Private Ernie Leggett

Ernest James "Ernie" Leggett was born in Clippesby on December 22nd, 1919, joining the 2nd Battalion The Royal Norfolk Regiment on ‘boy service’ in 1935 at the tender age of 15 as his daughter Sandra De Ville-Leggett remembers:

"I think he joined the army as a way of escaping poverty as it was tough going in the 1930s. My grandparents worked the land and there wasn't much in the way of work. The 1930s was a time of the Great Depression.

"My father was an excellent shot from an early age and would be paid to shoot vermin. In those days you could get entry to a cinema in exchange for a rabbit skin. I think he took to army life like a duck to water as it gave him three square meals a day.

Ernie was a rifle marksman and also fired Bren guns. He was also an excellent bandsman, excelling at the drum and bugle.

Ernie was a popular member of the Royal Norfolks in what he considered to be "a band of brothers" and a closely knit community.

He spent time training in Gibraltar before being sent to engage the enemy in 1939, ending up on the Dyle Line in 1940. He experienced the heroic and fighting retreat of his Battalion before being seriously wounded at the defence of the River Escaut whilst holed up in a cement works. As a result of his injuries Ernie was repatriated.

"I remember him as a military man through and through - strong and loyal. But he wasn't a man who easily showed his emotion and it was a long time before I understood what he had gone through. I remember when I was a child he would wake up screaming in the night. We just accepted that he suffered nightmares," Sandra said.

At times knowing that he had survived the war when so many of his colleagues died led to Ernie suffering feelings of guilt:

Ernest James "Ernie" Leggett was born in Clippesby on December 22nd, 1919, joining the 2nd Battalion The Royal Norfolk Regiment on ‘boy service’ in 1935 at the tender age of 15 as his daughter Sandra De Ville-Leggett remembers:

"I think he joined the army as a way of escaping poverty as it was tough going in the 1930s. My grandparents worked the land and there wasn't much in the way of work. The 1930s was a time of the Great Depression.

"My father was an excellent shot from an early age and would be paid to shoot vermin. In those days you could get entry to a cinema in exchange for a rabbit skin. I think he took to army life like a duck to water as it gave him three square meals a day.

Ernie was a rifle marksman and also fired Bren guns. He was also an excellent bandsman, excelling at the drum and bugle.

Ernie was a popular member of the Royal Norfolks in what he considered to be "a band of brothers" and a closely knit community.

He spent time training in Gibraltar before being sent to engage the enemy in 1939, ending up on the Dyle Line in 1940. He experienced the heroic and fighting retreat of his Battalion before being seriously wounded at the defence of the River Escaut whilst holed up in a cement works. As a result of his injuries Ernie was repatriated.

"I remember him as a military man through and through - strong and loyal. But he wasn't a man who easily showed his emotion and it was a long time before I understood what he had gone through. I remember when I was a child he would wake up screaming in the night. We just accepted that he suffered nightmares," Sandra said.

At times knowing that he had survived the war when so many of his colleagues died led to Ernie suffering feelings of guilt:

Memories of Ernie as A Father

The cement works where Ernie was seriously injured.

The cement works where Ernie was seriously injured.

"As a child we grew up (Sandra has a sister and brother) with a father who could be rather distant some of the time.

"When he was injured, he thought he was going to die. After surviving he looked on every day as a bonus. I wish now that I'm older that I could have understood earlier just what he had gone through. At first he didn't talk about the war, but later he began to open up a bit. Gradually I began to piece together what had happened to him. Eventually he told me about George Gristock*, Sandra added.

Ernie was told by doctors that his injuries sustained in the war would limit his movement later in life and this proved to be true, although he continued to be hugely active

After leaving the army, Ernie continued his work in uniform by firstly joining the Military Police and then becoming a police officer with Norfolk Constabulary and then working for Loose's Department store in Norwich.

He was a very active member of the Dunkirk Veterans' Association, becoming editor of their magazine and treasurer of the local group. He was also a steward at his local church. He regularly visited Northern France to remember his fallen comrades.

Ernie Leggett died in February 2001 and is buried in Clippesby Churchyard in the grounds of a church in which he was Christened and married.

Prior to his death in February, 2001, Ernie wrote a book ‘A Boyhood in the Fleggs’ which gives an insight into his life.

* - Private Ernie Leggett witnessed the heroics of CSM George Gristock from the cement works on the Escaut before being seriously wounded by a mortar shell.

