble together our dead are buried in shallow graves. There where they fell they find their peace. Thus three soldiers lie in a grave not far from the English machine gun which shot them down. Six men lie together in the midst of newly planted crops by a lonely gun by the canal. Many lie between the houses on the edge of the village. Wood is ripped from the fences in order to make crosses with names carved roughly in order to show who is at rest in the ground here. There is no song about good Kamerads, no salute and nothing said about heroism. We are thinking “Today it is thee, tomorrow it is we!” (The fight for the La Bassée Canal has cost our youthful Division 157 dead and over 500 wounded).

"Our army trucks are got ready. Ammunition and supplies are brought up and the wounded are brought to the main first aid post. Units which have come under fire are re-organised and re-equipped.

"I have just taken up the old telephone line from the fields to the rear when I see a large group of English prisoners by a farmhouse. Those that are not wounded are standing, the wounded are sitting and lying down in front on the ground. Many of them reach out in despair towards me with pictures of their families. Perhaps they think we are going to send them on leave?

"As I look more closely I notice two heavy machine guns which have been installed in front of them. Whilst I look on, surprised that two valuable machine guns should be used to guard the prisoners, a dreadful thought occurs to me. I turn to the nearest machine gun post and ask what is going on here. “They are to be shot!” is the embarrassed answer. I cannot grasp this and think there is some stupid joke behind these words. Therefore I ask again, “Who has ordered this?”

“Captain Knöchlein.” Now I know this is bitterly serious. I quickly hurry to catch up with my own section so I do not have (editor adds the word ‘to’) witness the shooting of the prisoners who are waiting for death with pictures of their families in their hands

"First there was the action with the terrible ammunition which was completely unknown to us. In addition there was the behaviour of the English towards our men who had intended to spare them. And now the imminent massacre of all prisoners as a result of a judgement delivered in haste! Were all of them guilty?. I saw no prisoners who were to be spared. Was it even Dum Dum ammunition or some other type of ammunition which has yet to be outlawed? When the English machine gun open fired unexpectedly while the remaining defenders wanted to surrender – could it not have been a case of poor co-ordination or nervousness? Were the ten British dead and slightly fewer casualties on our side the result of poor communications? Do I try to sooth things?

"Days later while we are fighting our way northwards Major Riederer from the General Staff is finding the bodies of 89 English soldiers. They are lying next to each other and are unarmed. They have been shot to death. His findings are reported immediately to the XVI Army Corps. At this stage I am still unaware of how often the most horrible crimes would be justified by the enemy as “Events of War” (Translation note-presumably a reference to a later action on the Eastern Front).

Brunnegger decided to try and track down the survivors as we have described above. The article states that he was separated form his unit whilst crossing the La Bassee Canal and seems to have come across the captured Norfolks by chance. He says he was sent away from the scene before the shootings occurred.

He believed Knoechlein would be court marshalled for his actions in ordering the massacre. He felt the German authorities should have ordered the execution of Knoechlein during the war.

In the article he also states that from the wounds he witnessed on his fallen colleagues it appeared that Dum Dum bullets were being used.

The most relevant piece of evidence in respect of the use of Dum Dum bullets came at the trial of Fritz Knoechein given by SS Sergeant August Leitl who had commanded No 3 Platoon in Knoechein’s Company. The following is quoted from The Vengeance of Private Pooley by Cyril Jolly and is written with the permission of the Jolly family.

‘Regarding the use of dum-dum ammunition he (August Leitl) said he was responsible for collecting the Company’s dead and he saw each wound. He was also sergeant-artificer and an ammunition expert. He denied the wounds were caused by dum-dum. Almost every dead man had been shot in the head and the wounds were large, but he maintained these were caused by the bullets striking the steel helmets and flattening themselves. “We were very exposed” he said.

"If somebody just lifted his head he was killed. The British used snipers very skilfully.” He said the Germans buried their dead immediately in front of the house where the British surrendered’.

There has never been any evidence to suggest that dum dum bullets were used as Brunnegger claims.

Definition of Dum-Dum bullet: A Dum-Dum bullet is an expanding bullet designed to expand on impact, sometimes as much as twice the diameter. It is known colloquially as Dum-Dum the name being taken from the Dumdum Arsenal, near Calcutta, India. It was often used for big game hunting.

The newspaper article article states that Brunnegger felt remorse for more than 40 years for what happened at Le Paradis.

