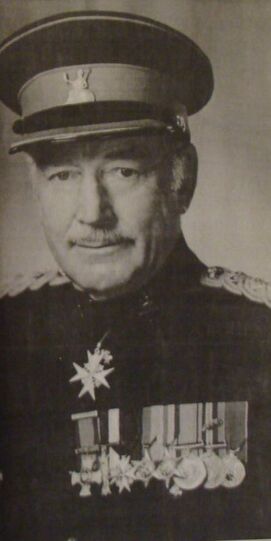

Captain Francis "Peter" Barclay M.C

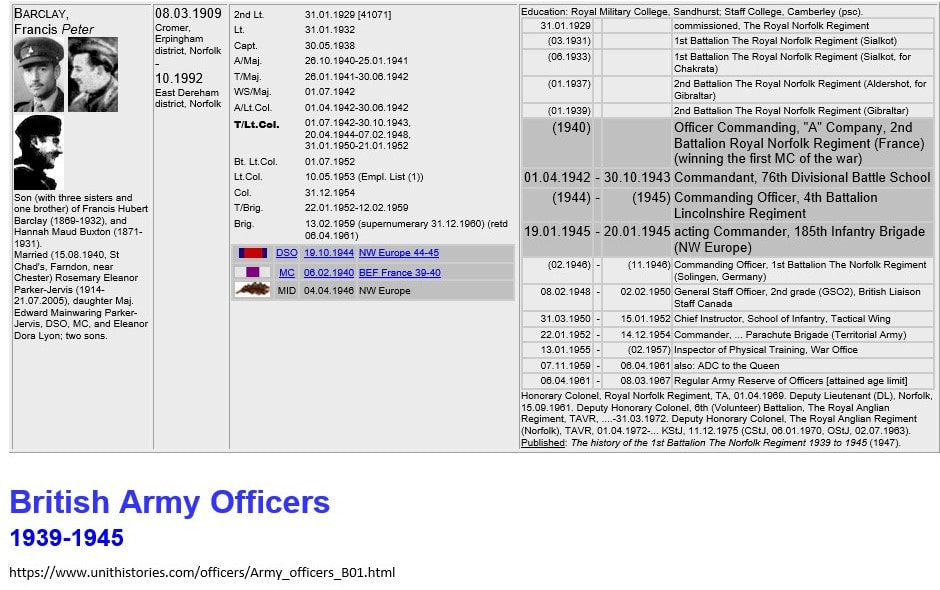

Service Record

History

Commanding Officer A Company The 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment.

Our gratitude is expressed to

By John Head

Whilst not at Le Paradis owing to wounds sustained during the Battle of the Escaut, Capt. Peter Barclay played a pivotal and heroic role in the fighting retreat of the 2nd Battalion. However, his heroics began during the period building up to the Fall Gleb (10th May 1940) known as the Phoney War.

On 20th September, 1939, when the Battalion set off from Southampton as the spearhead of the BEF Peter Barclay estimated their strength to be around 950 and described them as a ‘good fighting machine and well trained.’

On 3/4th January, during the period known as the Phoney War, Capt. Peter Barclay was involved in one of two successful patrols.

Regimental History recounts a patrol of three led by Lieutenant Patrick Everitt ‘penetrated through the enemy front and across the border into Germany, being the first time a British patrol had actually crossed the frontier during the war. It returned without being brought to action and with much valuable information’.

Captain Peter Barclay led the other patrol consisting of his company’s second in command, Second Lieutenant Murray Brown, Lance Corporal H.M. Davis and two others. Their orders were to gather intelligence on the German positions behind the barbed-wire entanglement in front of the railway station at the village of Waldwisse. A prisoner was also wanted for identification purposes.

The patrol took an hour and a half to reach the German line which appeared to be deserted. Occasionally stopping to cut wire they moved deep into enemy territory gathering much valuable information regarding the enemy dispositions. Having come across a house that appeared to be occupied they left Second Lieutenant Murray Brown on the embankment to organise cover whilst Barclay and Lance Corporal Davis went in to investigate.

They crept down into the basement room but found nobody when a sudden explosion flattened Barclay.

A grenade had landed between his legs but only damaged his boots. A firefight ensued and Barclay escaped with his patrol but lost touch with the covering officer Murray Brown where a rendezvous had been agreed. Barclay withdrew his patrol without loss despite enemy bombing and small arms fire at close range. Whilst Murray Brown had failed to appear he finally managed to get back safely on his own.

Although Barclay got a roasting from his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Hayes, Brigadier Warren, in charge of 4th Brigade was exceptionally pleased with Barclay’s exploits.

News of Barclay’s heroics on the Saar front reached the British public and in an editorial published on Saturday 13th January 1940, the Eastern Daily Press recorded:

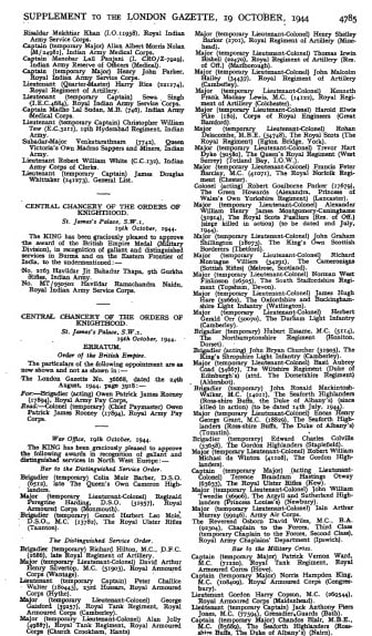

The greatest honour has fallen to the Royal Norfolk Regiment in providing the first two British soldiers to receive decorations for bravery in the field of this war. For his conspicuous gallantry, coolness and resource Captain F.P. Barclay has received from Lord Gort the Military Cross, and Corporal H. Davis, who shared his hazardous adventure, had been awarded the Military Medal. The circumstances in which they won their decorations were dangerous in the extreme. Captain Barclay had taken a patrol far behind the German lines, and in their quest for information and prisoners they searched a house in the cellars in which the enemy soldiers were hiding. Later they were attacked with grenades and rifle fire and though they became separated from the rest of their patrol they managed to return to their lines unhurt. Norfolk, no less than the regiment whose proud traditions they have so splendidly upheld, will be proud of these men and congratulate them on their honour and escape. This is the first mention that has been made of the Royal Norfolk Regiment in France since the war began. It could not have been made in finer terms.

