Private Walter George Howlett

Private Walter George Howlett was batman* to Captain Charles Long. He was usually known by his second Christian name "George."

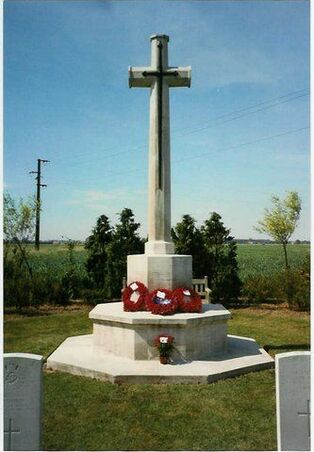

Whilst not one of the soldiers killed in the massacre, Private Howlett lost his life in Le Paradis on 27th May - the day of the massacre. It is likely he was killed as part of the rearguard action against the advancing German forces. It is likely that George is buried in an unmarked grave in Le Paradis Cemetery.

George was born on 3rd October, 1912. He joined the Royal Norfolk Regiment on 6th February, 1931 and signed up for seven years with the Colours and five years in the Army Reserves. At that time he was 18 years of age and working as an agricultural labourer.

He was posted to Gibraltar from March to 1st December 1937.

George was reported missing on 19th June 1940 three weeks after his now known death of 27th May 1940. He served a total of 9 years 363 days in the army. According to his army records George is buried at Hinges in France.

His death had a profound affect on Captain Long who admitted "a great respect and liking" for Private Howlett.

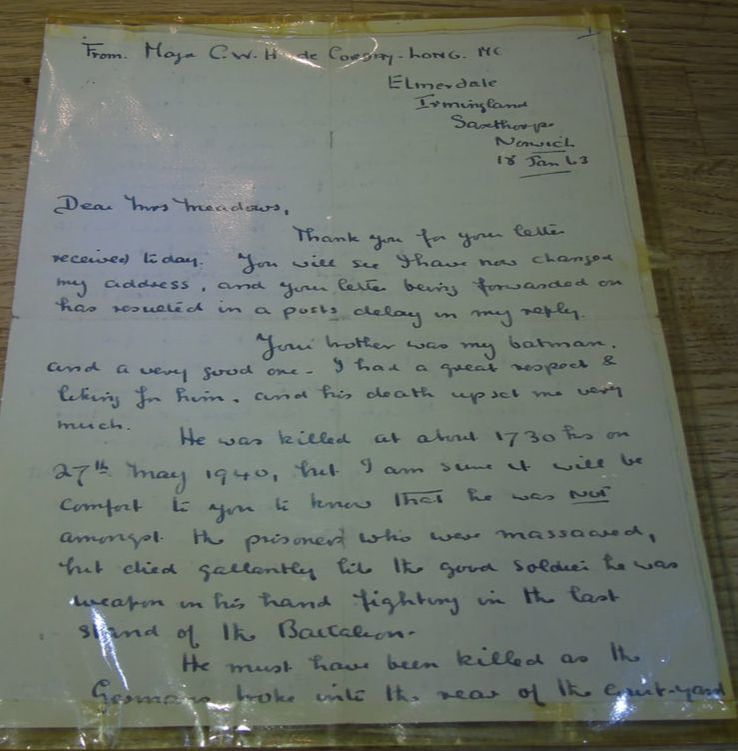

In 1963 - 23 years after the massacre - Captain Long wrote to Private Howlett's sister Ivy Meadows. That letter is now in the possession of Private Howlett's nephew Tony who lives in Palgrave in Suffolk. An image of the front page of the letter is reproduced below with a full transcript below that.

Whilst not one of the soldiers killed in the massacre, Private Howlett lost his life in Le Paradis on 27th May - the day of the massacre. It is likely he was killed as part of the rearguard action against the advancing German forces. It is likely that George is buried in an unmarked grave in Le Paradis Cemetery.

George was born on 3rd October, 1912. He joined the Royal Norfolk Regiment on 6th February, 1931 and signed up for seven years with the Colours and five years in the Army Reserves. At that time he was 18 years of age and working as an agricultural labourer.

He was posted to Gibraltar from March to 1st December 1937.

George was reported missing on 19th June 1940 three weeks after his now known death of 27th May 1940. He served a total of 9 years 363 days in the army. According to his army records George is buried at Hinges in France.

His death had a profound affect on Captain Long who admitted "a great respect and liking" for Private Howlett.

In 1963 - 23 years after the massacre - Captain Long wrote to Private Howlett's sister Ivy Meadows. That letter is now in the possession of Private Howlett's nephew Tony who lives in Palgrave in Suffolk. An image of the front page of the letter is reproduced below with a full transcript below that.

