Sergeant Walter Gilding

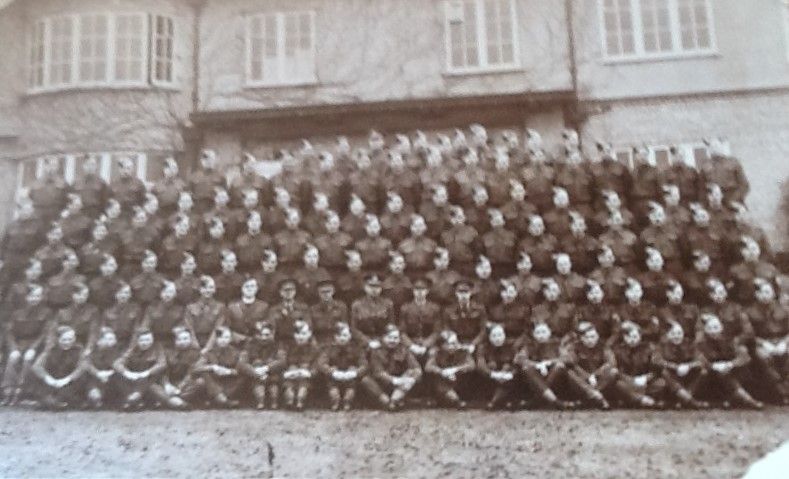

The above photograph was taken in England in 1941. Walter Gilding is in the front row on the left. Also in the photograph are: Top row (left to right) - Sgt Goodway, Sgt Collins. Front - Sgt Gilding, Second Lieutenant Whitaker and Sgt Harford.

The above photograph was taken in England in 1941. Walter Gilding is in the front row on the left. Also in the photograph are: Top row (left to right) - Sgt Goodway, Sgt Collins. Front - Sgt Gilding, Second Lieutenant Whitaker and Sgt Harford.

Company Quartermaster Sergeant Walter Gilding HQ Coy 2nd Battalion Royal Norfolk Regiment : (The man who served the last meal)

Sergeant Walter Gilding of the 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment made his way under chaotic conditions from Le Paradis to arrive at Dunkirk and was safely evacuated. He became part of the reorganised battalion which was destined for Burma and India. Sergeant Gilding’s daughter, Kay Cole, recalls one of the most noteworthy events concerning her father at Le Paradis as told by him was that, together with an officer, he served the surviving Battalion members their last meal and removed documents in case they were taken by the enemy.

The following accounts of Company Quartermaster Sergeant Walter Gilding have been taken from ‘Last Stand at Le Paradis’ with kind permission of Mrs Debbi Lane in memory of her late husband Richard Lane the author.

During a lull in the fighting as darkness gathered on 26th May, 1940, hot food was prepared and brought to Duriez Farm (Battalion HQ). Sergeant Gilding, formerly of the mortar platoon but at that time acting as Company Quartermaster Sergeant, recalled:

"I arrived at the battalion headquarters somewhere between nine and ten that evening. There was very little to be seen. Major Ryder came forward and spoke to us and said that he was glad to see us and that the food could be distributed when he could get the people off the perimeter where they were out on various defensive positions. From then on, we were feeding the lads as they were coming in in dribs and drabs. We had the signallers actually in the farmhouse itself and the riflemen were out in the buildings – the cowshed, the pigsties, even out in the little meadow around the farm – wherever they had taken up position.

"We had special containers with lids that bolted down and kept it hot. There was no sound of shots, bombs shellfire or anything. It went on like that all through the night till three o’clock in the morning. I was still there with the cook’s wagon still dishing out for the odd people that had been pulled in. Major Ryder came in and said. 'The situation seems to be getting worse’. By this time, it was just beginning to get daylight. ‘I think you’d better pack up and get back to B Echelon. But before you go report to the farmhouse where we’ve got the Company Headquarters and take some of the documents away – they’re not much use to us here!’ By the documents he meant the equipment rolls and various paperwork. It was then I heard what sounded like heavy vehicles, possibly tanks moving in the distance. Also, the first mortar bomb landed in battalion area."