The remainder of the patrol was mentioned in dispatches.

Sadly, the following evening Lieutenant Patrick Everitt died of wounds leading another patrol out to gather intelligence. He was the son of Sir Clement Everitt Kt and Lady Everitt (nee Croxeter) of Sheringham Norfolk and was buried by the Germans with full military honours in Rheinberg War Cemetery Germany. He was the first officer of the BEF to be killed in action.

On 5th May 1940 – Captain Peter Barclay was company commander of A Company 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment.

Whilst on the Dyle line 11/12th May, Barclay was to take the outpost position on the eastern (enemy) side of the River Dyle, whilst the rest of the Battalion remained on the western side. His orders were, in his own succinct words: ‘Give ‘em a bloody nose, old boy, and then pull out’

If we looked at the whole retreat of 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment from the Dyle line to Le Paradis this succinct order remained steadfast. The Battalion never wavered from it which was testimony to Capt. Peter Barclay’s leadership.

Barclay’s task was initially to cover the main road leading to the bridge which crossed the Dyle. His front was about 600 yards looking out across open countryside which gave him good view of anything approaching. He was hidden in the grounds of a small chateau where A Company ‘dug in’ having a very good field of fire.

With the German advance Barclay’s men watched the retreat of the Belgian army and a flood of refugees.’

At midday on the 12th 2/Norfolks moved to new positions above Wavre in the rear of Bois de Beaumont where they could hear the German advance.

During the night of 13/14 May all outposts were withdrawn and Barclay’s A Company made their way back to the Battalions new reserve positions west of the River Dyle covering the bridge blowing party after they crossed over the river. From his outpost Barclay had successfully surprised the enemy vanguard by taking out several motor cycle combinations fitted with machine guns before coming under heavy mortar and artillery fire.

The enemy was now on the far bank of the River Dyle and on the 15th May the Battalion had completed the digging and tactical wiring of their defensive position when it was reported that the village of Bierges north west of Wavre was in enemy hands leaving the Battalion exposed. A and C company were called up to deal with the situation. C to cover the rear of the village and support A if necessary.

Barclay was sent for by the Commanding Officer Lt. Col. de Wilton who appeared to Barclay to be ‘in a state’ advising the Germans had crossed the river to the right although, to Barclay, little was known about it. Nevertheless, de Wilton ordered Barclay to retake the village of Bierges and, although hesitant, Barclay planned his attack which would commence with Artillery shelling aided by machine-guns from 2/Manchesters and mortars from both flanks. The attack lasted ten minutes as A Company leap-frogged forward until 150 yards away from the village when a planned bayonet charge would be the final assault.

To everyone’s surprise there was no retaliatory fire. A carrier with Lt. Col. Money Commanding Officer of the Royal Scots appeared from the village confirming the village was already in the hands of the Royal Scots and that Barclay was to stay with them until the issue had been sorted. It was clear that Lt Col de Wilton had misjudged the situation. Barclay’s assessment was that his Commanding Officer was actually ‘in a very high state of excitement and wrought nervousness (and) imagined this thing had happened’. Such was his mental state that he ‘was convinced the village had been captured and it was Reserve company’s job to retake it.’

Orders were now received to retire from the Dyle line to a new position on the River Lasne in the neighbourhood of Overyssche therefore the good defensive positions were abandoned at the Wavre sector as the Dyle front was evacuated.

The Brigade was now deployed on a three battalion fronts: Lancashire Fusiliers on the left, Royal Norfolks in the centre and Royal Scots on the right. Battalion HQ was established in a chateau near Maliezen ‘B’ ‘C’ and ‘D’ were the forwards companies whilst Capt. Barclay’s ‘A’ was in reserve.

Toward the evening of 16th, the Battalion received orders to fall back from The River Lasne to the Brussels-Charleroi Canal and reached their positions at Loth at 0800 hours the following morning then hurriedly made their way for Ribstraat near Grammont on the River Dendre which was crossed at 1900 hour in the evening. It was said by Pte Ernie Leggett that A company marched whilst asleep. Early on the morning of 18th de Wilton’s leadership of the Battalion came to an end and he was evacuated. As much as Barclay liked him he was critical of his appointment to command the Battalion – stating that ‘he was a wonderful officer on the training side and it was a tragedy that he cracked up but it could have been avoided if it was noted he was evacuated from supposed shell-shock in the First World War’. He was given various staff jobs but he was never the same man again as what happened to him worked on his conscious forever and he died not long after the war.

Major Nicolas Charlton took over command with Major Lisle Ryder promoted Second in Command. Capt. Long was appointed OC HQ Company.

Barclay said the records in the War Diary stated the company commanders were such a good team knowing each other’s form so well and knew how to cope with predictable situations.

Reconnaissance of defensive positions along the west bank of the River Dendre commenced at approx. 0600 hrs on 18th May. By 0900 hrs the Battalion had taken up their position south of Grammont whilst Battalion HQ remained at Ribstraat. With the bridges destroyed the enemy regrouped the other side of the river but with darkness falling they began to cross in dinghies and barges. However, the Battalion received orders to at 0100 hrs on 19th May for a further withdrawal to Froidment on the River Escaut.