However, 0ver 30 years after the end of the war, Brunnegger wrote a book entitled Saat in den Sturm: Ein Soldat der Waffen-SS berichtet which is translated as "Seed in the Storm : A soldier of the Waffen SS." This book seems to contradict much of what he had previously said on the massacre and puts a rather different slant on his involvement in the area of Le Paradis on that fateful day. The following translations are courtesy of the Royal Scots Regimental Museum and are taken from "Saat in den Sturm." We start with Brunneggers comments about the build up:

"Gradually we pushed the British towards Béthune over the La Bassée Canal which we reached on 25th May 1940. We dig in to the north west of Béthune between the road and the canal, directly in front of an agricultural building.

"The Tommys are in the hinterland on the other side of the canal. They confine themselves to firing their artillery which is designed to keep us on our toes. Otherwise they do not trouble us. All we see is a Fieseler Storch (editor note a small German reconnaissance aircraft) from our own Luftwaffe – it circles overhead several times during the day. Oddly enough, every time it does this the artillery fire becomes more accurate. Our enquiries result in us finding out that no German reconnaissance plane of this type is scheduled for our sector. When it makes an appearance for the fifth time our own anti-aircraft guns shoot it from the sky. It had been flown by English pilots under German markings."

Under the Heading "The Shame of Le Paradis" Brunnegger has the following to say.

"On the evening of 26th May we are briefed on the situation. Opposite us are the Royal Norfolk Regiment and the Royal Scots Regiment of the British Expeditionary Force.

"Our 2nd and 3rd Companies are ready to advance over the canal. My telephone section is assigned to no 1 Company so I am back with my former Company Commander. Connections with Battalion HQ are established by using a light field cable.

"It is still light when nos 2 and 3 Companies start to cross the canal. It is pouring with rain and the artillery fire to the right of us is getting ever more intense. The Companies have to cross the canal on two bridges which the Pioneers have had to repair and make good. Immediately they gain ground.

"While the Pioneers reinforce the bridges over the canal we are brought across under cover of darkness to an area already cleared. There we secure our positions by quickly digging in.

"In the early hours of 27th May my telephone section receives orders to switch immediately to 3 Company HQ after which the entire section is to go into action. The HQ of Company Commander SS Captain Knöchlein is set up in some old World War 1 positions in a wood. Once again we set up a connection to Battalion HQ. Afterwards we repair the line in several places whilst under fire from the English artillery.

"The attack is renewed. A week sun is rising out of ground mist. A sign post points to Le Cornet Malo. Mortars and machine guns move into position on the edge of the wood and fire at recognisable enemy targets in a village a couple of hundred metres in front of us. While they do this our soldiers move forward on both sides of the path. I come across a young Englishman. His face is distinctive and brown but the proximity of death is making his skin go pale. He is standing up leaning against a wall made of earth. In his eyes there is an indescribably hopeless expression while the whole time bright spurts of blood are coming out of a wound at the base of his neck. In vain his hands try to press on a vein in order to try and keep the life in his body. He cannot be saved.

"Onwards! A surprise as a burst of machine gun fire hit a section as it moves out of a cutting. The bursts toss them into a tangle of bodies. One stands up and sways past me to the rear – he has a finger stuck into a hole in his stomach.

"Snipers shoot from the roofs of the village we are attacking and pin us down. They cause considerable losses. When we try to attend to the wounded we establish that a number of them have exit wounds from the bullets which are the size of a hand and that in most cases they cannot be saved. They bleed to death in our hands. We suspect from the small entry hole of the bullets that the English are using Dum Dum bullets. This is forbidden under international law,

"Sniper fire again pins us to the ground. We each either get behind cover or lie flat in the grass. The machine guns fall silent. The soldiers from no 1 Company have made an attack and lie with dreadful wounds behind their weapons. Only the operators of two mortars in their World War 1 craters remain unscathed. They intensify their fire on to anything which could shelter the snipers. This at least gives us an opportunity to rescue our wounded. When the mortars have used up all their ammunition the battlefield belongs once more to the English.

"The wounded describe how their section stormed an enemy position during the action. The English soldiers surrendered after a close quarter fight and ask for help for two wounded men who were lying under blankets. When the section moved on the English soldiers who had allegedly been wounded threw hand grenades at the soldiers who had spared them.

"Both the wounds which had been caused by the mysterious ammunition and the report of the wounded soldiers serves to dampen our spirits and make our opponents appear in new light. After another similar episode of unfair treatment in the same wood we have to accept that this deceitful method of fighting is normal for our opponents.