Sergeant Gilding left Battalion HQ Duriez farm at 0330 on the morning of 27th May, 1940, with exploding mortar bombs giving the truck they were in a very bumpy ride.

B. Echelon was about 1½ miles north of Le Paradis at I’Epinette. When they reached the area, Sergeant Gilding found that everyone was packing up and ready to move. The Quartermaster (Lieutenant Grant) had received a message from them saying: ‘The battalion were to be staying in that position and that we were not to wait, that we were to go back to some other rendezvous.’

Sergeant Walter Gilding of the 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment made his way under chaotic conditions from Le Paradis to arrive at Dunkirk and was safely evacuated. He became part of the reorganised battalion which was destined for Burma and India. Sergeant Gilding’s daughter, Kay Cole, recalls one of the most noteworthy events concerning her father at Le Paradis as told by him was that, together with an officer, he served the surviving Battalion members their last meal and removed documents in case they were taken by the enemy.

The following accounts of Company Quartermaster Sergeant Walter Gilding have been taken from ‘Last Stand at Le Paradis’ with kind permission of Mrs Debbi Lane in memory of her late husband Richard Lane the author.

During a lull in the fighting as darkness gathered on 26th May, 1940, hot food was prepared and brought to Duriez Farm (Battalion HQ). Sergeant Gilding, formerly of the mortar platoon but at that time acting as Company Quartermaster Sergeant, recalled:

"I arrived at the battalion headquarters somewhere between nine and ten that evening. There was very little to be seen. Major Ryder came forward and spoke to us and said that he was glad to see us and that the food could be distributed when he could get the people off the perimeter where they were out on various defensive positions. From then on, we were feeding the lads as they were coming in in dribs and drabs. We had the signallers actually in the farmhouse itself and the riflemen were out in the buildings – the cowshed, the pigsties, even out in the little meadow around the farm – wherever they had taken up position.

"We had special containers with lids that bolted down and kept it hot. There was no sound of shots, bombs shellfire or anything. It went on like that all through the night till three o’clock in the morning. I was still there with the cook’s wagon still dishing out for the odd people that had been pulled in. Major Ryder came in and said. 'The situation seems to be getting worse’. By this time, it was just beginning to get daylight. ‘I think you’d better pack up and get back to B Echelon. But before you go report to the farmhouse where we’ve got the Company Headquarters and take some of the documents away – they’re not much use to us here!’ By the documents he meant the equipment rolls and various paperwork. It was then I heard what sounded like heavy vehicles, possibly tanks moving in the distance. Also, the first mortar bomb landed in battalion area."

Sergeant Gilding left Battalion HQ Duriez farm at 0330 on the morning of 27th May, 1940, with exploding mortar bombs giving the truck they were in a very bumpy ride.

B. Echelon was about 1½ miles north of Le Paradis at I’Epinette. When they reached the area, Sergeant Gilding found that everyone was packing up and ready to move. The Quartermaster (Lieutenant Grant) had received a message from them saying: ‘The battalion were to be staying in that position and that we were not to wait, that we were to go back to some other rendezvous.’

We are very grateful to Walter's daughter Kay Cole for sending the first five photographs and allowing us to publish them.

Walter is front row third from right in this photograph of the Royal Norfolk Regiment cross country team from 1936.

More About Walter Gilding

Walter Gilding was featured extensively in an article written by Jon Welch in the Eastern Daily Press of Friday July 23rd, 1999. An image of this article appears above and below is a transcript.

‘Dunkirk: spirit dies with dignity’

Dunkirk Spirit. There’s no doubt in Walter Gilding’s mind what those two words mean to him. “Reluctance to give in and supporting each other,” says Mr. Gilding, a survivor of what Winston Churchill called “a miracle of deliverance following a colossal defeat’.

In May 1940, about 330,000 members of the British Expeditionary Force were evacuated from the beaches of Northern France after being pushed back by advancing German forces.

Since then, Dunkirk has been a byword for resilience in the face of adversity and the members of the Dunkirk Veterans’ Association have done their best to keep that spirit alive since the group’s formation in 1953.