Barclay explained:

‘We never ever carried out a withdrawal in contact. If we thought it was likely, we patrolled very offensively against the enemy positions before we pulled out; it gave them something to think about and then extricated ourselves without fear of interference. This in fact, occurred every time, we were never once molested in our withdrawal which I was thankful about because nearly always I was a rear-guard company and you had a horrible sort of feeling of getting one up the pants as you were coming out. But it never came to that.’

Between the objective of Froidment, lay the town of Tournai which was being bombed in the air and demolished as the Battalion approached which led to chaos and confusion in keeping the Battalion together. By the end of the day Froidment had been reached and with all troops under cover in woods with slit trenches being dug against an attack.

The next morning reconnaissance of the river took place and, after a fruitless search for fifth columnists, the Battalion moved forward from St Maur to the banks of the River Escaut. By midnight the Brigade was in position with all three Battalions in line: Royal Scots on the right, Lancashire Fusiliers in the middle and the Royal Norfolks on the left.

The seven British Divisions were defending a line of 32 miles with defensive depth being sacrificed for concentration on the river line itself - each battalion responsible for about a mile of winding river bank. Therefore, a frontage by an individual company could be between 700 - 800 yards. Peter Barclay remarked that this was a lot for a company in close country.

Barclay’s A company had taken over positions near Cherq from the Royal Berkshire Regiment and the men were proceeding to strengthen them.

Barclay observed ‘There were buildings on our side of the canal and there was a plantation on the enemy side so we had to have a pretty effective system of cross fire. My company preparations were completed during the hours of darkness. I went round and they were jolly well camouflaged too. Some were in the cellars with sort of loopholes just under the roofs, one lot hiding behind a garden wall with loopholes; well concealed positions which gave good coverage of the frontage I was responsible for’.

One building occupied by a section from Barclay’s company was a former cement factory.

‘A’ company was in the centre of the Battalion line with ‘D’ to the left, ‘B’ to the right and ‘C’ in reserve. Battalion HQ was established in a Chateau in Calonne.

There were, however, blind spots in the defences and the River Escaut was becoming less of an obstacle with water levels dropping at places less than three feet deep. Brigadier Warren commander of 4th Infantry Brigade was informed that it was the BEF’s intention to ‘stand and fight’ at this position.

In the early hours of 21st May Capt. Barclay was hunting rabbits in the chateau grounds where some of his company’s positions were located thinking he would get in a bit of sport before the fun began. However, after an hour and a half, shelling started along the river line generally.

The German attack commenced at 0440 hrs; the SOS was fired by Company B on the right of 2/Norfolks and artillery fire was immediately brought to bear.

Battalion HQ at Calonne was hit. Major Carlton was wounded and Major Ryder took command.

When the German appeared on the opposite bank Capt. Barclay decided not to engage them immediately and ordered his men to hold their fire until they heard his hunting horn.

A German officer and senior warrant officers stood in full view studying a map. 2/Norfolks were well concealed and waited while the German cut down young trees from the plantation to make hurdles for crossing the river They allowed the Germans to position the trees across the remains of a demolished bridge and start to scramble over. When about 25 were across and others were grouping, Barclay blew his hunting horn and his men open fired.

…’with consummate accuracy and disposed of all the enemy personnel on our side of the canal and also the ones on the far side…..then, of course, we came in for an inordinate amount of shelling and mortar fire. After the initial burst of fire and their enormous casualties they knew pretty well where we were. Their mortar fire was very accurate. Not so long after, I was wounded in the guts, back and arm. I had a field dressing put on each of my wounds.'

As there had been several casualties, no stretcher- bearers were immediately available for Barclay, but his ever-resourceful batman:

‘with great presence of mind, ripped a door off it’s hinges and in spite of my order to the contrary, tied me on to this door. In fact, had he not done this I probably wouldn’t be here to tell the tale. But there I was tied to this door and I thought: ‘Right you’ve not only got my weight to contend with but you’ve got the door as well’ And so, of course, that took four people.

Elements of the enemy from the 2nd Battalion Infantry Regiment 54 eventually succeeded in gaining a foothold forcing the line between the Norfolks and the Lancashire Fusiliers. ‘B’ Company’s positions were overrun exposing ‘A’ Company’s right flank.

‘Suddenly’ said Barclay, who was still commanding from his makeshift stretcher, ‘we were fired at by Germans from our side of the canal.'

To deal with this dangerous development, Company Sergeant Major George Gristock assembled a party of eight men, including a company clerk and a wireless operator, from Company HQ.

According to the Regimental History.

He realised that an enemy machine-gun had been brought up to a position where it was causing severe casualties in the company and went forward by himself, with one man as connecting file, to try and put it out of action. He himself came under heavy machine-gun fire form another positions and was severely wounded in both legs (his right knee was badly smashed). He dragged himself forwards top within twenty yards of the enemy gun and, by well-directed fire, killed the crew of four and put the gun out of action. He then made his way back to the company flank and directed the defence, refusing to be evacuated until contact with the battalion on the right had been made and the line restored.

At this point ‘C’ Company arrived and consolidated the right flank, but they now had to take over the position formerly occupied by ‘B’ Company which left the Battalion without reserve.

Later, Barclay and Gristock, together with Capt. Allen of ‘B’ Company were evacuated.

Gristock succumbed to his wounds in Brighton Hospital following which he was awarded a posthumous VC primarily assisted by the account given by Capt. Barclay from his hospital bed.

This ended Captain Peter Barclay’s involvement in the heroic fighting retreat of the 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment – however his words ‘Give ‘em a bloody nose, old boy, and then pull out’ were adhered to by the Battalion to the bitter end.