"Only after many hours and only after the defenders of Le Cornet Malo are fired upon from their other flanks does our Company succeed in entering this small village. Those still alive among the British have retreated towards Le Paradis. In an instant the enemy are no longer around. Ammunition for the infantry and mortars is brought forward. The wounded wait for transport to take them away and the depleted sections are reorganised. Some eat from their haversacks without any thought of the consequences of having been shot in the stomach.

"We bury our dead in a meadow near the road which we take to our next battle. It leads to a somewhat larger settlement. The general direction of attack is towards the north-east.

Before long the machine gun nests of the invisible defenders suddenly open up on us. The enemy soldiers are able to make best use of the terrain which is made up of ditches, wind breaks, straw bale dumps, isolated farmsteads, tall grass and newly grown wheat. Snipers and machine gun nests are hidden in the extensive area over which we plan to attack. Our supporting mortars cannot be used to their full effect. The countryside in front of Le Paradis is wide and flat.

"The English defend themselves with incredible bravery and doggedness. Again the losses in terms of wounded and dead pile up. Again we are completely pinned to the ground in front of the enemy who is totally invisible and whose ability commands our admiration. We have to adapt ourselves completely to the enemy’s tactics. We work ourselves forward by creeping, crawling and slithering along. The enemy retreats skilfully and without showing himself. However it is a thousand metres to the place which we have been ordered to attack. After the meadow which does afford us protection there are broad deep level fields. Any idea of crossing this without support would be totally suicidal. I am reminded of doing this on exercise – then the artillery supported us wonderfully! I conjure that manoeuvre in my mind today in recipe book terms. “You need so and so……” But I have not seen anything of our big Skoda guns. Where are they dug in out of sight?

"The HQ of our Battalion Commander, Lt Col Fortenbacher, a veteran of World War 1 , is moved further forward. I have to take up the old telephone line as far as it has been overtaken and install a new connection. Cursing I crawl all the way back, winding up the 500 metre long cable on its small spool as I go. How I hate this aspect of war! As soon as I am out of range of the Tommies I set off to search for the HQ of the Commanding Officer. There, there are problems with telephones, I have to connect the new line and then go off again to Knöchlein’s no 3 Company. In the meantime our opponents have retreated to Le Paradis and cleared the area in front of us. We have moved nearer. Mortars and machine guns now have concrete targets to aim at once more. In spite of this the resistance of our opponents is so effective that we cannot make it to the village without heavy losses.

"Once again we are stuck. There are further heavy losses after each attempt to get the attack on Le Paradis under way. From number 1 Battalion HQ we can see the area in front of number 3 Company. We must acknowledge that things cannot go on like this.

"Where is the Division’s armour and where is tour (our?) artillery? When the field telephone rings I pass it to the Company Commander. Behind us a howitzer has been brought into position in order to break the resistance of Le Paradis’s defenders. After a short time the first shell whooshes right over our heads and crashes down in their presumed positions. Now it must be enough and white flags must soon appear. Rubble, fire and thick smoke show where the shells have landed. Onwards over the last hundred metres!

"But then the machine guns open up from a large building which is several storeys high. At the same time the infantry set up- a withering fire which sends our Kamerads to the ground. We try to use every small elevation and small dip in the field. No-one digs in in order to avoid the attention of the snipers. Dammit, they must see our predicament. Is the howitzer no longer to be used? But soon the shells resume their attack on the main buildings of the village. It is where the defenders’ return fire is the fiercest.

"From my position I can see that motorcycle dispatch riders are getting into the village from the far side during the artillery bombardment. Once there they are taking up the fight.

Captain Knöchlein gives the signal to attack. The artillery gives us effective cover and we make it to the village without any further losses. In the village the motorcyclists are already fighting to good effect.

"White flags appear hesitantly .We watch them carefully and suspiciously as they emerge into captivity. Most of the British are wounded. The costly fight for the Le Bassée Canal and for Le Paradis is at an end.

"I come across an old Kamerad whom I have known since we joined up. He tells me that a group of English soldiers in a stable block waved a white flag in order to surrender. We ceased fire. When the Germans came out of cover and drew near a machine gun shot them from the other side of the stable. The covering machine guns on our side fired at the British who leapt back into the stable block. They left 10 dead behind them,

"Part of the English forces have succeeded in getting away to the north. The surviving defenders of Le Paradis emerge from their positions in barns, lofts and cellars.