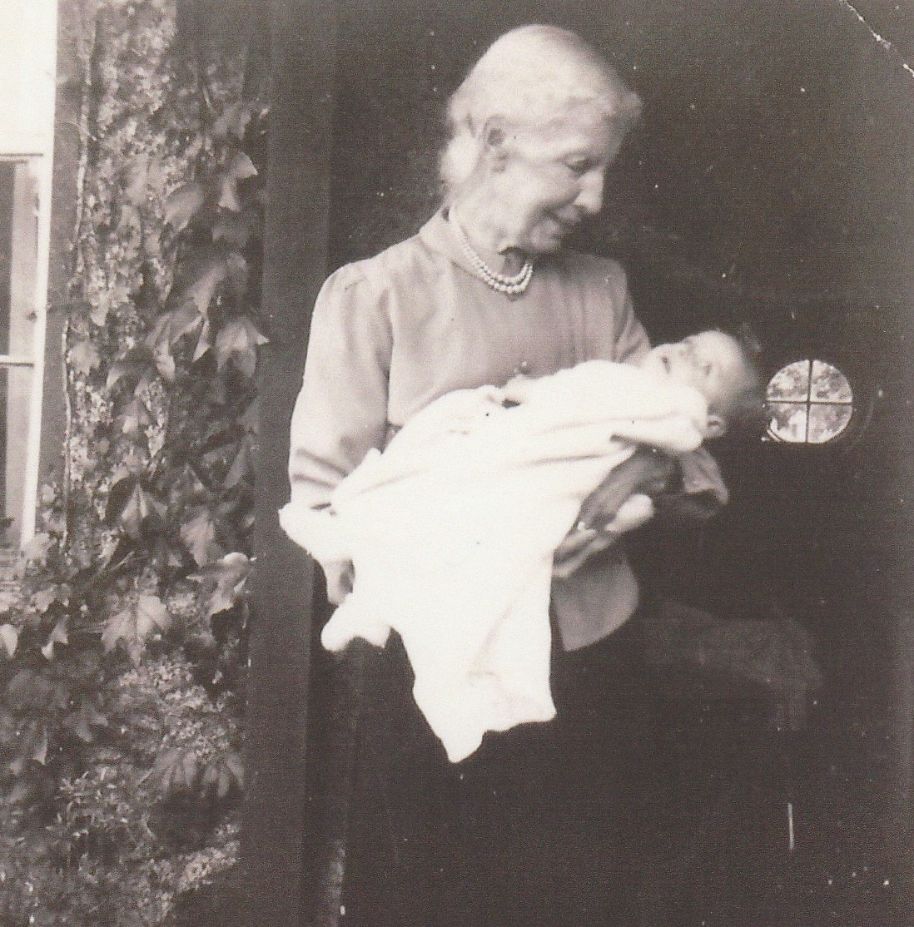

Captain Charles and Mrs Marjorie Long with their daughter Vicky. Both corresponded with the Howlett family. Today the two families are still in touch.

Captain Charles and Mrs Marjorie Long with their daughter Vicky. Both corresponded with the Howlett family. Today the two families are still in touch.

From Major C.W.H. de Corday Long MC

Dear Mrs Meadows

Thank you for your letter received today. You will see I have now changed my address and your letter being forwarded on has resulted in a posts delay in my reply.

Your brother was my batman and a very good one - I had a great respect and liking for him and his death upset me very much.

He was killed at about 17.30 hrs on 27th May 1940, but I am sure it will be comfort to you to know that he was not amongst the prisoners who were massacred, but died gallantly like the good soldier he was weapon in his hand fighting in the last stand of the Battalion.

He must have been killed as the Germans broke into the rear of the courtyard of the farm we were holding because I found him there the next morning. The German officer who captured me outside the farm on the edge of the road was - unlike most SS officers - a gentleman in our military sense of the word. He allowed me to take a small party of our men initially unguarded to search for possible wounded. It was when I was searching the farmyard that I found your brother. He still held his rifle and must have fallen fighting to the last.

I could not find his identity disc and was under the impression it had already been taken by the MO. Your brother's name did not appear on the list of missing which was sent to me for clarification by the War Office and of course that made me believe that his disc had already been cleared through the Red Cross and that the War Office knew what had happened.

I know my wife wrote to Mrs Howlett and told her whatever was possible and I am deeply sorry that you have been in ignorance of the details all this time.

During the whole of the afternoon of 27 May your brother had been with me. I remember he calmly(??) knelt at a window and fired at the advancing enemy and then came in and boiled a kettle and made tea. I remember him remarking that as it was getting on for 4 o'clock it was time for tea in spite of the enemy. He did not appear to be at all worried about the situation and was amazingly cheerful. In point of fact he always was under all circumstances.

Some days before we had been fighting heavily near Tournai. I mentioned that I could not find my water bottle. Just at that moment the enemy made a vicious attack and we all ran outside to man the defence of the HQ. There was a tremendous amount of shelling and when we came inside again I could not find your brother. The CO gave me permission to search for him outside - a soldier (I have forgotten his name), a friend of your brother, asked if he could volunteer to come to look for as he said "Old George." He and I went out and looked everywhere, but we could not find him. I was very much afraid he had been hit by shell fire and fallen in the lake. However, about half an hour later, he appeared, carrying my water bottle and apologising for being so long! He had actually gone into the open through heavy fire to a position he and I had been in almost half a mile away to look for my water bottle because he thought I might have left it there, and I had. So you see his ideas of duty were very firm, and his gallantry great.

He was a very worthy member of a fine Battalion and I can assure you I never forget him. He always went with me on all patrols and so on and I had the greatest confidence in him at all times.

I do hope the information I have been able to give to you has been what you wanted.

Those days were long ago and I have been soldiering in all parts of the world since then. It is difficult to remember everything that happened, but if there are more things you want to know please write to me and I will answer them to the best of my ability.

Yours Sincerely

Charles de Corday Long

Dear Mrs Meadows

Thank you for your letter received today. You will see I have now changed my address and your letter being forwarded on has resulted in a posts delay in my reply.

Your brother was my batman and a very good one - I had a great respect and liking for him and his death upset me very much.

He was killed at about 17.30 hrs on 27th May 1940, but I am sure it will be comfort to you to know that he was not amongst the prisoners who were massacred, but died gallantly like the good soldier he was weapon in his hand fighting in the last stand of the Battalion.

He must have been killed as the Germans broke into the rear of the courtyard of the farm we were holding because I found him there the next morning. The German officer who captured me outside the farm on the edge of the road was - unlike most SS officers - a gentleman in our military sense of the word. He allowed me to take a small party of our men initially unguarded to search for possible wounded. It was when I was searching the farmyard that I found your brother. He still held his rifle and must have fallen fighting to the last.

I could not find his identity disc and was under the impression it had already been taken by the MO. Your brother's name did not appear on the list of missing which was sent to me for clarification by the War Office and of course that made me believe that his disc had already been cleared through the Red Cross and that the War Office knew what had happened.

I know my wife wrote to Mrs Howlett and told her whatever was possible and I am deeply sorry that you have been in ignorance of the details all this time.

During the whole of the afternoon of 27 May your brother had been with me. I remember he calmly(??) knelt at a window and fired at the advancing enemy and then came in and boiled a kettle and made tea. I remember him remarking that as it was getting on for 4 o'clock it was time for tea in spite of the enemy. He did not appear to be at all worried about the situation and was amazingly cheerful. In point of fact he always was under all circumstances.

Some days before we had been fighting heavily near Tournai. I mentioned that I could not find my water bottle. Just at that moment the enemy made a vicious attack and we all ran outside to man the defence of the HQ. There was a tremendous amount of shelling and when we came inside again I could not find your brother. The CO gave me permission to search for him outside - a soldier (I have forgotten his name), a friend of your brother, asked if he could volunteer to come to look for as he said "Old George." He and I went out and looked everywhere, but we could not find him. I was very much afraid he had been hit by shell fire and fallen in the lake. However, about half an hour later, he appeared, carrying my water bottle and apologising for being so long! He had actually gone into the open through heavy fire to a position he and I had been in almost half a mile away to look for my water bottle because he thought I might have left it there, and I had. So you see his ideas of duty were very firm, and his gallantry great.