Our gratitude is expressed to

- Mrs Debbi Lane, widow of the author Richard Lane, who has kindly allowed us to use the research information contained in his book ‘Last Stand at Le Paradis’ in memory of him.

- The Long family for the use of Capt. Charles Long’s War Diary.

- Journalist and historian Steve Snelling.

- The Eastern Daily Press and Archant Ltd.

By John Head

Whilst not at Le Paradis owing to wounds sustained during the Battle of the Escaut, Capt. Peter Barclay played a pivotal and heroic role in the fighting retreat of the 2nd Battalion. However, his heroics began during the period building up to the Fall Gleb (10th May 1940) known as the Phoney War.

On 20th September, 1939, when the Battalion set off from Southampton as the spearhead of the BEF Peter Barclay estimated their strength to be around 950 and described them as a ‘good fighting machine and well trained.’

On 3/4th January, during the period known as the Phoney War, Capt. Peter Barclay was involved in one of two successful patrols.

Regimental History recounts a patrol of three led by Lieutenant Patrick Everitt ‘penetrated through the enemy front and across the border into Germany, being the first time a British patrol had actually crossed the frontier during the war. It returned without being brought to action and with much valuable information’.

Captain Peter Barclay led the other patrol consisting of his company’s second in command, Second Lieutenant Murray Brown, Lance Corporal H.M. Davis and two others. Their orders were to gather intelligence on the German positions behind the barbed-wire entanglement in front of the railway station at the village of Waldwisse. A prisoner was also wanted for identification purposes.

The patrol took an hour and a half to reach the German line which appeared to be deserted. Occasionally stopping to cut wire they moved deep into enemy territory gathering much valuable information regarding the enemy dispositions. Having come across a house that appeared to be occupied they left Second Lieutenant Murray Brown on the embankment to organise cover whilst Barclay and Lance Corporal Davis went in to investigate.

They crept down into the basement room but found nobody when a sudden explosion flattened Barclay.

A grenade had landed between his legs but only damaged his boots. A firefight ensued and Barclay escaped with his patrol but lost touch with the covering officer Murray Brown where a rendezvous had been agreed. Barclay withdrew his patrol without loss despite enemy bombing and small arms fire at close range. Whilst Murray Brown had failed to appear he finally managed to get back safely on his own.

Although Barclay got a roasting from his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Hayes, Brigadier Warren, in charge of 4th Brigade was exceptionally pleased with Barclay’s exploits.

News of Barclay’s heroics on the Saar front reached the British public and in an editorial published on Saturday 13th January 1940, the Eastern Daily Press recorded:

The greatest honour has fallen to the Royal Norfolk Regiment in providing the first two British soldiers to receive decorations for bravery in the field of this war. For his conspicuous gallantry, coolness and resource Captain F.P. Barclay has received from Lord Gort the Military Cross, and Corporal H. Davis, who shared his hazardous adventure, had been awarded the Military Medal. The circumstances in which they won their decorations were dangerous in the extreme. Captain Barclay had taken a patrol far behind the German lines, and in their quest for information and prisoners they searched a house in the cellars in which the enemy soldiers were hiding. Later they were attacked with grenades and rifle fire and though they became separated from the rest of their patrol they managed to return to their lines unhurt. Norfolk, no less than the regiment whose proud traditions they have so splendidly upheld, will be proud of these men and congratulate them on their honour and escape. This is the first mention that has been made of the Royal Norfolk Regiment in France since the war began. It could not have been made in finer terms.

The remainder of the patrol was mentioned in dispatches.

Sadly, the following evening Lieutenant Patrick Everitt died of wounds leading another patrol out to gather intelligence. He was the son of Sir Clement Everitt Kt and Lady Everitt (nee Croxeter) of Sheringham Norfolk and was buried by the Germans with full military honours in Rheinberg War Cemetery Germany. He was the first officer of the BEF to be killed in action.

On 5th May 1940 – Captain Peter Barclay was company commander of A Company 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment.

Whilst on the Dyle line 11/12th May, Barclay was to take the outpost position on the eastern (enemy) side of the River Dyle, whilst the rest of the Battalion remained on the western side. His orders were, in his own succinct words: ‘Give ‘em a bloody nose, old boy, and then pull out’

If we looked at the whole retreat of 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment from the Dyle line to Le Paradis this succinct order remained steadfast. The Battalion never wavered from it which was testimony to Capt. Peter Barclay’s leadership.

Barclay’s task was initially to cover the main road leading to the bridge which crossed the Dyle. His front was about 600 yards looking out across open countryside which gave him good view of anything approaching. He was hidden in the grounds of a small chateau where A Company ‘dug in’ having a very good field of fire.

With the German advance Barclay’s men watched the retreat of the Belgian army and a flood of refugees.’

At midday on the 12th 2/Norfolks moved to new positions above Wavre in the rear of Bois de Beaumont where they could hear the German advance.

During the night of 13/14 May all outposts were withdrawn and Barclay’s A Company made their way back to the Battalions new reserve positions west of the River Dyle covering the bridge blowing party after they crossed over the river. From his outpost Barclay had successfully surprised the enemy vanguard by taking out several motor cycle combinations fitted with machine guns before coming under heavy mortar and artillery fire.

The enemy was now on the far bank of the River Dyle and on the 15th May the Battalion had completed the digging and tactical wiring of their defensive position when it was reported that the village of Bierges north west of Wavre was in enemy hands leaving the Battalion exposed. A and C company were called up to deal with the situation. C to cover the rear of the village and support A if necessary.

Barclay was sent for by the Commanding Officer Lt. Col. de Wilton who appeared to Barclay to be ‘in a state’ advising the Germans had crossed the river to the right although, to Barclay, little was known about it. Nevertheless, de Wilton ordered Barclay to retake the village of Bierges and, although hesitant, Barclay planned his attack which would commence with Artillery shelling aided by machine-guns from 2/Manchesters and mortars from both flanks. The attack lasted ten minutes as A Company leap-frogged forward until 150 yards away from the village when a planned bayonet charge would be the final assault.