But time has proved the most ruthless enemy for veterans, and the association has seen its membership dwindle to less than a sixth of its peak.

Rather than fizzle out, however, the association has decided to bow out gracefully and the organisation will be officially wound up on June 30th next year.

Jim Horton, the general secretary, is frank about the reason for the decision. “It’s age. We are being denuded of members – people are dying off. It’s better that we should disband while the organisation is still healthy and active.” He said.

“The association has no paid staff and no offices. Everything is done voluntarily by the veterans themselves. We don’t get any assistance from the younger generation.

None of our members will be less than 80 or thereabouts in the year 2000 and it’s time we folded up with dignity and marched into history like the Old Contemptibles of the Great War.”

At one time the association had 30,000 members and 120 branches, but now numbers have dwindled to fewer than 5,000 members and 85 branches.

It was 10 years ago that the association first suggested folding in the year 2000, and the decision was finally made by the members last year. But even after the association is formally wound up, veterans will continue to meet in informal groups.

“If you are in the forces ands you see action, then the chap next to you is a very special person indeed,” says Mr. Horton, who believes the wealth of literature about Dunkirk will ensure the memory of the event lives on.

“It is vitally important that people do not forget, in the same way as they shouldn’t forget the first world war."

Norfolk has been as hotbed of support for the association as both the Norfolk Yeomanry and the 2nd Battalion Royal Norfolk Regiment were among the units evacuated at Dunkirk.

The Royal Norfolks suffered appalling losses at Le Paradis, 30 miles inland from Dunkirk. Soldiers from the regiment held out with limited supplies and ammunition in a farmhouse against a German assault before they were forced to surrender.

They were handed over to the Waffen SS who marched them to a barn deep in the countryside, lined them up and mowed them down with machine-guns, killing 99 men.

Just two men, Bert Pooley, of London, and Bill O’Callaghan, of Dereham survived, after feigning death and crawling away, badly injured. The full horror of Le Paradis did not emerge until after the war, and Pte Pooley pressed for a crimes trial, after which SS Capt. Fritz Knoechlein was executed.

When he thinks back to the massacre, Walter Gilding, 80, thanks his lucky stars. Had he not recently been promoted to acting colour-sergeant, deputising for a comrade who had been on leave, he would still have been a member of the mortar platoon holed up in the farmhouse. As it was, his section was stationed about a mile-and- a- half away and was ordered to retreat when the Germans began their attack on the farm.

Mr. Gilding, of Oulton Broad, near Lowestoft, followed orders to withdraw to Dunkirk where he assumed a final stand would be made.

“When I arrived at the beach there was a beachmaster trying to make some sort of order out of the chaos. I said ‘What’s happening? I thought we were making a stand here’ and he said ‘I’m afraid not. We’re evacuating.”

When Mr. Gilding arrived back in Dover, he could not believe the rapturous reception the returning soldiers were given. “We were being treated like heroes but we didn’t feel like heroes. We felt we had let everybody down.”

Today, Mr. Gilding is on the welfare committee of the association’s Norfolk and Norwich Branch, formed in 1963.

The branch once had 235 members but now it has 93. Branch secretary Ernie Leggett says, “I have been secretary for the last ten years and I will get the branch through to the finish.”

“The association was formed by a very small group in Leeds and it blossomed from just 30 people to 30,000. We began from nothing and gradually we are going back to nothing.”

“I feel very sad about it because we are an elite organisation, there’s no doubt about it. Although people call it a defeat, if there hadn’t been a Dunkirk there wouldn’t have been a D Day.

“We decided the best thing to do was to pack in while we were able to put one foot in front of the other – staggering but holding our heads above water.”

Mr. Leggett is also on the association’s national committee and edits the veterans’ journal. He plans to continue producing a newsletter even after the association is wound up.

‘Dunkirk: spirit dies with dignity’

Dunkirk Spirit. There’s no doubt in Walter Gilding’s mind what those two words mean to him. “Reluctance to give in and supporting each other,” says Mr. Gilding, a survivor of what Winston Churchill called “a miracle of deliverance following a colossal defeat’.