He was a very worthy member of a fine Battalion and I can assure you I never forget him. He always went with me on all patrols and so on and I had the greatest confidence in him at all times.

I do hope the information I have been able to give to you has been what you wanted.

Those days were long ago and I have been soldiering in all parts of the world since then. It is difficult to remember everything that happened, but if there are more things you want to know please write to me and I will answer them to the best of my ability.

Yours Sincerely

Charles de Corday Long

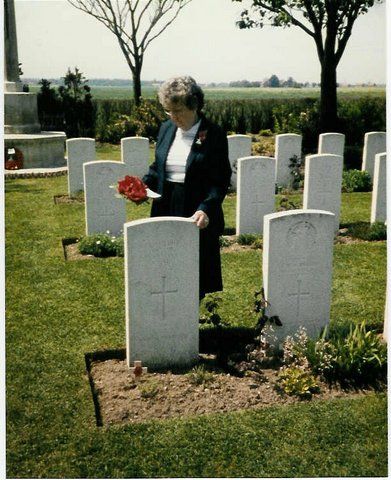

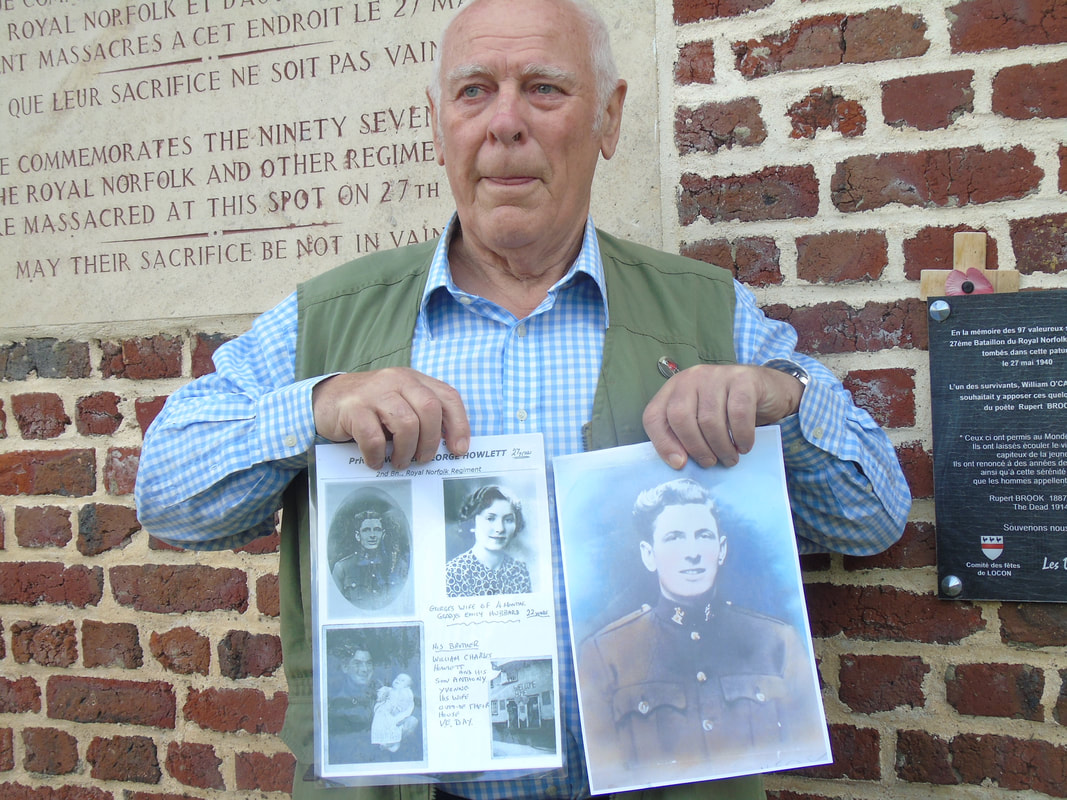

George's nephew Tony told us that his "uncle" had been firing at the Germans through a window of the farmhouse and was alongside a Private Arthur Betts. George had a brother and sister. Ivy Howlett became Ivy Meadows and William Charles "Dick" Howlett became Tony Howlett's father. Tony says that his father "very rarely" talked about the war. Tony and his wife have "adopted" one of the headstones in Le Paradis Churchyard as a symbol of George Howlett. It is one of the unnamed graves and Tony is pictured beside it above.

Walter George Howlett - Marriage and Service

Walter George Howlett

Walter George Howlett

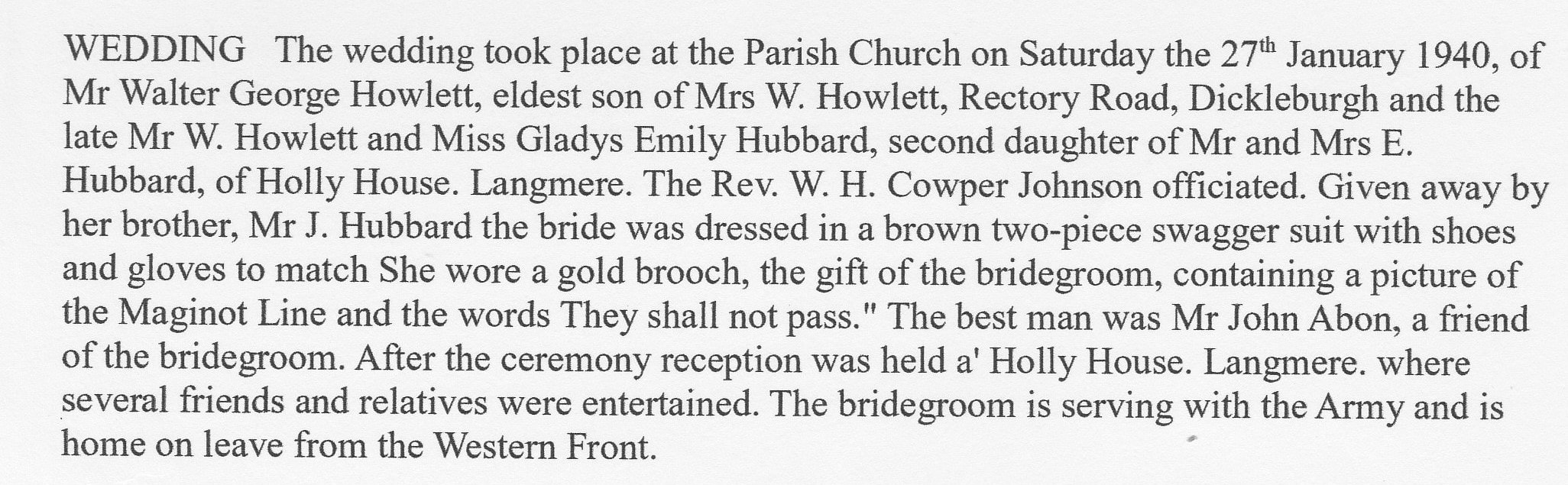

Just four months before George died fighting in the area around Le Paradis, he married his childhood sweetheart Gladys Emily Hubbard. George was granted 10 days' leave in the UK from 25th January, 1940, and he married Gladys on 27th January in Dickleburgh whilst on leave. He was also granted 10 days' leave in the UK from 6th April, 1940, and re-joined his unit on 18th April, 1940