To everyone’s surprise there was no retaliatory fire. A carrier with Lt. Col. Money Commanding Officer of the Royal Scots appeared from the village confirming the village was already in the hands of the Royal Scots and that Barclay was to stay with them until the issue had been sorted. It was clear that Lt Col de Wilton had misjudged the situation. Barclay’s assessment was that his Commanding Officer was actually ‘in a very high state of excitement and wrought nervousness (and) imagined this thing had happened’. Such was his mental state that he ‘was convinced the village had been captured and it was Reserve company’s job to retake it.’

Orders were now received to retire from the Dyle line to a new position on the River Lasne in the neighbourhood of Overyssche therefore the good defensive positions were abandoned at the Wavre sector as the Dyle front was evacuated.

The Brigade was now deployed on a three battalion fronts: Lancashire Fusiliers on the left, Royal Norfolks in the centre and Royal Scots on the right. Battalion HQ was established in a chateau near Maliezen ‘B’ ‘C’ and ‘D’ were the forwards companies whilst Capt. Barclay’s ‘A’ was in reserve.

Toward the evening of 16th, the Battalion received orders to fall back from The River Lasne to the Brussels-Charleroi Canal and reached their positions at Loth at 0800 hours the following morning then hurriedly made their way for Ribstraat near Grammont on the River Dendre which was crossed at 1900 hour in the evening. It was said by Pte Ernie Leggett that A company marched whilst asleep. Early on the morning of 18th de Wilton’s leadership of the Battalion came to an end and he was evacuated. As much as Barclay liked him he was critical of his appointment to command the Battalion – stating that ‘he was a wonderful officer on the training side and it was a tragedy that he cracked up but it could have been avoided if it was noted he was evacuated from supposed shell-shock in the First World War’. He was given various staff jobs but he was never the same man again as what happened to him worked on his conscious forever and he died not long after the war.

Major Nicolas Charlton took over command with Major Lisle Ryder promoted Second in Command. Capt. Long was appointed OC HQ Company.

Barclay said the records in the War Diary stated the company commanders were such a good team knowing each other’s form so well and knew how to cope with predictable situations.

Reconnaissance of defensive positions along the west bank of the River Dendre commenced at approx. 0600 hrs on 18th May. By 0900 hrs the Battalion had taken up their position south of Grammont whilst Battalion HQ remained at Ribstraat. With the bridges destroyed the enemy regrouped the other side of the river but with darkness falling they began to cross in dinghies and barges. However, the Battalion received orders to at 0100 hrs on 19th May for a further withdrawal to Froidment on the River Escaut.

Barclay explained:

‘We never ever carried out a withdrawal in contact. If we thought it was likely, we patrolled very offensively against the enemy positions before we pulled out; it gave them something to think about and then extricated ourselves without fear of interference. This in fact, occurred every time, we were never once molested in our withdrawal which I was thankful about because nearly always I was a rear-guard company and you had a horrible sort of feeling of getting one up the pants as you were coming out. But it never came to that.’

Between the objective of Froidment, lay the town of Tournai which was being bombed in the air and demolished as the Battalion approached which led to chaos and confusion in keeping the Battalion together. By the end of the day Froidment had been reached and with all troops under cover in woods with slit trenches being dug against an attack.

The next morning reconnaissance of the river took place and, after a fruitless search for fifth columnists, the Battalion moved forward from St Maur to the banks of the River Escaut. By midnight the Brigade was in position with all three Battalions in line: Royal Scots on the right, Lancashire Fusiliers in the middle and the Royal Norfolks on the left.

The seven British Divisions were defending a line of 32 miles with defensive depth being sacrificed for concentration on the river line itself - each battalion responsible for about a mile of winding river bank. Therefore, a frontage by an individual company could be between 700 - 800 yards. Peter Barclay remarked that this was a lot for a company in close country.

Barclay’s A company had taken over positions near Cherq from the Royal Berkshire Regiment and the men were proceeding to strengthen them.

Barclay observed ‘There were buildings on our side of the canal and there was a plantation on the enemy side so we had to have a pretty effective system of cross fire. My company preparations were completed during the hours of darkness. I went round and they were jolly well camouflaged too. Some were in the cellars with sort of loopholes just under the roofs, one lot hiding behind a garden wall with loopholes; well concealed positions which gave good coverage of the frontage I was responsible for’.

One building occupied by a section from Barclay’s company was a former cement factory.

‘A’ company was in the centre of the Battalion line with ‘D’ to the left, ‘B’ to the right and ‘C’ in reserve. Battalion HQ was established in a Chateau in Calonne.

There were, however, blind spots in the defences and the River Escaut was becoming less of an obstacle with water levels dropping at places less than three feet deep. Brigadier Warren commander of 4th Infantry Brigade was informed that it was the BEF’s intention to ‘stand and fight’ at this position.

In the early hours of 21st May Capt. Barclay was hunting rabbits in the chateau grounds where some of his company’s positions were located thinking he would get in a bit of sport before the fun began. However, after an hour and a half, shelling started along the river line generally.

The German attack commenced at 0440 hrs; the SOS was fired by Company B on the right of 2/Norfolks and artillery fire was immediately brought to bear.

Battalion HQ at Calonne was hit. Major Carlton was wounded and Major Ryder took command.

When the German appeared on the opposite bank Capt. Barclay decided not to engage them immediately and ordered his men to hold their fire until they heard his hunting horn.

A German officer and senior warrant officers stood in full view studying a map. 2/Norfolks were well concealed and waited while the German cut down young trees from the plantation to make hurdles for crossing the river They allowed the Germans to position the trees across the remains of a demolished bridge and start to scramble over. When about 25 were across and others were grouping, Barclay blew his hunting horn and his men open fired.