"When he was injured, he thought he was going to die. After surviving he looked on every day as a bonus. I wish now that I'm older that I could have understood earlier just what he had gone through. At first he didn't talk about the war, but later he began to open up a bit. Gradually I began to piece together what had happened to him. Eventually he told me about George Gristock*, Sandra added.

Ernie was told by doctors that his injuries sustained in the war would limit his movement later in life and this proved to be true, although he continued to be hugely active

After leaving the army, Ernie continued his work in uniform by firstly joining the Military Police and then becoming a police officer with Norfolk Constabulary and then working for Loose's Department store in Norwich.

He was a very active member of the Dunkirk Veterans' Association, becoming editor of their magazine and treasurer of the local group. He was also a steward at his local church. He regularly visited Northern France to remember his fallen comrades.

Ernie Leggett died in February 2001 and is buried in Clippesby Churchyard in the grounds of a church in which he was Christened and married.

Prior to his death in February, 2001, Ernie wrote a book ‘A Boyhood in the Fleggs’ which gives an insight into his life.

* - Private Ernie Leggett witnessed the heroics of CSM George Gristock from the cement works on the Escaut before being seriously wounded by a mortar shell.

His involvement in this action is best summed up by an article which was printed in The Sun Newspaper on 15th May, 2000, and which reads as follows:

"Bren Gunner Ernie Leggett served with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment after joining as a drummer boy at 19 in 1939. He is now 80 and living in Norwich. Only an enemy shell which almost blew him to bits, spared the infantryman the fate of his comrades as they tried to keep Hitler’s Army from reaching Dunkirk. They were cold bloodedly murdered in one of the most infamous massacres of the war.

Ernie Leggett recalls

“We went up as far as the River Dyle in the Netherlands and saw some terrible sights coming back because people were being bombed and strafed by Stuka planes.

Refugees were being killed and the towns were being flattened.

Water and fires were everywhere and the dead were lying in the street.

The Germans made lots of attacks against us on May 21, 22 and 23.

As I was a marksman on a Bren gun, I was able to cause quite a lot of havoc among them but they decimated us.

Out of my company of 120 men, I was one of only eight left by May 24. I was hit by a trench mortar and thrown up on to the roof of the cement factory where we had our positions.

I received severe wounds to my left leg and a big piece of shrapnel went in through my left buttock and out through my groin. My back was fractured and I had no feeling from the waist down.

I just lay there in a pool of blood and the others took me down and laid me in the lee of a railway line. My mates could not have done any more.

I couldn’t move my legs at all. I was crawling along the railway line – no clothes, my finger nails worn down to the bone – and a bomber appeared above me.

I could actually see the bomb doors open and a string of bombs fall. I was covered in earth three times in craters. The third time I managed to call out ‘Please, help me.’ I can’t remember any more until I felt my arms being pulled.

I recognised two drummers who had been in the band with me and another bandsman said ‘Bloody hell, it’s Ernie’. Then he said, ‘Bloody Hell, he’s had it.’

The next thing I knew I was looking up into the face of a medical officer and a Belgian nurse, who gave me a shot of morphine and I was put out.

For the next six or seven days I was travelling across Belgium and France in a hospital train and ambulances and finished up in the Dunkirk dunes.

I heard all the commotion and bombs being dropped before they got me on board a hospital ship.

Every so often the medical staff would come along and inject me with morphine which knocked me out until the next time I came around in terrible pain.

RUNNING

Our hospital ship, the St Julian, was painted brilliant white with a big red cross and couldn’t be mistaken, yet we were constantly bombed and strafed.

But if I had not been wounded I would now be in a cemetery with my mates. The seven left in my unit were transferred to Battalion headquarters in Le Paradis.

Just 99 of them held off a full SS Totenkopf Regiment but they were running out of ammo and it was useless to carry on so they had little choice but to surrender.

The first three who went out with a towel waving from a rifle were immediately shot down. The rest rushed out to cheers from the Germans and were taken prisoner.

During the afternoon of May 27th they were humiliated butted and struck. Their belonging were taken from them. They were marched along a road, turned left into a paddock and machine gunned. Only two of these 99 men survived."

"Bren Gunner Ernie Leggett served with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment after joining as a drummer boy at 19 in 1939. He is now 80 and living in Norwich. Only an enemy shell which almost blew him to bits, spared the infantryman the fate of his comrades as they tried to keep Hitler’s Army from reaching Dunkirk. They were cold bloodedly murdered in one of the most infamous massacres of the war.