The report of the wedding below is taken from the Diss Express newspaper of February 2nd, 1940. George and Gladys enjoyed a joint wedding with George's sister Ivy who was married to Ronnie Meadows.

Below the press report is a photograph of Gladys' gold brooch. The motto "On Ne Passe Pas" referred to the Maginot Line. On Christmas Eve, 1939, the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Norfolks were on their way by train to Metz, travelling all night and finally arriving at Metz early on Christmas afternoon. They then travelled several miles over roads made treacherous by snow and ice before taking up their position in front of the Maginot Line.

There is also a letter with regard to Walter Howlett's medals (click on the images to enlarge them).

The report of the wedding below is taken from the Diss Express newspaper of February 2nd, 1940. George and Gladys enjoyed a joint wedding with George's sister Ivy who was married to Ronnie Meadows.

Below the press report is a photograph of Gladys' gold brooch. The motto "On Ne Passe Pas" referred to the Maginot Line. On Christmas Eve, 1939, the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Norfolks were on their way by train to Metz, travelling all night and finally arriving at Metz early on Christmas afternoon. They then travelled several miles over roads made treacherous by snow and ice before taking up their position in front of the Maginot Line.

There is also a letter with regard to Walter Howlett's medals (click on the images to enlarge them).

After George's death, Gladys met and married Jack Harold Everitt and they had a son Michael H. Everitt who takes up the story.

"In late 1941 my father was sent to Pulham Air Station to help dismantle shed Number One, one of the big airship hangars, and the support buildings which had once held the big airships. In the local area, the airships were known as the Pulham Pigs.... On the airfield father got talking to a man who at the time worked on the airfield, asking if he knew where he could get board and lodgings. The man, who was later to become our grandfather, said he could put him up. That's how my father met my mother to be. They married in February 1942 and I was born in July.

"Mother left school at just 14 and went straight into service at one of the local big houses as cook's maid. She later became the cook in charge of the kitchen and worked at several large houses in the area.

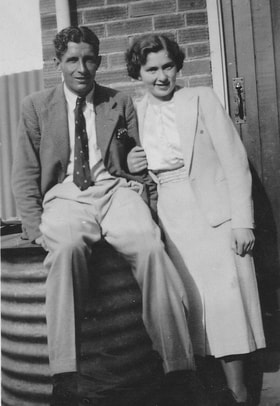

"On the 27th January, 1940, aged 22, she married her childhood sweetheart George, a local lad who was at the time in the army with the 2nd Battalion Royal Norfolk Regiment. Not long after they were married George was sent back to France with the British Expeditionary Force.

"We as a family have always known that our mother was married before she met our father, but have very little details about it. In all of our mother's life she never got over the loss of George, her childhood sweetheart. He was never spoken of, as I can only think it was far too painful for her. It was not until she passed away in 2012 that we found a small tin box that contained photos of George and her outside Tony Howlett's grandparents' house at 17 Rectory Road (Dickleburgh). Also we found letters from Major Long's wife together with some old newspaper cuttings of that date, about missing soldiers and about the massacre. We also found hidden in her house a larger photo of a person we did not know, who was not a member of our family. Later, when we were able to match the large photo with the contents of the small tin we then realised who it was. So we all thought it would be a good idea to place the photo of George alongside our mother in her coffin so at last at least they were together again.

Below are photographs of George and Gladys from Michael Everitt's collection and reproduced with his kind permission and below that is a series of letters sent to Gladys firstly when George was reported missing and then after it was confirmed that he had died.

"In late 1941 my father was sent to Pulham Air Station to help dismantle shed Number One, one of the big airship hangars, and the support buildings which had once held the big airships. In the local area, the airships were known as the Pulham Pigs.... On the airfield father got talking to a man who at the time worked on the airfield, asking if he knew where he could get board and lodgings. The man, who was later to become our grandfather, said he could put him up. That's how my father met my mother to be. They married in February 1942 and I was born in July.

"Mother left school at just 14 and went straight into service at one of the local big houses as cook's maid. She later became the cook in charge of the kitchen and worked at several large houses in the area.

"On the 27th January, 1940, aged 22, she married her childhood sweetheart George, a local lad who was at the time in the army with the 2nd Battalion Royal Norfolk Regiment. Not long after they were married George was sent back to France with the British Expeditionary Force.

"We as a family have always known that our mother was married before she met our father, but have very little details about it. In all of our mother's life she never got over the loss of George, her childhood sweetheart. He was never spoken of, as I can only think it was far too painful for her. It was not until she passed away in 2012 that we found a small tin box that contained photos of George and her outside Tony Howlett's grandparents' house at 17 Rectory Road (Dickleburgh). Also we found letters from Major Long's wife together with some old newspaper cuttings of that date, about missing soldiers and about the massacre. We also found hidden in her house a larger photo of a person we did not know, who was not a member of our family. Later, when we were able to match the large photo with the contents of the small tin we then realised who it was. So we all thought it would be a good idea to place the photo of George alongside our mother in her coffin so at last at least they were together again.

Below are photographs of George and Gladys from Michael Everitt's collection and reproduced with his kind permission and below that is a series of letters sent to Gladys firstly when George was reported missing and then after it was confirmed that he had died.