…’with consummate accuracy and disposed of all the enemy personnel on our side of the canal and also the ones on the far side…..then, of course, we came in for an inordinate amount of shelling and mortar fire. After the initial burst of fire and their enormous casualties they knew pretty well where we were. Their mortar fire was very accurate. Not so long after, I was wounded in the guts, back and arm. I had a field dressing put on each of my wounds.'

As there had been several casualties, no stretcher- bearers were immediately available for Barclay, but his ever-resourceful batman:

‘with great presence of mind, ripped a door off it’s hinges and in spite of my order to the contrary, tied me on to this door. In fact, had he not done this I probably wouldn’t be here to tell the tale. But there I was tied to this door and I thought: ‘Right you’ve not only got my weight to contend with but you’ve got the door as well’ And so, of course, that took four people.

Elements of the enemy from the 2nd Battalion Infantry Regiment 54 eventually succeeded in gaining a foothold forcing the line between the Norfolks and the Lancashire Fusiliers. ‘B’ Company’s positions were overrun exposing ‘A’ Company’s right flank.

‘Suddenly’ said Barclay, who was still commanding from his makeshift stretcher, ‘we were fired at by Germans from our side of the canal.'

To deal with this dangerous development, Company Sergeant Major George Gristock assembled a party of eight men, including a company clerk and a wireless operator, from Company HQ.

According to the Regimental History.

He realised that an enemy machine-gun had been brought up to a position where it was causing severe casualties in the company and went forward by himself, with one man as connecting file, to try and put it out of action. He himself came under heavy machine-gun fire form another positions and was severely wounded in both legs (his right knee was badly smashed). He dragged himself forwards top within twenty yards of the enemy gun and, by well-directed fire, killed the crew of four and put the gun out of action. He then made his way back to the company flank and directed the defence, refusing to be evacuated until contact with the battalion on the right had been made and the line restored.

At this point ‘C’ Company arrived and consolidated the right flank, but they now had to take over the position formerly occupied by ‘B’ Company which left the Battalion without reserve.

Later, Barclay and Gristock, together with Capt. Allen of ‘B’ Company were evacuated.

Gristock succumbed to his wounds in Brighton Hospital following which he was awarded a posthumous VC primarily assisted by the account given by Capt. Barclay from his hospital bed.

This ended Captain Peter Barclay’s involvement in the heroic fighting retreat of the 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment – however his words ‘Give ‘em a bloody nose, old boy, and then pull out’ were adhered to by the Battalion to the bitter end.

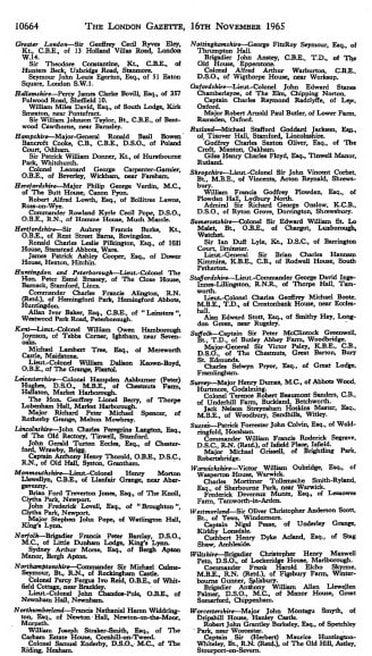

Above is an article about Peter Barclay by historian and journalist Steve Snelling. It appeared in the Eastern Daily Press newspaper of November 13th, 1992. Below is a transcript of that article.

In respect of this publication, our gratitude is expressed to

Exploits of a Regimental Hero

Today, old soldiers and civic dignitaries will attend a memorial service in Norwich Cathedral to salute the memory of Brigadier Peter Barclay, DSO, MC one of the Royal Norfolk Regiment’s most distinguished officers, who died last month.

A former Deputy Lieutenant of Norfolk, he came to embody the very soul of the regiment he served so faithfully in peace and war.

STEVE SNELLING, who interviewed Brig. Barclay before his death pays tribute to him and recounts the story of one of his most memorable exploits.

A full moon cast eerie shadows across the snow-shrouded expanse of no-man’s land as a small party of British soldiers picked their way across the frozen earth.

Their orders were to explore the buildings clustered close to the deserted railway station of Waldwisse in the Saarland. For this small undistinguished village on the borders of France and Germany had become trapped by geography in the frontline of the second great conflict to engulf mainland Europe in the space of 25 years.

But this, as far as the soldiers on the western front were concerned, was a war like no other, a war of bewildering inactivity.

For four months, the opposing armies straddling the west German border had sat glowering at one another behind barbed wire entanglements and sand-bagged trenches.

But now on the night of January 3/4, 1940, in the midst of the coldest winter for 20 years, a patrol of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment was venturing out on a mission that would lead to one of the so-called Phoney War’s most memorable flashpoints.

In command of the party was a 30-year-old company commander who, over the course of the next five years, would become one of the regiment’s most distinguished frontline soldiers.

Peter Barclay, a veteran of ten years peace-time soldiering, had already deservedly and almost effortlessly acquired a reputation for dynamic leadership and forthright behaviour.

No stranger to controversy, he combined to a rare degree an inspiring mixture of charismatic, if sometimes eccentric, charm with a capacity for sheer bloody-mindedness which bordered at times on insubordination.

The war was only a few weeks old when he clashed with his commanding officer over the appointment of a sergeant major to one of his platoons. Barclay wanted a hard-drinking former cavalry man called George Gristock.