"Once we think we have cleared the village of enemy troops we are surprised by shots landing on the outskirts of the village. A well camouflaged English machine gun which we at first presumed was deserted has been manned by soldiers again. They have opened fire once more. Two of my Kamerads from the Machine Gun Company are the last sacrifices of the engagement.

"While our soldiers assemble together our dead are buried in shallow graves. There where they fell they find their peace. Thus three soldiers lie in a grave not far from the English machine gun which shot them down. Six men lie together in the midst of newly planted crops by a lonely gun by the canal. Many lie between the houses on the edge of the village. Wood is ripped from the fences in order to make crosses with names carved roughly in order to show who is at rest in the ground here. There is no song about good Kamerads, no salute and nothing said about heroism. We are thinking “Today it is thee, tomorrow it is we!” (The fight for the La Bassée Canal has cost our youthful Division 157 dead and over 500 wounded).

"Our army trucks are got ready. Ammunition and supplies are brought up and the wounded are brought to the main first aid post. Units which have come under fire are re-organised and re-equipped.

"I have just taken up the old telephone line from the fields to the rear when I see a large group of English prisoners by a farmhouse. Those that are not wounded are standing, the wounded are sitting and lying down in front on the ground. Many of them reach out in despair towards me with pictures of their families. Perhaps they think we are going to send them on leave?

"As I look more closely I notice two heavy machine guns which have been installed in front of them. Whilst I look on, surprised that two valuable machine guns should be used to guard the prisoners, a dreadful thought occurs to me. I turn to the nearest machine gun post and ask what is going on here. “They are to be shot!” is the embarrassed answer. I cannot grasp this and think there is some stupid joke behind these words. Therefore I ask again, “Who has ordered this?”

“Captain Knöchlein.” Now I know this is bitterly serious. I quickly hurry to catch up with my own section so I do not have (editor adds the word ‘to’) witness the shooting of the prisoners who are waiting for death with pictures of their families in their hands

"First there was the action with the terrible ammunition which was completely unknown to us. In addition there was the behaviour of the English towards our men who had intended to spare them. And now the imminent massacre of all prisoners as a result of a judgement delivered in haste! Were all of them guilty?. I saw no prisoners who were to be spared. Was it even Dum Dum ammunition or some other type of ammunition which has yet to be outlawed? When the English machine gun open fired unexpectedly while the remaining defenders wanted to surrender – could it not have been a case of poor co-ordination or nervousness? Were the ten British dead and slightly fewer casualties on our side the result of poor communications? Do I try to sooth things?

"Days later while we are fighting our way northwards Major Riederer from the General Staff is finding the bodies of 89 English soldiers. They are lying next to each other and are unarmed. They have been shot to death. His findings are reported immediately to the XVI Army Corps. At this stage I am still unaware of how often the most horrible crimes would be justified by the enemy as “Events of War” (Translation note-presumably a reference to a later action on the Eastern Front).

Another Media Article featuring Brunnegger

SLAUGHTER AT THE BARN - (Eastern Evening News Wednesday March 27 1985) By James Ruddy

The massacre of Le Paradis still burns in the minds of many of Norwich and Norfolk’s war veterans.

Almost 100 Royal Norfolks were mown down after surrendering to the German SS on the withdrawal to Dunkirk in 1940.

Two badly wounded survivors helped to bring the officer behind the atrocity to the gallows.

Both are now dead. But they and the massacre victims will be remembered shortly when members of the Dunkirk Veterans Association leave Norwich for their annual Pilgrimage to the scene.

The black and white print will be presented to the local French mayor as a poignant reminder of a wartime episode recalled today by the EEN.