Letters to Gladys

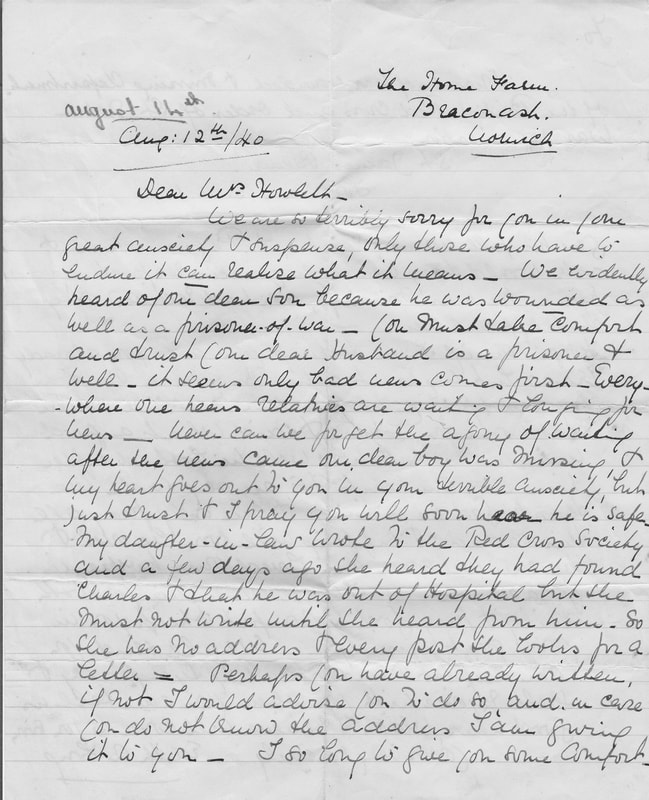

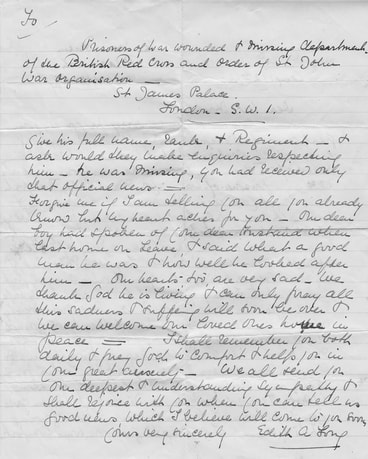

Letter from Edith Long, the Home Farm, Bracon Ash - Captain Long's mother to Gladys knowing that George is missing. It is dated August 12th, 1940.

Dear Mrs Howlett

We are so terribly sorry for you in your great anxiety and suspense, only those who have to endure it can realise what it means. We evidently heard of our dear son because he was wounded as well as a prisoner-of-war. You must take comfort and trust your dear husband is a prisoner and well, it seems only bad news comes first. Everywhere one hears relatives are waiting and longing for news. Never can we forget the agony of waiting after the news came our dear boy was missing, and my heart goes out to you in your terrible anxiety, but just trust and I pray you will soon hear he is safe. My daughter-in–law wrote to the Red Cross Society and a few days ago she heard they had found Charles and that he was out of hospital but she must not write until she heard from him. So now she has no address and every post she looks for a letter. Perhaps you have already written, if not I would advise you to do so, and in case you do not know the address I’m giving it to you. I so long to give you some comfort.

To

Prisoners of War Wounded and Missing Department of the British Red Cross and Order of St John War Organisation.

St James Palace

London SW1

Give his full name, rank and Regiment ask would they make enquiries respecting him – he was missing, you had received only that official news.

Forgive me if I am telling you all you already know but my heart aches for you. Our dear boy had spoken of your dear husband when last home on Leave and said what a good man he was and how well he looked after him. Our hearts, too, are very sad. We thank God he is living and can only pray all this sadness and suffering will soon be over and we can welcome our loved ones home in peace.

I shall remember you both daily and pray God to comfort and help you in your great anxiety. We all send you our deepest and understanding sympathy and shall rejoice with you when you can tell us the good news which I believe will come to you soon.

Yours very sincerely

Edith A Long

Dear Mrs Howlett

We are so terribly sorry for you in your great anxiety and suspense, only those who have to endure it can realise what it means. We evidently heard of our dear son because he was wounded as well as a prisoner-of-war. You must take comfort and trust your dear husband is a prisoner and well, it seems only bad news comes first. Everywhere one hears relatives are waiting and longing for news. Never can we forget the agony of waiting after the news came our dear boy was missing, and my heart goes out to you in your terrible anxiety, but just trust and I pray you will soon hear he is safe. My daughter-in–law wrote to the Red Cross Society and a few days ago she heard they had found Charles and that he was out of hospital but she must not write until she heard from him. So now she has no address and every post she looks for a letter. Perhaps you have already written, if not I would advise you to do so, and in case you do not know the address I’m giving it to you. I so long to give you some comfort.

To

Prisoners of War Wounded and Missing Department of the British Red Cross and Order of St John War Organisation.

St James Palace

London SW1

Give his full name, rank and Regiment ask would they make enquiries respecting him – he was missing, you had received only that official news.

Forgive me if I am telling you all you already know but my heart aches for you. Our dear boy had spoken of your dear husband when last home on Leave and said what a good man he was and how well he looked after him. Our hearts, too, are very sad. We thank God he is living and can only pray all this sadness and suffering will soon be over and we can welcome our loved ones home in peace.

I shall remember you both daily and pray God to comfort and help you in your great anxiety. We all send you our deepest and understanding sympathy and shall rejoice with you when you can tell us the good news which I believe will come to you soon.