Ernie Leggett recalls

“We went up as far as the River Dyle in the Netherlands and saw some terrible sights coming back because people were being bombed and strafed by Stuka planes.

Refugees were being killed and the towns were being flattened.

Water and fires were everywhere and the dead were lying in the street.

The Germans made lots of attacks against us on May 21, 22 and 23.

As I was a marksman on a Bren gun, I was able to cause quite a lot of havoc among them but they decimated us.

Out of my company of 120 men, I was one of only eight left by May 24. I was hit by a trench mortar and thrown up on to the roof of the cement factory where we had our positions.

I received severe wounds to my left leg and a big piece of shrapnel went in through my left buttock and out through my groin. My back was fractured and I had no feeling from the waist down.

I just lay there in a pool of blood and the others took me down and laid me in the lee of a railway line. My mates could not have done any more.

I couldn’t move my legs at all. I was crawling along the railway line – no clothes, my finger nails worn down to the bone – and a bomber appeared above me.

I could actually see the bomb doors open and a string of bombs fall. I was covered in earth three times in craters. The third time I managed to call out ‘Please, help me.’ I can’t remember any more until I felt my arms being pulled.

I recognised two drummers who had been in the band with me and another bandsman said ‘Bloody hell, it’s Ernie’. Then he said, ‘Bloody Hell, he’s had it.’

The next thing I knew I was looking up into the face of a medical officer and a Belgian nurse, who gave me a shot of morphine and I was put out.

For the next six or seven days I was travelling across Belgium and France in a hospital train and ambulances and finished up in the Dunkirk dunes.

I heard all the commotion and bombs being dropped before they got me on board a hospital ship.

Every so often the medical staff would come along and inject me with morphine which knocked me out until the next time I came around in terrible pain.

RUNNING

Our hospital ship, the St Julian, was painted brilliant white with a big red cross and couldn’t be mistaken, yet we were constantly bombed and strafed.

But if I had not been wounded I would now be in a cemetery with my mates. The seven left in my unit were transferred to Battalion headquarters in Le Paradis.

Just 99 of them held off a full SS Totenkopf Regiment but they were running out of ammo and it was useless to carry on so they had little choice but to surrender.

The first three who went out with a towel waving from a rifle were immediately shot down. The rest rushed out to cheers from the Germans and were taken prisoner.

During the afternoon of May 27th they were humiliated butted and struck. Their belonging were taken from them. They were marched along a road, turned left into a paddock and machine gunned. Only two of these 99 men survived."

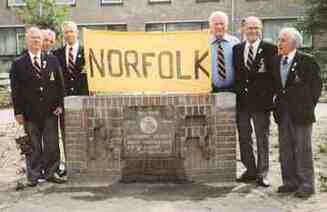

Ernie Leggett (with bugle) at one of the remembrance services for Bill O'Callaghan in Dereham. Others in the photograph include Dennis O'Callaghan, Cissie Collen, Bob Brown, Frank O'Shea, Fred Collison, Captain Walter Gilding and Stan Baines. It is likely this phot was taken around 1989.

Ernie Leggett (with bugle) at one of the remembrance services for Bill O'Callaghan in Dereham. Others in the photograph include Dennis O'Callaghan, Cissie Collen, Bob Brown, Frank O'Shea, Fred Collison, Captain Walter Gilding and Stan Baines. It is likely this phot was taken around 1989.

Comments on Private Ernie Leggett by Bob Brown

“I remember Ernie Leggett well. In Gibraltar he would wake me with reveille right outside his barrack bungalow. After the war Ernie was in the DVA (editor's note Dunkirk Veterans Association) with me so I had continued contact with him. On the pilgrimages Ernie would play reveille and last post as he did on parades all around Norfolk.

"I also remember being on a pilgrimage with Ernie at Dunkirk Cemetery where Ernie spotted the headstone of Harry Woolston and exclaimed 'we grew up together.'"

“I remember Ernie Leggett well. In Gibraltar he would wake me with reveille right outside his barrack bungalow. After the war Ernie was in the DVA (editor's note Dunkirk Veterans Association) with me so I had continued contact with him. On the pilgrimages Ernie would play reveille and last post as he did on parades all around Norfolk.

"I also remember being on a pilgrimage with Ernie at Dunkirk Cemetery where Ernie spotted the headstone of Harry Woolston and exclaimed 'we grew up together.'"

Ernie Leggett before barn modifications were made to return it to the structure of today.