* * *

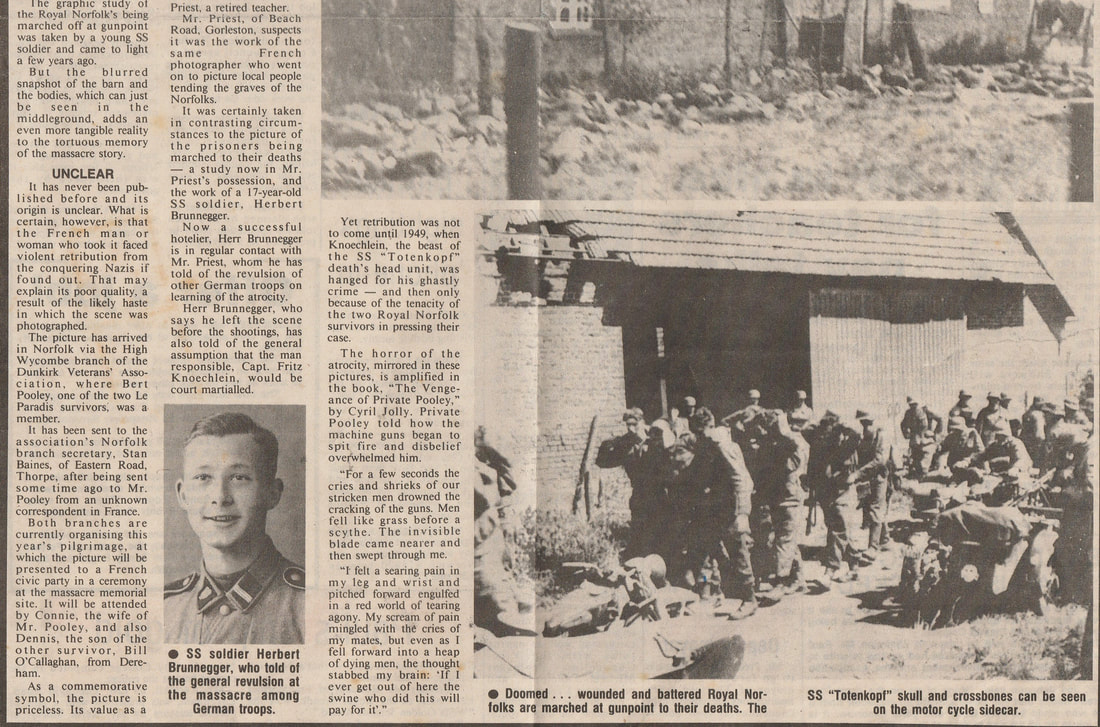

CAPTURED British soldiers, some clearly wounded, are marched at gunpoint by German SS troops past a damage barn on a sunny French day.

Shortly afterwards, their bodies lie under the same blistering sun, riddled by the bitter hail of machine gun fire.

The pictures on this page bear witness to the wartime atrocity which stole so many of Norfolk’s sons, Le Paradis.

The graphic study of the Royal Norfolks being marched off at gunpoint was taken by a young SS soldier and came to light a few years ago.

But the blurred snapshot of the barn and the bodies, which can just be seen in the middle ground, adds an even more tangible reality to the tortuous memory of the massacre story.

UNCLEAR

It has never been published before and its origin is unclear. What is certain, however, is that the French man or woman who took it faced violent retribution from the conquering Nazis if found out. That may explain the poor quality, a result of the likely haste in which the scene was photographed.

The picture has arrived in Norfolk via the High Wycombe branch of the Dunkirk Veterans’ Association, where Bert Pooley, one to the two Le Paradis survivors, was a member.

It has been sent to the association’s Norfolk branch secretary, Stan Baines, of Eastern Road Thorpe, after being sent some time ago to Mr. Pooley from an unknown correspondent in France.

Both branches are currently organising this year’s pilgrimage, at which the picture will be presented to a French civic party in a ceremony at the massacre memorial site. It will be attended by Connie, the wife of Mr. Pooley, and also Dennis, the son of the other survivor, Bill O’Callaghan, from Dereham.

As a commemorative symbol, the picture is priceless. It’s value as a record is underlined, however, by the courage of the photographer.

“The SS were in the village for a day or so afterwards so the picture would have been taken surreptitiously” said Dunkirk veteran Bill Priest, a retired teacher.

Mr. Priest of Beach Road, Gorleston suspects it was the work of the same French photographer who went on to take pictures of local people tending the graves of the Norfolks.

It was certainly taken in contrasting circumstances to the picture of the prisoners being marched to their deaths – a study now in Mr. Priest’s possession, and the work of a 17-year-old SS soldier, Herbert Brunnegger.

Now a successful hotelier, Herr Brunnegger is now in regular contact with Mr. Priest, whom he has told of the revulsion of other German troops on learning of the atrocity.

Herr Brunnegger, who says he left the scene before the shootings, has also told of the general assumption that the man responsible, Capt. Fritz Knoechlein, would be court martialled.

Yet retribution was not to come until 1949, when Knoechlein, the beast of the SS “Totenkopf” death’s head unit, was hanged for his ghastly crime – and then only because of the tenacity of the two Royal Norfolk survivors in pressing their case.

The horror of the atrocity, mirrored in these pictures, is amplified in the book, “The Vengeance of Private Pooley” by Cyril Jolly. Private Pooley told how the machine guns began to spit fire and disbelief overwhelmed him.