Yours very sincerely

Edith A Long

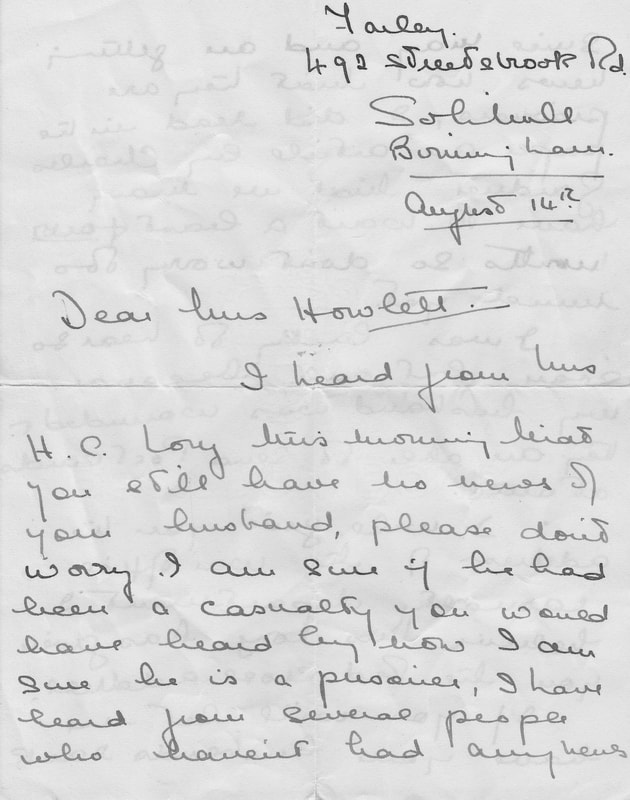

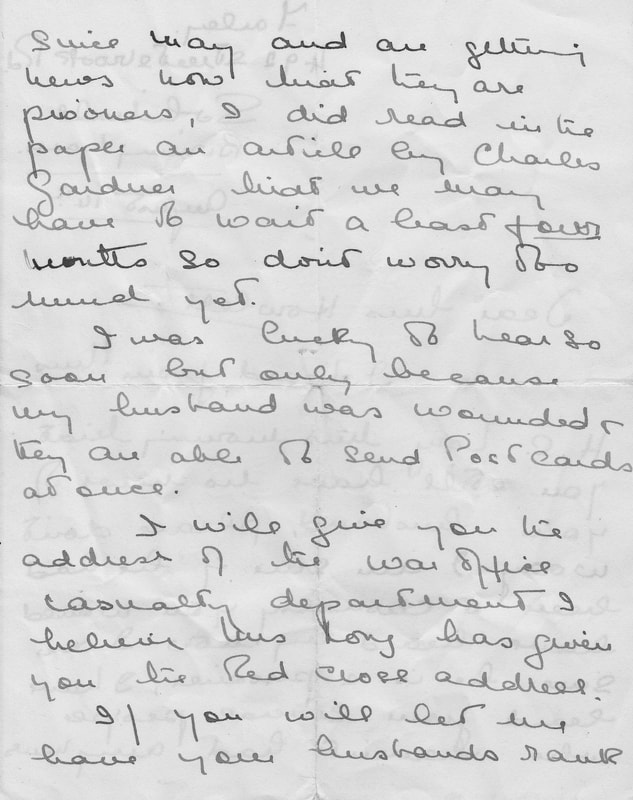

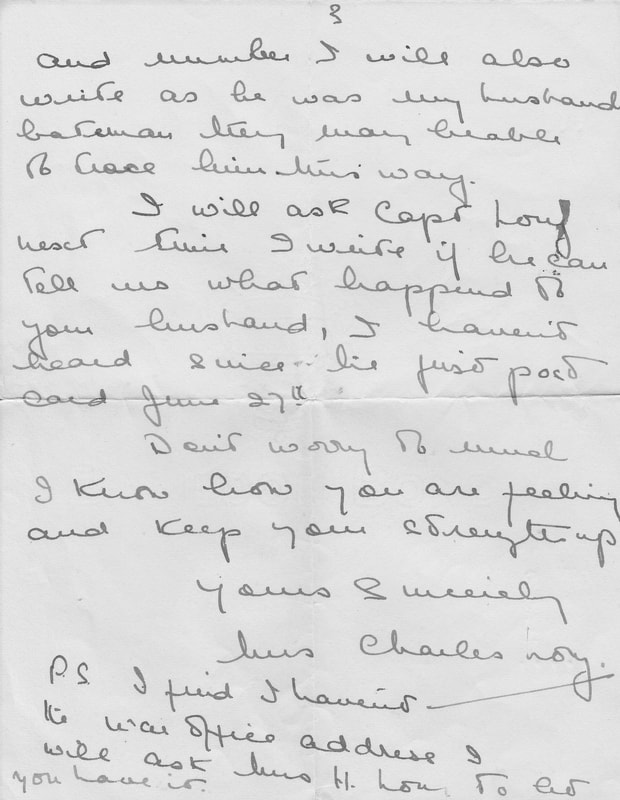

Letter from Mrs Charles Long, wife of Captain Long to Gladys Howlett when George is missing. It is dated August 14th, 1940. It was sent from 492, Streetsbrook Road, Solihull.

Dear Mrs Howlett,

I heard from Mrs H C Long this morning that you still have no news of your husband, please don’t worry. I am sure if he had been a casualty you would have heard by now. I am sure he is a prisoner, I have heard from several people who haven’t had any news since May and are getting news now that they are prisoners, I did read in the paper an article by Charles Gardner that we may have to wait at least four months so don’t worry too much yet.

I was lucky to hear so soon but only because my husband was wounded and they are able to send post cards at once.

I will give you the address of the war office casually department I believe Mrs Long has given you the Red Cross address.

If you will let me have your husbands rank and number I will also write as he was my husband’s batman they may be able to trace him this way.

I will ask Capt. Long next time I write if he can tell us what happened to your husband, I haven’t heard since his first post card June 27th.

Don’t worry too much I know how you are feeling and keep your strength up.

Yours sincerely

Mrs Charles Long

P.S. I find I haven’t the war office address I will ask Mrs H Long to let you have it.

Dear Mrs Howlett,

I heard from Mrs H C Long this morning that you still have no news of your husband, please don’t worry. I am sure if he had been a casualty you would have heard by now. I am sure he is a prisoner, I have heard from several people who haven’t had any news since May and are getting news now that they are prisoners, I did read in the paper an article by Charles Gardner that we may have to wait at least four months so don’t worry too much yet.

I was lucky to hear so soon but only because my husband was wounded and they are able to send post cards at once.

I will give you the address of the war office casually department I believe Mrs Long has given you the Red Cross address.

If you will let me have your husbands rank and number I will also write as he was my husband’s batman they may be able to trace him this way.

I will ask Capt. Long next time I write if he can tell us what happened to your husband, I haven’t heard since his first post card June 27th.

Don’t worry too much I know how you are feeling and keep your strength up.

Yours sincerely

Mrs Charles Long

P.S. I find I haven’t the war office address I will ask Mrs H Long to let you have it.