In May 1940, about 330,000 members of the British Expeditionary Force were evacuated from the beaches of Northern France after being pushed back by advancing German forces.

Since then, Dunkirk has been a byword for resilience in the face of adversity and the members of the Dunkirk Veterans’ Association have done their best to keep that spirit alive since the group’s formation in 1953.

But time has proved the most ruthless enemy for veterans, and the association has seen its membership dwindle to less than a sixth of its peak.

Rather than fizzle out, however, the association has decided to bow out gracefully and the organisation will be officially wound up on June 30th next year.

Jim Horton, the general secretary, is frank about the reason for the decision. “It’s age. We are being denuded of members – people are dying off. It’s better that we should disband while the organisation is still healthy and active.” He said.

“The association has no paid staff and no offices. Everything is done voluntarily by the veterans themselves. We don’t get any assistance from the younger generation.

None of our members will be less than 80 or thereabouts in the year 2000 and it’s time we folded up with dignity and marched into history like the Old Contemptibles of the Great War.”

At one time the association had 30,000 members and 120 branches, but now numbers have dwindled to fewer than 5,000 members and 85 branches.

It was 10 years ago that the association first suggested folding in the year 2000, and the decision was finally made by the members last year. But even after the association is formally wound up, veterans will continue to meet in informal groups.

“If you are in the forces ands you see action, then the chap next to you is a very special person indeed,” says Mr. Horton, who believes the wealth of literature about Dunkirk will ensure the memory of the event lives on.

“It is vitally important that people do not forget, in the same way as they shouldn’t forget the first world war."

Norfolk has been as hotbed of support for the association as both the Norfolk Yeomanry and the 2nd Battalion Royal Norfolk Regiment were among the units evacuated at Dunkirk.

The Royal Norfolks suffered appalling losses at Le Paradis, 30 miles inland from Dunkirk. Soldiers from the regiment held out with limited supplies and ammunition in a farmhouse against a German assault before they were forced to surrender.

They were handed over to the Waffen SS who marched them to a barn deep in the countryside, lined them up and mowed them down with machine-guns, killing 99 men.

Just two men, Bert Pooley, of London, and Bill O’Callaghan, of Dereham survived, after feigning death and crawling away, badly injured. The full horror of Le Paradis did not emerge until after the war, and Pte Pooley pressed for a crimes trial, after which SS Capt. Fritz Knoechlein was executed.

When he thinks back to the massacre, Walter Gilding, 80, thanks his lucky stars. Had he not recently been promoted to acting colour-sergeant, deputising for a comrade who had been on leave, he would still have been a member of the mortar platoon holed up in the farmhouse. As it was, his section was stationed about a mile-and- a- half away and was ordered to retreat when the Germans began their attack on the farm.

Mr. Gilding, of Oulton Broad, near Lowestoft, followed orders to withdraw to Dunkirk where he assumed a final stand would be made.

“When I arrived at the beach there was a beachmaster trying to make some sort of order out of the chaos. I said ‘What’s happening? I thought we were making a stand here’ and he said ‘I’m afraid not. We’re evacuating.”

When Mr. Gilding arrived back in Dover, he could not believe the rapturous reception the returning soldiers were given. “We were being treated like heroes but we didn’t feel like heroes. We felt we had let everybody down.”

Today, Mr. Gilding is on the welfare committee of the association’s Norfolk and Norwich Branch, formed in 1963.

The branch once had 235 members but now it has 93. Branch secretary Ernie Leggett says, “I have been secretary for the last ten years and I will get the branch through to the finish.”

“The association was formed by a very small group in Leeds and it blossomed from just 30 people to 30,000. We began from nothing and gradually we are going back to nothing.”

“I feel very sad about it because we are an elite organisation, there’s no doubt about it. Although people call it a defeat, if there hadn’t been a Dunkirk there wouldn’t have been a D Day.

“We decided the best thing to do was to pack in while we were able to put one foot in front of the other – staggering but holding our heads above water.”

Mr. Leggett is also on the association’s national committee and edits the veterans’ journal. He plans to continue producing a newsletter even after the association is wound up.