Years later Barclay remembered “I had a hell of a row with him. I said I wouldn’t change my mind and the CO didn’t speak to me for a couple of days.” But he got his way, and months later, during the bitter fighting near the River Escaut, his faith was repaid in full when Gristock, by then a Company Sergeant Major, showed heroism later recognised by the posthumous award of the Regiment’s first Victoria Cross of the second world war.

Not for nothing did Field Marshal Montgomery refer to Peter Barclay as “my obstinate friend”.

But there was much more to Barclay than stubborn defiance and the action at Waldwisse which first brought him to the attention of his senior officers reflected many of his endearing and enduring characteristics – daring leadership, high spirited good humour in most perilous circumstances, great good fortune and no little controversy.

Many years later, on another winter’s night he recounted the story behind one of the war’s most publicised minor actions.

As sparks flew from the logs burning in the fireplace at Little Dunham Lodge, he recalled: “we went down to the railway embankment between the two lines, and through God knows how many yards of barbed wire towards the German positions.”

Venturing deep into enemy lines, deeper than most previous reconnaissance, Barclay’s patrol gathered a wealth of information about the German positions. But he was not content with this. He wanted to bring back a German prisoner.

“It was terribly exciting. I had my company second in command and I put him on the embankment to cover Cpl. Davies and myself while we investigated one of the houses.

“We knew they were either in there or recently in there. There were boot prints in the snow and smoke coming out of the chimney.

“We crept in, went down to the lower floor into a basement room. There was a glowing fire but there weren’t any bloody Germans there. And then I saw this lovely carved wooden bear being used as a door stopper and I thought I’ll jolly well take that home when suddenly there was a frightful explosion and I fell on my face.

“A grenade had landed between my legs, made rather a nasty mess of my boots but hadn’t affected me in any other way at all.

“Then of course there was absolutely all hell let loose. Up went the Verey lights. German fire from absolutely point-blank range all round us and I couldn’t get my prisoner. In fact, we had a hell of a job to get out.

“I picked up the rest of our party except our second in command. We waited for him as long as we dare, then I took the rest of the chaps back.

“When I got home I reported to my colonel and all I got was a blistering rocket for having taken my company second in command without his authority. My brigadier came along the next day and he was frightfully pleased about this and he patted mem on the back and said ‘You’ve done a damned fine show. It’s the best bit of news that’s happened to the BEF since we came out here’

“There was my colonel listening and the French general commanding the artillery was in the party too. He said ‘Mon brave capitaine’ and embraced me on both cheeks. My colonel said ‘If you don’t deserve a decoration for anything else, you do for the way you accepted those embraces’”

The action, so typical of him, resulted in the award of the first Military Cross of the war. The army had its first hero, Peter Barclay had taken a big stride to regimental fame.

In respect of this publication, our gratitude is expressed to

- Steve Snelling

- The Eastern Daily Press and Archant Ltd

Exploits of a Regimental Hero

Today, old soldiers and civic dignitaries will attend a memorial service in Norwich Cathedral to salute the memory of Brigadier Peter Barclay, DSO, MC one of the Royal Norfolk Regiment’s most distinguished officers, who died last month.

A former Deputy Lieutenant of Norfolk, he came to embody the very soul of the regiment he served so faithfully in peace and war.

STEVE SNELLING, who interviewed Brig. Barclay before his death pays tribute to him and recounts the story of one of his most memorable exploits.

A full moon cast eerie shadows across the snow-shrouded expanse of no-man’s land as a small party of British soldiers picked their way across the frozen earth.

Their orders were to explore the buildings clustered close to the deserted railway station of Waldwisse in the Saarland. For this small undistinguished village on the borders of France and Germany had become trapped by geography in the frontline of the second great conflict to engulf mainland Europe in the space of 25 years.

But this, as far as the soldiers on the western front were concerned, was a war like no other, a war of bewildering inactivity.

For four months, the opposing armies straddling the west German border had sat glowering at one another behind barbed wire entanglements and sand-bagged trenches.

But now on the night of January 3/4, 1940, in the midst of the coldest winter for 20 years, a patrol of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment was venturing out on a mission that would lead to one of the so-called Phoney War’s most memorable flashpoints.

In command of the party was a 30-year-old company commander who, over the course of the next five years, would become one of the regiment’s most distinguished frontline soldiers.

Peter Barclay, a veteran of ten years peace-time soldiering, had already deservedly and almost effortlessly acquired a reputation for dynamic leadership and forthright behaviour.

No stranger to controversy, he combined to a rare degree an inspiring mixture of charismatic, if sometimes eccentric, charm with a capacity for sheer bloody-mindedness which bordered at times on insubordination.

The war was only a few weeks old when he clashed with his commanding officer over the appointment of a sergeant major to one of his platoons. Barclay wanted a hard-drinking former cavalry man called George Gristock.

Years later Barclay remembered “I had a hell of a row with him. I said I wouldn’t change my mind and the CO didn’t speak to me for a couple of days.” But he got his way, and months later, during the bitter fighting near the River Escaut, his faith was repaid in full when Gristock, by then a Company Sergeant Major, showed heroism later recognised by the posthumous award of the Regiment’s first Victoria Cross of the second world war.

Not for nothing did Field Marshal Montgomery refer to Peter Barclay as “my obstinate friend”.

But there was much more to Barclay than stubborn defiance and the action at Waldwisse which first brought him to the attention of his senior officers reflected many of his endearing and enduring characteristics – daring leadership, high spirited good humour in most perilous circumstances, great good fortune and no little controversy.

Many years later, on another winter’s night he recounted the story behind one of the war’s most publicised minor actions.

As sparks flew from the logs burning in the fireplace at Little Dunham Lodge, he recalled: “we went down to the railway embankment between the two lines, and through God knows how many yards of barbed wire towards the German positions.”