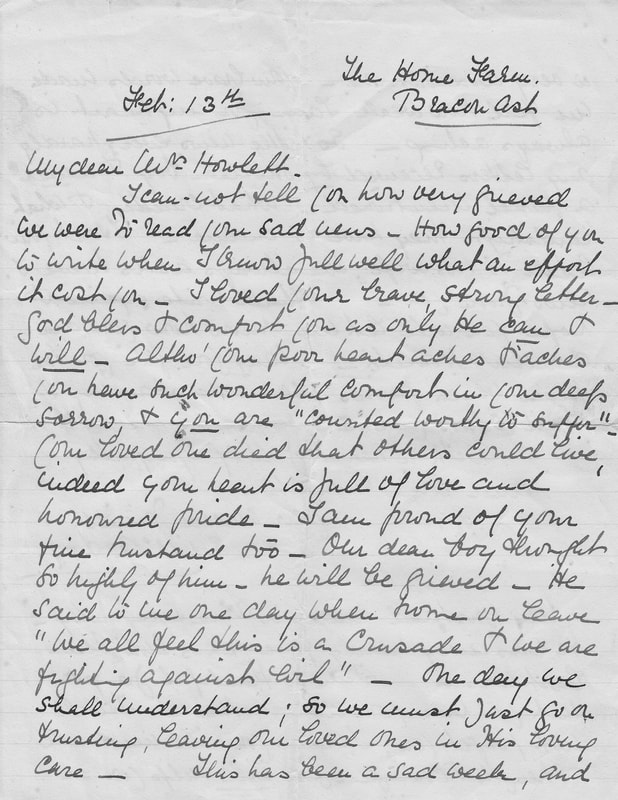

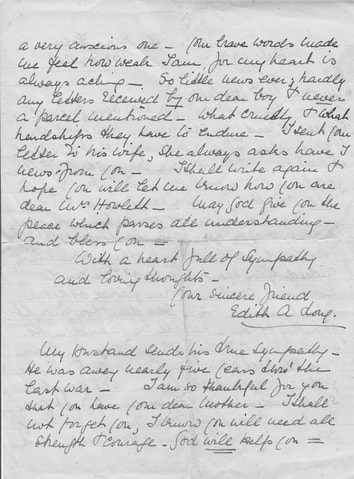

Letter from Edith Long, mother of Captain Charles Long to Gladys Howlett - sent on February 13th, 1941.

My Dear Mrs Howlett,

I cannot tell you how very grieved we were to read your sad news. How good of you to write when I know full well what an effort it cost you. I loved your brave, strong letter. God bless and comfort you as only He can and will. Althou’ your poor heart aches and aches you have such a wonderful comfort in your deep sorrow and you are “counted worthy to suffer”. Your loved one died that others could live, indeed your heart is full of love and honoured pride. I am proud of your fine husband too. Our dear boy thought so highly of him - he will be grieved. He said to me one day when home on leave “We all feel this is a Crusade and we are fighting against evil”. One day we shall understand; so we must just go on trusting, leaving our loved ones in His loving care. This has been a sad week, and a very anxious one. Your brave words made me feel how weak I am, for my heart is always aching. So little news ever; hardly any letters received by our dear boy and never a parcel mentioned. What cruelty and what hardships they have to endure. I sent your letter to his wife, she always asks have I news from you. I shall write again and hope you will let me know how you are dear Mrs Howlett. May God give you the peace which passes all understanding and bless you.

With a heart full of sympathy and loving thoughts,

Your sincere friend

Edith A Long

My husband sends his true sympathy. He was away nearly five years thro’ the last war. I am so thankful for you that you have your dear mother. I shall not forget you, I know you will need all strength and courage. God will help you.

My Dear Mrs Howlett,

I cannot tell you how very grieved we were to read your sad news. How good of you to write when I know full well what an effort it cost you. I loved your brave, strong letter. God bless and comfort you as only He can and will. Althou’ your poor heart aches and aches you have such a wonderful comfort in your deep sorrow and you are “counted worthy to suffer”. Your loved one died that others could live, indeed your heart is full of love and honoured pride. I am proud of your fine husband too. Our dear boy thought so highly of him - he will be grieved. He said to me one day when home on leave “We all feel this is a Crusade and we are fighting against evil”. One day we shall understand; so we must just go on trusting, leaving our loved ones in His loving care. This has been a sad week, and a very anxious one. Your brave words made me feel how weak I am, for my heart is always aching. So little news ever; hardly any letters received by our dear boy and never a parcel mentioned. What cruelty and what hardships they have to endure. I sent your letter to his wife, she always asks have I news from you. I shall write again and hope you will let me know how you are dear Mrs Howlett. May God give you the peace which passes all understanding and bless you.

With a heart full of sympathy and loving thoughts,

Your sincere friend

Edith A Long

My husband sends his true sympathy. He was away nearly five years thro’ the last war. I am so thankful for you that you have your dear mother. I shall not forget you, I know you will need all strength and courage. God will help you.

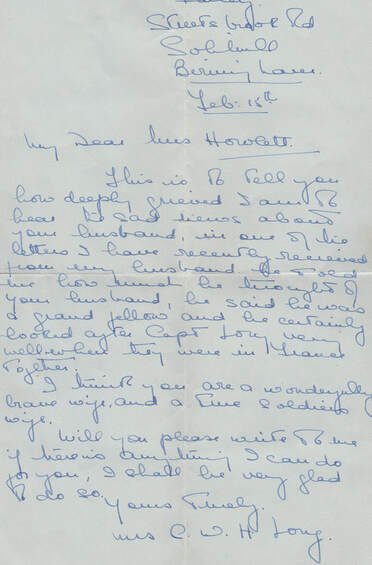

Letter from Mrs Charles Long (pictured opposite) to Gladys Howlett - sent on February 15th, 1941. Mrs Long's first name was Marjorie.

My Dear Mrs Howlett,

This is to tell you how deeply grieved I am to hear the sad news about your husband, in one of the letters I have recently received from my husband. He told me how much he thought of your husband, he said he was a grand fellow and he certainly looked after Capt. Long very well when they were in France together.

I think you are a wonderfully brave wife and a true soldier’s wife.

Will you please write to me if there is anything I can do for you, I shall be very glad to do so.

Yours truly

Mrs C. W. H. Long

My Dear Mrs Howlett,

This is to tell you how deeply grieved I am to hear the sad news about your husband, in one of the letters I have recently received from my husband. He told me how much he thought of your husband, he said he was a grand fellow and he certainly looked after Capt. Long very well when they were in France together.

I think you are a wonderfully brave wife and a true soldier’s wife.

Will you please write to me if there is anything I can do for you, I shall be very glad to do so.

Yours truly

Mrs C. W. H. Long

Gladys' Story

Gladys' life has been well documented thanks to the efforts of her son Michael Everitt.

"My mother was born into a poor family at Shimpling in Norfolk on 28th August, 1918. She was the middle child of 13 children. Her parents lived in a very small thatched farm labourer's cottage with just one room upstairs and one down. In the bedroom upstairs there was a great old large king size bed which at times would have eight children sleeping in it. To get them all into it they had to sleep across the bed, top to tail. They had only one blanket, one sheet plus three army great coats over the top. The two youngest children slept downstairs with my grandparents in the two large bottom drawers taken out of a large chest of drawers.