“For a few seconds the cries and shrieks of our stricken men drowned the cracking of the guns. Men fell like grass before a scythe. The invisible blade came nearer and then swept through me.

“I felt a searing pain in my leg and wrist and pitched forward engulfed in a red world of tearing agony. My scream of pain mingled with the cries of my mates, but even as I fell forward into a heap of dying men, the thought stabbed my brain. ‘If I ever get out of here the swine who did this will pay for it’”

Editor's Note

The day following the massacre an SS war correspondent and a Totenkopf legal advisor visited the scene and photographs were also recorded as taken.

The massacre of Le Paradis still burns in the minds of many of Norwich and Norfolk’s war veterans.

Almost 100 Royal Norfolks were mown down after surrendering to the German SS on the withdrawal to Dunkirk in 1940.

Two badly wounded survivors helped to bring the officer behind the atrocity to the gallows.

Both are now dead. But they and the massacre victims will be remembered shortly when members of the Dunkirk Veterans Association leave Norwich for their annual Pilgrimage to the scene.

The black and white print will be presented to the local French mayor as a poignant reminder of a wartime episode recalled today by the EEN.

* * *

CAPTURED British soldiers, some clearly wounded, are marched at gunpoint by German SS troops past a damage barn on a sunny French day.

Shortly afterwards, their bodies lie under the same blistering sun, riddled by the bitter hail of machine gun fire.

The pictures on this page bear witness to the wartime atrocity which stole so many of Norfolk’s sons, Le Paradis.

The graphic study of the Royal Norfolks being marched off at gunpoint was taken by a young SS soldier and came to light a few years ago.

But the blurred snapshot of the barn and the bodies, which can just be seen in the middle ground, adds an even more tangible reality to the tortuous memory of the massacre story.

UNCLEAR

It has never been published before and its origin is unclear. What is certain, however, is that the French man or woman who took it faced violent retribution from the conquering Nazis if found out. That may explain the poor quality, a result of the likely haste in which the scene was photographed.

The picture has arrived in Norfolk via the High Wycombe branch of the Dunkirk Veterans’ Association, where Bert Pooley, one to the two Le Paradis survivors, was a member.

It has been sent to the association’s Norfolk branch secretary, Stan Baines, of Eastern Road Thorpe, after being sent some time ago to Mr. Pooley from an unknown correspondent in France.

Both branches are currently organising this year’s pilgrimage, at which the picture will be presented to a French civic party in a ceremony at the massacre memorial site. It will be attended by Connie, the wife of Mr. Pooley, and also Dennis, the son of the other survivor, Bill O’Callaghan, from Dereham.

As a commemorative symbol, the picture is priceless. It’s value as a record is underlined, however, by the courage of the photographer.

“The SS were in the village for a day or so afterwards so the picture would have been taken surreptitiously” said Dunkirk veteran Bill Priest, a retired teacher.

Mr. Priest of Beach Road, Gorleston suspects it was the work of the same French photographer who went on to take pictures of local people tending the graves of the Norfolks.

It was certainly taken in contrasting circumstances to the picture of the prisoners being marched to their deaths – a study now in Mr. Priest’s possession, and the work of a 17-year-old SS soldier, Herbert Brunnegger.

Now a successful hotelier, Herr Brunnegger is now in regular contact with Mr. Priest, whom he has told of the revulsion of other German troops on learning of the atrocity.

Herr Brunnegger, who says he left the scene before the shootings, has also told of the general assumption that the man responsible, Capt. Fritz Knoechlein, would be court martialled.

Yet retribution was not to come until 1949, when Knoechlein, the beast of the SS “Totenkopf” death’s head unit, was hanged for his ghastly crime – and then only because of the tenacity of the two Royal Norfolk survivors in pressing their case.

The horror of the atrocity, mirrored in these pictures, is amplified in the book, “The Vengeance of Private Pooley” by Cyril Jolly. Private Pooley told how the machine guns began to spit fire and disbelief overwhelmed him.

“For a few seconds the cries and shrieks of our stricken men drowned the cracking of the guns. Men fell like grass before a scythe. The invisible blade came nearer and then swept through me.

“I felt a searing pain in my leg and wrist and pitched forward engulfed in a red world of tearing agony. My scream of pain mingled with the cries of my mates, but even as I fell forward into a heap of dying men, the thought stabbed my brain. ‘If I ever get out of here the swine who did this will pay for it’”

Editor's Note

The day following the massacre an SS war correspondent and a Totenkopf legal advisor visited the scene and photographs were also recorded as taken.