Venturing deep into enemy lines, deeper than most previous reconnaissance, Barclay’s patrol gathered a wealth of information about the German positions. But he was not content with this. He wanted to bring back a German prisoner.

“It was terribly exciting. I had my company second in command and I put him on the embankment to cover Cpl. Davies and myself while we investigated one of the houses.

“We knew they were either in there or recently in there. There were boot prints in the snow and smoke coming out of the chimney.

“We crept in, went down to the lower floor into a basement room. There was a glowing fire but there weren’t any bloody Germans there. And then I saw this lovely carved wooden bear being used as a door stopper and I thought I’ll jolly well take that home when suddenly there was a frightful explosion and I fell on my face.

“A grenade had landed between my legs, made rather a nasty mess of my boots but hadn’t affected me in any other way at all.

“Then of course there was absolutely all hell let loose. Up went the Verey lights. German fire from absolutely point-blank range all round us and I couldn’t get my prisoner. In fact, we had a hell of a job to get out.

“I picked up the rest of our party except our second in command. We waited for him as long as we dare, then I took the rest of the chaps back.

“When I got home I reported to my colonel and all I got was a blistering rocket for having taken my company second in command without his authority. My brigadier came along the next day and he was frightfully pleased about this and he patted mem on the back and said ‘You’ve done a damned fine show. It’s the best bit of news that’s happened to the BEF since we came out here’

“There was my colonel listening and the French general commanding the artillery was in the party too. He said ‘Mon brave capitaine’ and embraced me on both cheeks. My colonel said ‘If you don’t deserve a decoration for anything else, you do for the way you accepted those embraces’”

The action, so typical of him, resulted in the award of the first Military Cross of the war. The army had its first hero, Peter Barclay had taken a big stride to regimental fame.

In Awe of Peter Barclay

We are extremely grateful to Mrs Vicky Gee for allowing us to publish her memories of Brigadier Peter Barclay DSO MC (Captain Peter Barclay MC Commanding Officer A Company 2nd Battalion Royal Norfolk Regiment River Escaut 21st May 1940)

Mrs Gee is the daughter of Major Charles Long MC (Captain Charles Long MC Adjutant at Le Paradis 27th May 1940).

After the War Major Long MC and Brigadier Barclay DSO MC remained friends.

Vicky recalls that he (Peter Barclay) was always there in her childhood and she was slightly in awe of him. He would stay with her family in Germany while visiting H.Q. in Hilden Vicky would have been 7/8 at the time.

“He was quite austere and distant to us children” said Vicky “but used to drive us to school in his beautiful Jaguar which caused quite a stir in the playground!

Nowadays children would not be interested but all the little boys loved cars in those days. He would be more relaxed with us when he did this and one time I remember him telling us about how he would take his little dog with him across to France during the war. He had a special hold-all bag for him and trained him to sit or lie depending on whether he was being carried or on the ground. He never got caught !”

Remembering with affection Vicky continued;

“Occasionally Peter’s wife would accompany him and once they stayed before and after a visit to Bavaria and brought me back a bracelet of edelweiss and a little white China horse which I had for years and loved. Another time he rode down to see my father with Colonel Crawford from Hilden camp and when they left he put me up on his horse and let me ride as far as the main road, I’ve never forgotten the thrill! I can also remember meeting him with my parents at the Royal Norfolk Show and at Point to Point meetings”

Vicky also advised that by coincidence her father’s maiden aunt Edith was governess to Peter Barclay, Polly and his other siblings when they were children. Polly Blount (as she became) often mentioned Edith when she and Vicky rode together around Cley. Polly and Colonel Blount lived at Cley Old Hall and Vicky’s parents by then, lived nearby in the East Wing of Cley Hall (the ‘new’ Hall).

Another sad coincidence which rocked the village of Cley was that Vicky’s father Major Charles Long MC and Colonel Blount both died on the same day.

Note: Peter Barclay was great uncle to James Blount (Blunt) English singer, songwriter and musician.

Mrs Gee is the daughter of Major Charles Long MC (Captain Charles Long MC Adjutant at Le Paradis 27th May 1940).

After the War Major Long MC and Brigadier Barclay DSO MC remained friends.

Vicky recalls that he (Peter Barclay) was always there in her childhood and she was slightly in awe of him. He would stay with her family in Germany while visiting H.Q. in Hilden Vicky would have been 7/8 at the time.

“He was quite austere and distant to us children” said Vicky “but used to drive us to school in his beautiful Jaguar which caused quite a stir in the playground!

Nowadays children would not be interested but all the little boys loved cars in those days. He would be more relaxed with us when he did this and one time I remember him telling us about how he would take his little dog with him across to France during the war. He had a special hold-all bag for him and trained him to sit or lie depending on whether he was being carried or on the ground. He never got caught !”

Remembering with affection Vicky continued;

“Occasionally Peter’s wife would accompany him and once they stayed before and after a visit to Bavaria and brought me back a bracelet of edelweiss and a little white China horse which I had for years and loved. Another time he rode down to see my father with Colonel Crawford from Hilden camp and when they left he put me up on his horse and let me ride as far as the main road, I’ve never forgotten the thrill! I can also remember meeting him with my parents at the Royal Norfolk Show and at Point to Point meetings”

Vicky also advised that by coincidence her father’s maiden aunt Edith was governess to Peter Barclay, Polly and his other siblings when they were children. Polly Blount (as she became) often mentioned Edith when she and Vicky rode together around Cley. Polly and Colonel Blount lived at Cley Old Hall and Vicky’s parents by then, lived nearby in the East Wing of Cley Hall (the ‘new’ Hall).

Another sad coincidence which rocked the village of Cley was that Vicky’s father Major Charles Long MC and Colonel Blount both died on the same day.

Note: Peter Barclay was great uncle to James Blount (Blunt) English singer, songwriter and musician.