In 1925 when our mother was about seven years old, my grandfather managed to purchase a five-bedroom house called "Holly House" for £500. This was in the countryside at Langmere near Dickleburgh - about four miles from Shimpling. It was an idyllic place with farms all around plus a blacksmith's and carpenter's shop across the road where they made and repaired everything for all the farmers, from shoeing horses to making stack ladders, even building whole hay carts (when I was a small lad I would run across to the blacksmith's shop, stand on a box and pump the bellows on the furnace for the blacksmith when he was shoeing the horses).

When it came to the day of the move to the new house our grandfather borrowed a horse and a small cart from a local farmer onto which they put all their worldly goods. They then set off to the new house with our grandfather leading the way with the horse and our grandmother sitting on the tailboard with two very young children in her arms, the rest of the children having to walk behind the cart. Some of them had no shoes and one of the older boys had the job of pushing the pram inside of which was the only oil light lamp they had, this was all wrapped up and covered with sacking so it didn't get damaged. About halfway to the new house some of the younger children started playing up, saying 'are we nearly there yet' and 'how much further do we have to go to the new house,' but they had to keep walking encouraged by the older children.

When at last they got to the new house, my mother said that she and the rest of the children just couldn't believe their eyes - the house was so big. To them it looked as big as Buckingham Palace after coming from such a very small cottage.

Holly House stood on a large plot of land, but it had no electric, so everything after dark was done by candlelight or a Tilley Lamp. There was no running water and drinking water came from a large well just outside the back kitchen door where a galvanised bucket was lowered mainly in the summer months to collect the water when the hand pump in the kitchen ran dry. In the summer months my grandmother would lower the large bucket halfway down into the well with the milk and butter in it to keep them cool (as a lad I always remember looking down the well and seeing big yellowy brown slugs about four inches or more long around the side of the well walls).

One of the first things our grandfather did when they moved into the house was to put a bell on the top of the pantry door, so if the children tried to sneak into the pantry to pinch food, the bell would ring to let our grandmother know.

The privy was outside attached to the side of the outhouse. Inside it was just a wide wooden plank with a round hole cut into it. Underneath was a large oval galvanised bucket, this our grandfather had to empty into a pre-dug hole up in the orchard each week. Later the older boys got that job and the girls got the job of cutting up old newspapers into squares then threading them onto a piece of string, hung inside on the privy door to use as a toilet paper.

"My mother was born into a poor family at Shimpling in Norfolk on 28th August, 1918. She was the middle child of 13 children. Her parents lived in a very small thatched farm labourer's cottage with just one room upstairs and one down. In the bedroom upstairs there was a great old large king size bed which at times would have eight children sleeping in it. To get them all into it they had to sleep across the bed, top to tail. They had only one blanket, one sheet plus three army great coats over the top. The two youngest children slept downstairs with my grandparents in the two large bottom drawers taken out of a large chest of drawers.

In 1925 when our mother was about seven years old, my grandfather managed to purchase a five-bedroom house called "Holly House" for £500. This was in the countryside at Langmere near Dickleburgh - about four miles from Shimpling. It was an idyllic place with farms all around plus a blacksmith's and carpenter's shop across the road where they made and repaired everything for all the farmers, from shoeing horses to making stack ladders, even building whole hay carts (when I was a small lad I would run across to the blacksmith's shop, stand on a box and pump the bellows on the furnace for the blacksmith when he was shoeing the horses).

When it came to the day of the move to the new house our grandfather borrowed a horse and a small cart from a local farmer onto which they put all their worldly goods. They then set off to the new house with our grandfather leading the way with the horse and our grandmother sitting on the tailboard with two very young children in her arms, the rest of the children having to walk behind the cart. Some of them had no shoes and one of the older boys had the job of pushing the pram inside of which was the only oil light lamp they had, this was all wrapped up and covered with sacking so it didn't get damaged. About halfway to the new house some of the younger children started playing up, saying 'are we nearly there yet' and 'how much further do we have to go to the new house,' but they had to keep walking encouraged by the older children.

When at last they got to the new house, my mother said that she and the rest of the children just couldn't believe their eyes - the house was so big. To them it looked as big as Buckingham Palace after coming from such a very small cottage.

Holly House stood on a large plot of land, but it had no electric, so everything after dark was done by candlelight or a Tilley Lamp. There was no running water and drinking water came from a large well just outside the back kitchen door where a galvanised bucket was lowered mainly in the summer months to collect the water when the hand pump in the kitchen ran dry. In the summer months my grandmother would lower the large bucket halfway down into the well with the milk and butter in it to keep them cool (as a lad I always remember looking down the well and seeing big yellowy brown slugs about four inches or more long around the side of the well walls).

One of the first things our grandfather did when they moved into the house was to put a bell on the top of the pantry door, so if the children tried to sneak into the pantry to pinch food, the bell would ring to let our grandmother know.

The privy was outside attached to the side of the outhouse. Inside it was just a wide wooden plank with a round hole cut into it. Underneath was a large oval galvanised bucket, this our grandfather had to empty into a pre-dug hole up in the orchard each week. Later the older boys got that job and the girls got the job of cutting up old newspapers into squares then threading them onto a piece of string, hung inside on the privy door to use as a toilet paper.

Press Cuttings

The following press cuttings are from the collection of Michael Everitt. Some are relevant to Le Paradis and others are general cuttings. They were collected by Gladys. One depicts Dickleburgh taken from the now defunct Norwich Mercury and another a list of Norfolk men missing.

Other Family Photographs

The photographs below show George's brother and sister "Dick" and Ivy during their school days. In the picture on the left, Ivy is in the middle row second from the right and in the picture on the right, "Dick" is in the centre of the group of three boys.

* Batman - A soldier assigned to a commissioned officer as a personal servant.

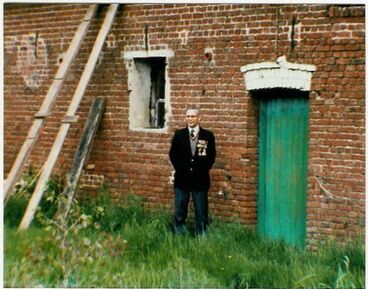

In 2022 George's nephew Tony Howlett made another pilgrimage to Le Paradis and the photographs below were taken alongside the barn wall.